Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

THE GERMAN DEFENSE OF BERLIN, 1945

By OBERST WILHELM WILLEMER

Gleb Vasiliev. Berlin. May 1, 1945, Potsdamer Platz.

THE GERMAN DEFENSE OF BERLIN, 1945. By WILHELM WILLEMER, OBERST a.D. WITH A FOREWORD BY GENERALOBERST a.D. FRANZ HALDER

FOREWORD

by Generaloberst a.D. Franz Halder

No cohesive, over-all plan for the defense of Berlin was ever actually prepared. All that existed was the stubborn determination of Hitler to defend the capital of the Reich. Circumstances were such that he gave no thought to defending the city until it was much too late for any kind of advance planning. Thus the city's defense was characterized only by a mass of improvisations. These reveal a state of total confusion in which the pressure of the enemy, the organizational chaos on the German side, and the catastrophic shortage of human and material resources for the defense combined with disastrous effect.

The author describes these conditions in a clear, accurate report which I rate very highly. He goes beyond the more narrow concept of planning and offers the first German account of the defense of Berlin to be based upon thorough research. I attach great importance to this study from the standpoint of military history and concur with the military opinions expressed by the author.

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Colonel Guenther Hartung, Uetzersteig 12 - 14, Berlin-Gatow, Colonel Hartung was the leader of a circle of contributors consisting of eight former fellow-combatants livingin Berlin. Their contributions have been compiled by him and are included under his name in the supporting studies.

Lieutenant Colonel Ulrich de Maizieres, Argelander Strasse 105, Bonn, formerly in the Operations Branch of the Army General Staff.

Colonel Gerhard Roos, Jenaer Strasse 9, Berlin-Wilmersdorf, formerly Chief of Staff of the Inspectorate of Fortifications.

Colonel Hans-Oscar Woehlermann, Geldernstrasse 48, Koeln-Nippes, formerly Artillery Commander of the LVI Panzer Corps.

In addition to the above-listed home workers, the following persons were included:

From the Army High Command Generalmajor Erich Dethlefsen, General-major Illo von Trotha, Colonel Bogislaw von Bonin, Colonel Karl W. Thilo.

From Army Group Vistula: Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici, Colonel Eismann.

From the Replacement Army: Generalmajor Laegeler.

From Deputy Headquarters, III Corps: Generalleutnant Helmut Friebe, Lieutenant Colonel Mitzkus.

Commander of the Berlin Defense Area, Generalleutnant Helmuth Reymann; his Artillery Commander, Lieutenant Colonel Edgar Platho.

From the Wehrmacht Area Headquarters: Major Pritsch, Lieutenant Colonel Karl Stamm.

From the Luftwaffe: Colonel Gerhardt Trost.

From Ordnance: Chief Ordnance Technician (Master Sergeant) Schmidt.

From the Party: Dr. Hans Fritsche.

Also consulted were the Police Commander for Berlin, Colonel Krich Duensing, and numerous veterans of the fighting, from platoon leaders to regimental commanders, including leaders of such organizations as the Volkssturm and the Plant Protection Service.

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

The research In connection with the present topic proved to be unusually difficult. It became evident almost from the start that no Iong-range, strategic planning for Berlin's defense had ever been conducted. Instead, all plans had been dictated directly by the current situation.

This planning entailed collaboration from the most varied authorities: (1) Hitler, (2) The Army High Command, (3) The Replacement Army, (4) Army Group Vistula, and (5) The Nazi Party, National Defense Commissioner.

Agencies, responsible for carrying out the defense plans were (1) Deputy Headquarters, III Corps, [*] (2) The Commander of the Berlin Defense Area, (3) Troop units from all branches of the Wehrmacht, the SS, and the Police, and (4) the Party Organizations.

[* - Each Wehrkreis, or basic military area, was under the command of a corps headquarters. In wartime this headquarters went into the field aid was replaced in the Wehrkreis by a deputy corps headquarters. (Editor)]

Accordingly, the author had to find persons from all of the above organizations who were able to give information. No documents or other written data were discovered, nor was any information found in the later literature of the war which could be considered valid source material.

The only course left to the author was to solicit information from a large number of persons who participated in the operation. Nearly all the answers were made from memory, as only a few of the persons questioned are in possession of notes which they made at the time. Consequently the data thus obtained had to be compared and, where necessary( supplemented and corrected by enlisting the aid of still other collaborators.

Generalleutnant a.D. Reymann, who from 8 March 1945 to 22 April 1945 was Conmander of the Berlin Defense Area, for reasons of principle preferred not to collaborate.[*] The work, therefore, had to be accomplished without his assistance. Later, at the personal request of the author, General Reymann checked the manuscript for factual accuracy. The drafts were also examined by Generaloberst a.D. Heinrici, former commander of Army Group Vistula. It is assumed, therefore, that an acceptable degree of accuracy was attained. In matters of detail the possibility of error still exists. A few contradictions which could not be fully clarified are indicated in footnotes.

[* - A number of former German officers have refused to collaborate with the Historical Division while their comrades are still imprisoned for war crimes.]

To aid evaluation, this text is accompanied by

a. A chronological outline of the course of events.

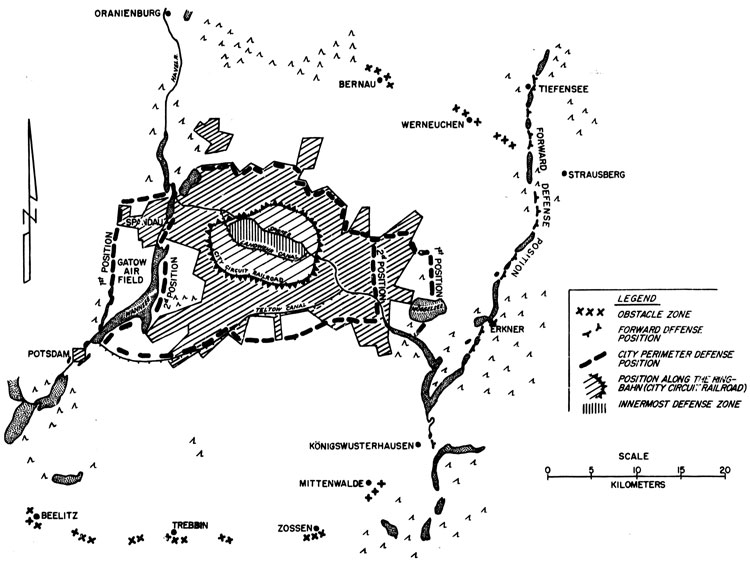

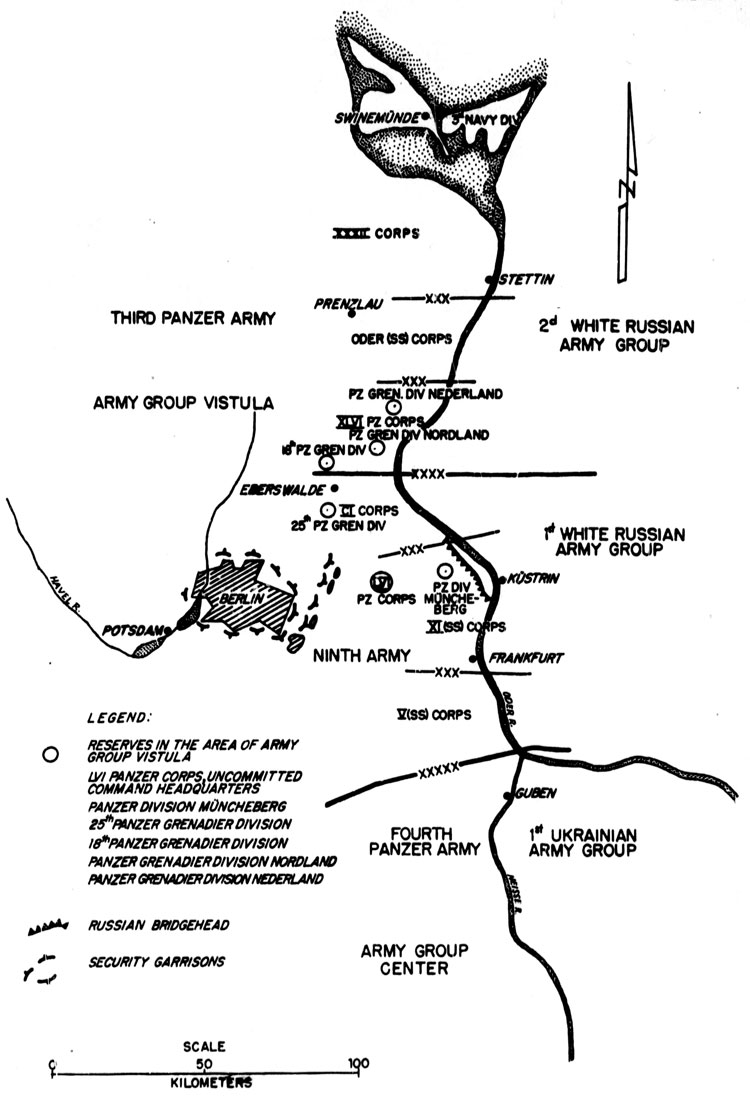

b. Sketch 1, showing the distribution of German forces on 14 April 1945 before the beginning of the large-scale Russian offensive on the Oder.

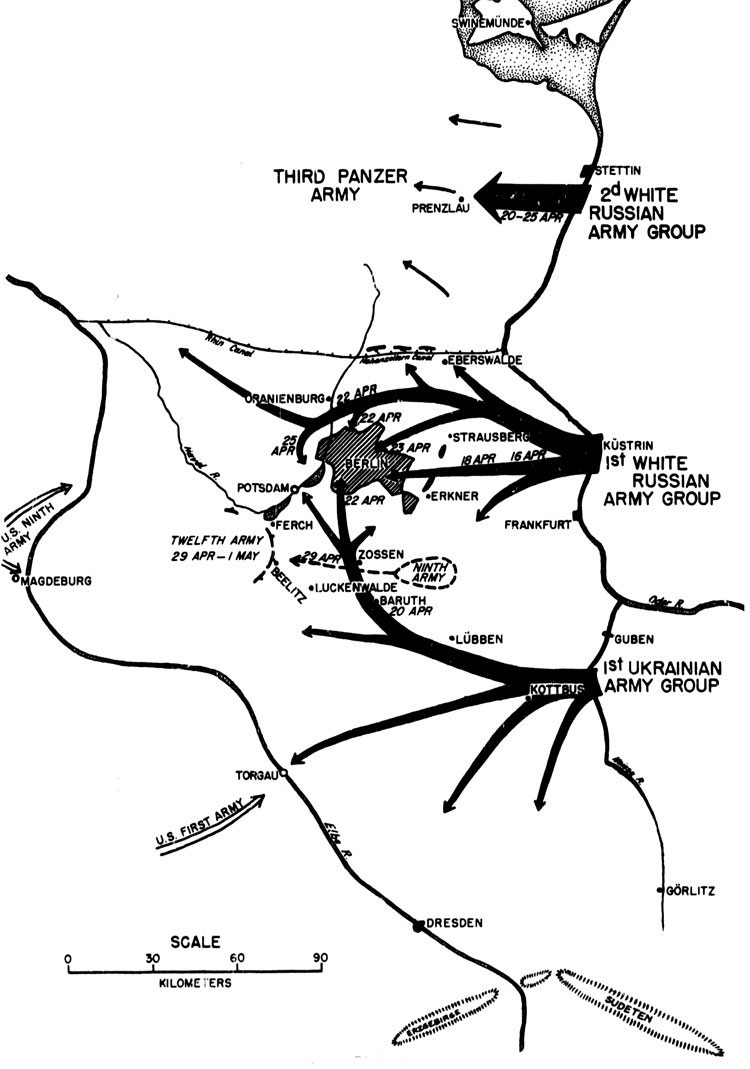

c. Sketch 2, showing the main lines of attack of the Russian offensive.

In preparing this study, the author acquired an over-all view of the actual course of combat operations. Since it seemed desirable not to overlook the knowledge thus gained a short account of the action is included as an appendix.

SKETCH 1. THE DISTRIBUTION OF GERMAN FORCES ON 14 APRIL 1945 BEFORE THE BEGINNING OF THE RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE ON THE ODER

SKETCH 2. THE MAIN LINES OF ATTACK OF THE RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE

Chronological Outline of the Course of Events in the battle for Berlin

31 January 1945

Weak motorized Russian forces penetrate across the ice of the Oder into the vicinity of Stausberg. Berlin is alerted.

February - March

The Oder defenses are built up.

Early February

General der Infanterie von Kortsfleisch, commanding general of Deputy Headquarters, III Corps, and at the same time Commander of the Berlin Defense area, in relieved by Generalleutnant Ritter von Hauenschild.

22 March 1945

Generaloberst Heinrici assumes command of Army Group Vistula.

29 March 1945

Generaloberst Guderian, Chief of the Army General Staff, is relieved by General der Infanterie Krebs.

12-15 April 1945

The Russians make preliminary attacks to widen the Kuestrin bridgehead.

16 April 1945

The Russians begin a large-scale offensive from the Kuestrin bridgehead and across the Neisse.

18 April 1945

Counterattack by the 18th Panzer Grenadier Division is unsuccessful. Oder and Neisse fronts collapse.

19 April 1945

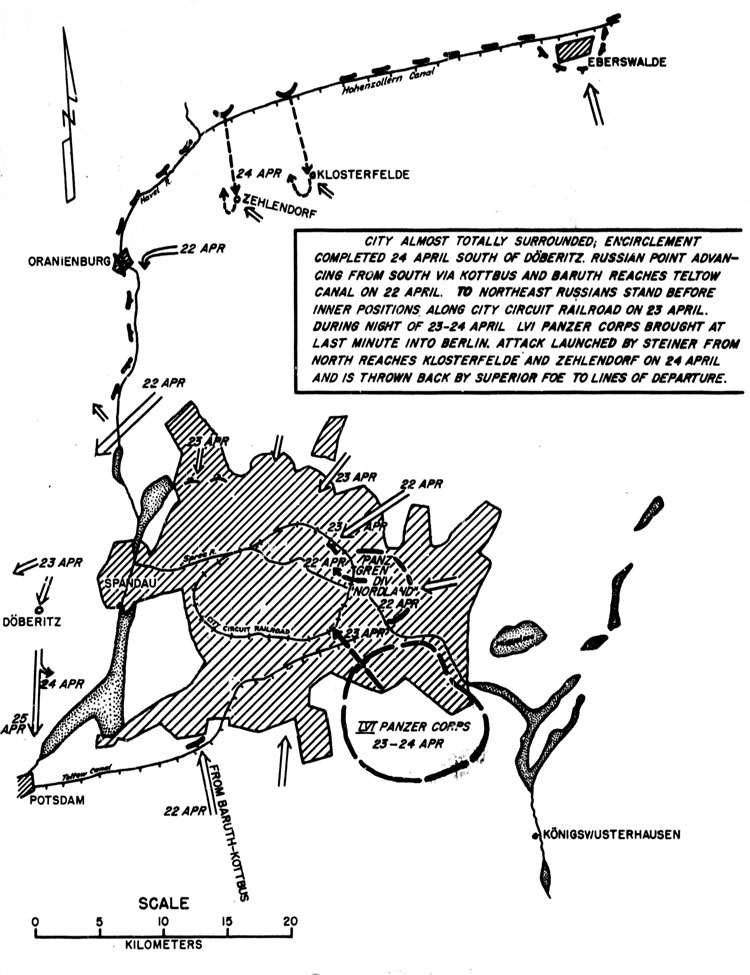

Berlin Is placed under the command of Army Group Vistula. The army group assigns SS Obergruppenfuehrer Steiner the task of safeguarding the Hohenzollern Canal and vainly requests the withdrawal of the center and right wing of the Ninth Army from the Oder. The Russians push forward from the south to the rear of the Ninth Army in the direction of Berlin.

20 April 1945

The Russians reach Baruth from the south. To the east of Berlin an unsuccessful counterattack is made by the 18th Panzer Grenadier Division and Panzer Grenadier Divisions "Nordland" and "Nederland." Army Group Vistula orders all available forces to be moved out of Berlin to the defense positions. Hitler decides to remain in Berlin. The Russians launch a large-scale offensive south of Stettin.

21 April 1945

The Soviets reach Zossen, Erkner, and Hopegarten.

22 April 1945

The Russians reach the Teltow Canal near Klein-Machnow from the south and the outskirts of the city at Weissensee and Pankow from the east. They cross the Havel River north of Spandau. Generalleutnant Reymann is replaced by Colonel Kaether. Army Group Vistula is excluded from command in Berlin; the city is placed under Hitler's personal command. Hitler moves Panzer Grenadier Division "Nordland" to Berlin. Army Group Vistula instructs Steiner to launch a relief attack. The LVI Panzer Corps receives orders to proceed to Berlin, but withdraws to the south.

23 April 1945

The Russians attack along the Teltow Canal, against Friedrichshein, and near Tegel. Generalleutnant Weidling becomes Commander of the Defense Area and moves the LVI Panzer Corps to Berlin. The Army High Command and the Wehrmacht High Command leave Berlin. Hitler orders an attack by the Twelfth Amy from the southeast, aiming at Berlin.

24 April 1945

The Russians cross the Teltow Canal; strong fighting progresses in the eastern part of the city. The Russians advance west from Spandau and close off Berlin from the west. Steiner's troops are thrown back to their line of departure after attacking with initial successes.

25 April 1945

The Russians break through south of Stettin.

24 April - 1 May 1945

Berlin's defenders stage severe retarding actions.

29 April 1945

The Twelfth Army reaches Beelitz - Perch. Generaloberst Heinrici is relieved of the command of Army Group Vistula.

30 April 1945

Hitler commits suicide. Remaining elements of the Ninth Army break through to the Twelfth Army.

1 May 1945

Negotiations for surrender are begun. Elements of the Berlin garrison attempt to escape.

2 May 1945

Berlin surrenders.

CHAPTER 2 THE VARIOUS VIEWPOINTS

I. GENERAL

The decision to defend Berlin to the last man was of crucial importance both to the troops involved and, even more, to the city's several million inhabitants. Special attention must be given to the command authorities who made this decision and carried it through and those who attempted to counteract it. Only thus can one see an over-all picture of the plans prepared for the defense of the city.

II. HITLER

To Hitler the defense of every city was important, so that to him it was a foregone conclusion that the capital of the Reich would be defended. Human considerations did not concern him. On the contrary, he stated on numerous occasions that the German people, if defeated, would be unworthy to survive the struggle.

The thought of his own downfall cannot have been absent from Hitler's mind during the last months. On the other hand, almost to the very end he seems to have clung — sporadically, at least — to the hope that a shift in front by the Western Allies might change the tide of war. This hope is indicated by repeated statements of the Fuehrer.

Hitler was an advocate of stubborn defense, particularly of cities. The successful defense of Leningrad and Stalingrad by the Russians and of Breslau by the Germans seemed to him to support his views. However, it was no longer possible at this stage of the war for a strategic concept to serve as a basis for the defense of Berlin.

At the beginning of February Hitler declared Berlin a fortified place.[*] By virtue of this proclamation and the fact that all vital decisions regarding defense measures were made by him personally, he assumed full responsibility in the battle for the capital.

[*- The exact date could not be determined from documentary sources. (Author)]

Until the Russians reached the Oder at the end of January 1945, no provisions were made for the defense of Berlin, Certain security measures taken before this time by the Wehrmacht Area Headquarters served only to combat internal disturbances which could be expected from the masses of foreign laborers employed in and around the city.

Hitler now ordered the building up, supplying, and tactical distribution of a security garrison, but failed to set up a general plan of defense stipulating with what forces Berlin was to be defended. The security forces available in the city were far too weak for a protracted defense. Moreover, the best of these troops from the standpoint of combat effectiveness had been moved out of the city to the Oder. Thus the question of forces to be used in the defense depended upon improvisation.

Hitler informed the Commander of the Berlin Defense Area, Generalleutnant Reymann, that in the event of a battle for the capital sufficient front-line troops would be made available. A plan based on such an "assurance" naturally contained a great element of uncertainty, because it was impossible to know whether troops could be brought in from the eastern front in time and in what condition they would be. No assurance was ever given by Army Group Vistula that such troops could be provided.

At first the defense of Berlin lay along the Oder, and an attempt was made to reinforce that front as much as possible. Upon inquiring at the beginning of April what plan was envisaged in case the Oder front collapsed, Army Group Vistula was told that the Third Panzer Army was to hold fast along the lower Oder, while the army group was to fall back with the Ninth Army to a line along the canals between Eberswalde and the mouth of the Havel in order to form a northern Kessel [*] between the lower Elbe and the Oder. It is not necessary here to discuss the prospects of defending such an extended Kessel. It is important to note, however, that the army group was not ordered to include Berlin in its own defense plan or to divert troops to the city, A large southern Kessel was to be formed concurrently with that in the north. For himself, Hitler foresaw the possibility of retreating to the Bavarian mountain fortress.

[* - As used here, Kessel (literally kettle) means an island of defense or an all-round or enclosed defensive area (Editor)]

Nevertheless, it must not be presumed that, if this plan had been carried out, Berlin would have been abandoned without a struggle. Rather the defense would have been carried out along the pattern established in many other cities by forces ordered up in accordance with the particular circumstances. Meanwhile, in the absence of Hitler, Army Group Vistula and the Commander of the Defense Area would have had sweater freedom of operation.

As the collapse of the Oder front became imminent, Hitler tried desperately to close the gaps in the line by giving orders to attack. Even he was forced to admit that the defenders were not succeeding in throwing back the attacking Russian spearheads; nevertheless, it would still have been possible around 19 April to withdraw considerable forces from the Ninth Army into Berlin by abandoning the parts of the Oder front still being held. Hitler, however, bluntly refused Army Group Vistula's urgent daily requests {which were prompted by other considerations) that the Ninth Army be withdrawn from the Oder. Not until 23 and 24, April did he order any troops into Berlin and then only those of the LVI Panzer Corps, which were fighting before the gates of the city. By this time the Russians had already penetrated the city at several points, so that the position along the city perimeter could no longer be occupied according to plan.

As early as 20 - 22 April Hitler apparently felt that the end was near; in any case, on 20 April he announced his decision to remain in the city. Then, under the influence of his entourage, he gathered courage once more and tried to continue the struggle by defending the capital and at the same time by ordering relief attacks from the west and the north. Here again the hope for a shift in front by the Western Allies may have been a motivating factor. Beginning about 23 April the city put up particularly stiff resistance.

Only after the relief attacks had proven hopeless and a meeting of American and Russian troops had been effected near Torgau without producing the hoped-for clash did Hitler concede defeat and commit suicide. Before his death Hitler issued written orders to the Commander of the Defense Area, leaving him free to attempt a break-out, but forbidding surrender. For a few hours Goebbels, as a minister of the Reich still present in Berlin, stepped into Hitler's place and forbade attempts either to break out or to surrender. He apparently tried at the last moment to come to an agreement with the Russians, offering to surrender on condition that they recognize a new government in which he would take part. When this failed, he also committed suicide.[*]

[* - Ploetz, Regenten und Reglerung der Welt. Teil II(A.G. Ploetz, Verlagsbuchhandlung fuer Aufbau und Wissen, Bielefeld, 1953). Published Allied accounts of the last days in the Reich Chancellory bunker state that Goebbels committed suicide before Hitler. (Editor)]

Apart from the fact that Hitler's behavior fails to reveal the slightest trace of any fueling of responsibility toward the German people as a physical entity, there are indications that at times his thinking was no longer rationale His estimate of the means at his disposal and the fighting power of the enemy were wholly unrealistic. On the other hand he was by no means insane in the medical sense. To the very end he managed to maintain his authority and power to command. The idea of a revolt in order to surrender the city without a struggle did not even occur to Hitler's immediate associates, since their own destiny was too closely linked to his. Outside this circle revolt was completely out of the question because of the extensive security measures that had been taken and because of the thin dispersal of authority.

III. THE ARMY HIGH COMMAND

The Army High Command had also failed to prepare an advance plan for the defense of Berlin. This may have been largely because those responsible wished to avoid a battle for Berlin. To Hitler's mind it would have been defeatism to take measures for defense west of the Oder as long as the German front was still on the Vistula. Moreover, after the dismissal of Generaloberst Guderian, the Army High Command had been transformed into an agency existing merely to carry out Hitler's orders. The Wehrmacht High Command had already been functioning on this level for a long time.

IV. ARMY GROUP VISTULA

The Commander of Army Group Vistula, Generaloberst Heinrici, had developed his own clearly thought-out plan. Assuming that the war would end soon after the anticipated collapse of the Oder front, he was concerned first, with saving as many German soldiers as possible from Russian captivity by shifting his troops to the area overrun by the Western Allies and, secondly, with protecting the population as much as possible from further loss of life and property.

According to this viewpoint a battle for Berlin should be avoided. To this end the army group did everything in its power.

At first Army Group Vistula agreed with Hitler that all available forces should be committed on the Oder front. In the plan for a northern and a southern Kessel the army group saw the possibility of moving the Ninth Army on either side of Berlin and past the city to the northwest. This was emphatically recommended to Ninth Army. In accordance with this recommendation the army's service trains not needed in the fighting were actually diverted toward the Mecklenburg area.

Undoubtedly the implementation of this plan would have been difficult for the combat elements of the Ninth Army, for the attack of the Russians was expected precisely along its left wing, which was the pivot point of any withdrawal to the northwest. The army group made allowance for this in advance by distributing its mobile reserves behind the left wing of Ninth Army, even going so far as to echelon them rearward a little toward the left. (See Sketch 1)

If the center and right wing of this army had been pulled back in time and full use had been made of the defense position for a delaying action, it would certainly have been possible to save the bulk of the Ninth Army and to preserve the coherence of the army group. At the Russian breakthrough to Berlin took shape, Army Group Vistula ordered the Commander of the Defense Area, Generaloberst Reymann, to move all available troops still fit for immediate action out of Berlin and into the defense position east of the city. These troops would then not be available for the actual battle for Berlin. A penetration of the defense positions would have resulted in the occupation of the city without a struggle, and the population would have been spared the horrors of a battle. The army group estimated that the first Russian armored units would reach the Reich Chancellery as early as 22 April. However, the measure ordered by the army group was only partially carried out. Only some thirty battalions were put on the march, General Reymann explaining that the limitation had been imposed by lack of transport facilities and the poor condition of the remaining battalions. Thus the bulk of the security forces stayed in Berlin.

The army group intention not to let any parts of the Ninth Army reach Berlin was not frustrated. Without consulting either the army group or Ninth Army or even informing them beforehand, Hitler withdrew the LVI Panzer Corps into Berlin. Requests by army group that the bulk of Ninth Army be saved from encirclement on the central Oder and withdrawn to the south of Berlin were refused. On the contrary, orders emanating directly from the Fuehrer instructed the Ninth Army in the sharpest terms to hold fast along the Oder.

For its part, on 22 April Ninth Army had ordered the LVI Panzer Corps to attempt a junction with the army southeast of Berlin. At the same time the commanding general of this corps, General der Artillerie Weidling, received Hitler's first order to move into Berlin. General Weidling decided not to go to Berlin, but to try to make contact with the Ninth Army to the south. Only after the order had been repeated on 23 April did he move the corps to Berlin.

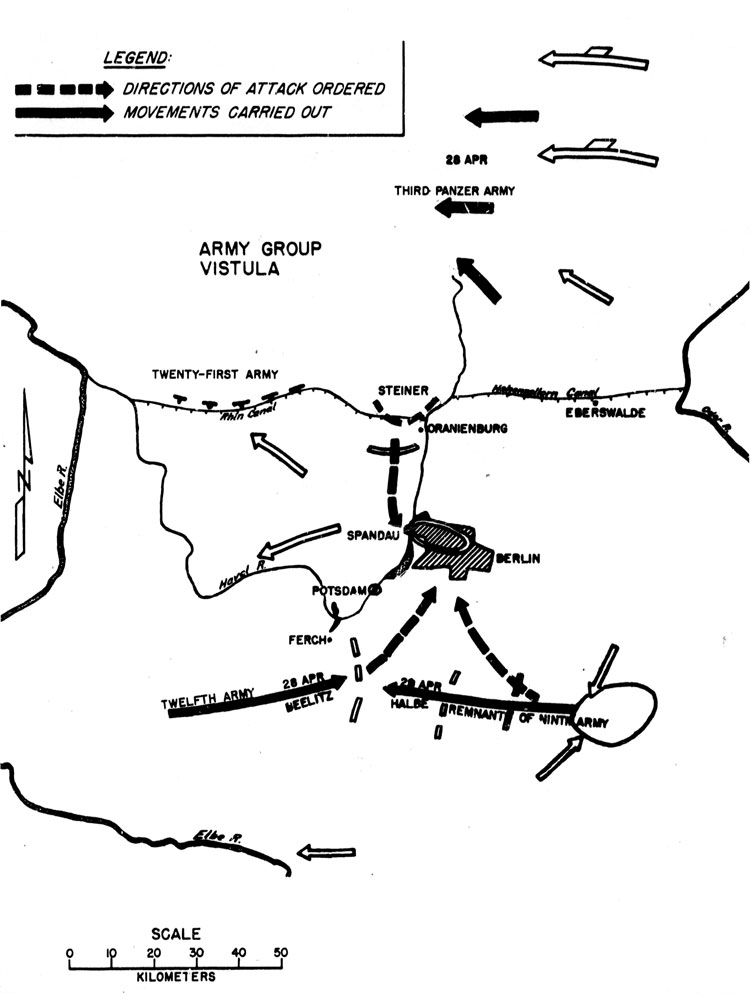

After the encirclement had been completed, Hitler ordered relief attacks aimed at Berlin. These were to be carried out by the Ninth Army from the south, the Twelfth Army from the west, and Army Group Vistula from the north. Army Group Vistula was to send all available forces to SS Obergruppenfuehrer Steiner in the area west of Oranienburg for an attack on Berlin-Spandau. Here too there arose a fundamental difference of opinion between Hitler and the army group.

Generaloberst Heinrici maintained that the ordered attack had absolutely no prospect of success. Consequently, in estimating the situation, he felt that bringing together all available forces near Oranienburg, as instructed, would necessarily lead to the destruction of the Third Panzer Army and Group Steiner as well, since the lines of the Third Panzer Army already had been pierced south of Stettin by strong Russian armored forces. In his opinion the formation of a group near Oranienburg was tactically desirable; not, however, to attack Berlin, but to protect the deep flank of the Third Panzer Army. All remaining available troops, however, had to be either sent to the Third Panzer Army, in order to make possible its withdrawal to the west (about 250 kilometers on foot), or used to extend the flank protection from Oranienburg to the junction of the Havel and Elbe Rivers, since a Russian thrust to the rear of the army group in the direction of Hamburg was taking shape in that sector.

The divergence in points of view led to a sharp clash between the army group and General Keitel, who urged holding the eastern front of tha army group and attacking near Oranienburg. General Keitel relieved General Heinrici of his command on 29 April. The withdrawals to the west were already well under way, however, so that it was still possible under General Heinrici's successor to "save" the bulk of the forces by letting then be captured by the Western Allies.

V. SUMMARY

This examination of the various viewpoints shows that Hitler and the Army High Command did not have a unified, constructive plan for the defense of Berlin, but that, apart from preparations for consolidating the limited resources at hand, the conduct of the defense was dependent at any given time on the situation as dictated by the Russians. General Heinrici's viewpoint could not prevail, since he did not have command authority at the decisive time and place. More will be said of this in the next chapter.

CHAPTER 3. ORGANIZATIONAL PLANNING

I. GENERAL

It is a matter of general knowledge that the German conduct of the war was characterized by top level disorganization, which increased as the war progressed.

The various theaters of war were divided between the Wehrmacht High Command and the Army High Command. Even after the eastern and western front had begun to draw closer together, a coordinated plan for the conduct of the war was not forthcoming. The Chief of the Army General Staff through the Operations Branch was responsible for operations only on the eastern front, whereas the other branches also under the Army General Staff — such as the Organization, Transportation, Signal, and Supply and Administration Brunches — were responsible for their respective services on all fronts.

Hitler seriously interfered with Army command channels by issuing direct orders. On the other hand, there was no clear and definite procedure for co-operation between the various branches of the Vlehrmacht. The Lufiwaffe, Navy, and Waffen-SS each operated on a highly independent basis to the detriment of the armed forces as a whole. The Todt Organization, and to a lesser degree the Reich Labor Service, followed military directives only within limits. The lack of co-ordination and the antagonism between the Wehrmacht and the Party led to strong tensions.

The cause of this confusion in the distribution of authority, which was an expression of profound spiritual disorganization, lay above all in Hitler's deep-rooted mistrust of his generals and the General Staff. By dividing authority, he tried to keep all the reins of Command in his own hand.

These circumstances were bound to have a fatal effect on the defense plans and on the battle for the capital, the seat of all top-level agencies of the Reich. It is a basic military principle that under such conditions all command authority should be concentrated in the hands of the commander responsible for the defense. In Berlin, however, this principle was disregarded to even greater extent than in Breslau or Koenigsberg.

II. MILITARY AGENCIES TAKING PART IN THE DEFENSE

Until 1 February 1945 the military needs of Berlin were the responsibility of the Wehrmacht Area Headquarters. This headquarters was subordinate to Deputy Headquarters, III Corps, and the latter, in turn, to the Replacement Army. The Replacement Army was directly subordinate not to the Army High Command but to the Wehrmacht High Command. The commander of the Replacement Army was the Reichsfuehrer of the SS, Heinrlch Himmler.

When at the beginning of February — probably on 1 February 1945 — Berlin was declared a fortified place, Deputy Headquarters, III Corps, while still retaining the functions previously assigned to it, was designated the office of "Commander of the Berlin Defense Area." Initially, the commander was General der Infanterie von Kortzfleisch; as of the beginning of February, he was replaced by Generalleutnant Ritter von Hauenschild.

Under the latter's successors, Generalleutnant Reymann, the office of "Commander of the Berlin Defense Area" was separated from Deputy Headquarters of III Corps.

On 19 April the Commander of the Berlin Defense Area was subordinated to Army Group Vistula.[*]

[* - General Reymanns, Colonel Eismann, and Generaloberst Heinrici give conflicting information regarding the date of this change. The date indicated here, given by Heinrici, is the most probable since it is based on diary entries. (Author)]

On 22 April this order was revoked, and Berlin was placed directly under the Army High Command. On the same day General Reymann was relieved of his post as Commander of the Defense Area and assigned as commander of Armeegruppe [*] Spree. Colonel Kaether succeeded him as Commander of the Defense Area.

[* - A weak improvised army under an army commander with an improvised army staff. (Editor)]

On 23 April the commanding general of the LVI Panzer Corps, General der Artillerie Weidlings became Commander of the Berlin Defense Area, while still retaining command of his corps.

On 23 - 24 April the Army High Command and Wehrmacht High Command left Berlin; on 25 April these agencies were merged.

III. AUTHORITY OF THE INDIVIDUAL MILITARY AGENCIES

1. Wehrmacht Area Headquarters.

The Wehrmacht Area Headquarters was under Deputy Headquarters, III Corps, and consequently under the Replacement Army. Its tasks included the usual administrative and housekeeping duties of a garrison headquarters, as well as the guarding of bridges, supply depots, and foreign workers, a great number of whom were in Berlin. It also collaborated in removing debris caused by bombing and especially in clearing thoroughfares.

For this purpose the Wehrmacht Area Headquarters had at its disposal military police, guard battalions (local security units), a few construction battalions, and the Berlin Guard Regiment. When Berlin was declared a fortified place, however, it was not the Wehrmacht Area Headquarters that was charged with the defense, but Deputy Headquarters, III Corps, which was designated as the office of the "Commander of the Greater Berlin Defense Area."

The Wehrmacht Area Headquarters retained its earlier functions, with emphasis placed on rounding up the numerous stragglers. Its participation in the defense was consequently of a secondary nature, especially since, with the beginning of the battle, the task of rounding up stragglers was largely taken over by the Party Security Service.

2. Deputy Headquarters. III Corps (Simultaneously Office of the Commander of the Berlin Defense Area). In addition to its function as Deputy Headquarters, this agency was responsible for the defense of the Wehrkreis and of the Berlin Defense Area.

Accordingly, after the collapse of the Vistula front, the commanding general - initially General der Infanterie von Kortzfleisch — organized a rear defense position east of the Oder and, when this was immediately pierced, another position on the Oder itself. In the midst of the undertaking, at the beginning of February 1945, General von Kortsfleisch was removed from his post. The reason for this action is to be sought in the poor relations which had developed between him and the Gauleiter[*] for Berlin, Goebbels, whose encroachments on the authority of the Army General von Kortzfleisch had sharply opposed.

[* - Official in charge of a Nazi Party administrative area (Gau), (Editor)]

Generalleutnant Ritter von Hauenschild was appointed his successor, and was relieved of responsibility for the Oder front by Army Group Vistula. Under his command the preparations for the defense of Berlin were begun.

To have one person performing a dual mission proved to be a disadvantage, however. As commanding general of the Deputy Headquarters and commander of Wehrkreis III, General von Hauenschild's primary task was to send as many troops as possible to the Oder front. As Commander of the Berlin Defense Area, it was in his interest to retain as many troops as possible in Berlin. As a result, the defense of Berlin received secondary consideration.

When General von Hauenschild became sick at the beginning of March 1945, Generalleutnant Reymann was appointed his successor. The new commander separated the Defense Area and the Deputy Headquarters. He himself became Commander of the Defense Area, while General der Pioniers Kuntse was named Deputy Headquarters Commander. The Deputy Headquarters was thereby excluded from command in the defense of Berlin. The headquarter staff left the city shortly before the encirclement.

3. Commander of the Defense Area (After Separation from Deputy Headquarters, III Corps). Generallertnant Reymann was assigned his own staff. His Chief of Staff was Colonel (GSC) Refior. Under General-leutnant Reymann all preparations for the defense were energetically continued, even though, because of limited means, only makeshift measures could be taken.

The Defense Area was divided into eight sectors, designated by the letter A through H. These sectors radiated outward from the position along the town circuit railroad. In each sector a field grade or general officer was assigned as sector commander with the authority of a division commander. For this it was necessary to fall back on officers from antiaircraft artillery and home Army units who lacked practical combat experience.

Even in filling subject or command positions, persons with front-line experience were rarely available.

On 23 April 1945, just as the Russians were at the very gates of the city, Generalleutnant Reymann was relieved of his post and appointed commander of Armeegruppe Spree, which for practical purposes consisted of one understrength division. His removal from Berlin was obviously ordered at the insistence of Goebbels whose initially favorable attitude toward General Reymann had radically altered. When Generaloberst Helnrici to whom Berlin was at this time subordinated, learned of the change, he ordered General Reymann to remain at his post because it seemed to him foolhardy to change commanders at a time when the danger was most acute. He was not able to make his orders prevail, however, and General Reymann was forced to take over command of Armeegruppe Spree. With part of this force he was driven back to Potsdam and surrounded.

Meanwhile, on 22 April, a new commander was sought. General Kuntze was named first, but for reasons of health he declined. Next a major was considered for the appointment, but was rejected as too young. Finally, Colonel Kaether, until then leader of the National -Socialist guidance officers, became Commander of the Defense Area. For this purpose he has promoted first to Generalmajor and immediately afterward to Generalleutnant. In both cases, however, only for the duration of his appointment. This was a unique occurrence in the German Army; but the promotions were of little use to Kaether, as he was in command for barely two days.

On the evening of 23 April Hitler ordered the commanding general of the LVI Panzer Corps, General der Artillerie Weidling, under threat of death, to report at the Fuehrer Bunker. It was generally supposed that General Weidling would be shot because his corps had been thrown back by the Russians. Weidling, however, made such a favorable impression that Hitler immediately appointed him Commander of the Defense Area while retaining him as commander of the panzer corps. Thus he became the fifth commander of the Defense Area in less than three months and the third within two days.

General Weidling utilized parts of the Reymann staff, so that in addition to his chief of staff, Colonel (G3C) von Duffing, Colonel (GSC) Refior Has retained as deputy chief of staff. His artillery commander, Colonel Woehlermann, assumed command of all artillery in Berlin; Lieutenant Colonel Platho, who until then had been artillery commander of the Defense Area, was subordinated to him.

General Weidling placed two sectors of the Defense Area under each of his four division commanders in order to integrate the permanent local organization with leadership possessing front-line experience. In carrying out this plan, he immediately encountered opposition. One valiant but self allied sector commander, Lieutenant Colonel Baerenfaenger, who had just been promoted to Generalmajor, refused to become subordinate to the front-line division commander responsible for his sector. Such difficulties coupled with the necessity for immediately employing the incoming troop units of the panzer corps at the focal points of the battle resulted in constant changes and delays, so that it can hardly be said that the planned organization actually became operative.

The command post of the Defense Area was at first located in a building of the corps headquarters on Hohenzollerndamm. As the Russians approached this vicinity on 25 April it was moved to the Bendler Bunker, General Weidling himself found it necessary to remain most of the time at the Reich Chancellery.

4. Army Group Vistula. Berlin lay only seventy kilometers to the rear of the main line of resistance of the army group, whose position extended from the junction of the Neisse and Oder Rivers to the Baltic and whose front lines roughly followed the course of the Oder.

In case of a Russian break-through, Berlin was to have been incorporated immediately into the army group's zone of operations. The protection of the Reich capital necessarily lay in the letter's hands. It would therefore have been logical to place the Defense Area under th« army group from the start. While this was not done, the army group had expected that such a subordination of command would be effected at the critical moment and had asked to be informed by General Reymann or his chief of staff of the progress of all defensive measures. The army group also tried to prevent the demolitions from being carried out, in order to save the civilian population from their far-reaching consequences. General Heinrici reserved to himself the decision to order the demolitions in case the Defense Area should be subordinated to his command.

On 19 April, after the collapse of the Oder front east of Berlin, the Defense Area was placed under the command of the army group. Thereupon the latter proceeded to carry ovtt its plan for moving all battle-worthy security troops out of Berlin and into the defense position. This intention was only partially realized.

Since the army group could scarcely handle the mass of requests and decisions relative to Berlin from its headquarters near Frenslau, it in turn placed the Defense Area under Ninth Army; which was fighting east of the city. However, the army commander, General der Infanterie Busse, refused to accept this responsibility on the valid grounds that in the thick of battle he could not concern himself with the Defense Area, especially since the Ninth Army's center and right wing were still fighting on the Oder. The army group thereupon rescinded the order and retained direct command of Berlin.

The difficult question of the chain of command might conceivably have been solved by introducing a new army command (possibly under SS Obergruppenfuehrer Steiner) between the Ninth Army and the Third Panzer Army with headquarters in Berlin. Under this command could have been placed the Defense Area and all forces south of Berlin Armeegruppe Spree), east of Berlin (the forces guarding the forward defense position and the LVI Panzer Corps), and northeast of Berlin (security detachments in the Eberswalde - Oranienburg area). This solution would not only have required preparation, however, but it ran counter to the plan of the army group to evacuate the city without fighting.

The subordination of the Defense Area to Army Group Vistula ended when Hitler assumed direct command of Berlin on 22 April.

Even during the time that the army group commanded the Defense Area, Hitler interfered with the chain of command. This is especially evident in the dismissal of General Reymann without consultation with the army group and over its protests. Armeegruppe Spree, which was to counter the Russian thrust from the south by way of Luebbenau, was subordinated neither to Army Group Vistula, Ninth Army, nor the Defense Area, but was placed directly under the Army High Command. A particularly flagrant interference with the command authority of the army group occurred on 23 April when Hitler moved the LVI Panzer Corps, which was subordinate to Ninth Army, into Berlin without informing either the army or the army group. This action had the following consequences:

a. Berlin obtained troops which for a while were able to carry on the battle for the city.

b. The Ninth Army was now outflanked from the north as well as from the south and thereby encircled.

c. Army Group Vistula disintegrated and the Russians were able to push westward, north of Berlin, Within the LVI Panzer Corps difficulties of command also arose, SS Panzer Grenadier Division "Nordland" tried to break away from the LVI Panzer Corps, to which it was subordinate, and effect a junction with the security troops of SS Obergruppenfuehrer Steiner, This intention was not carried out, since on direct orders from Hitler, and again without corps' knowledge, the division was brought straight to Berlin. This incident led to the temporary dismissal of the division commander.

5. The Army High Command. A clear decision to determine who would command the Defense Area had not been made by the Army High Command. From the beginning Berlin should have been placed either under Army Group Vistula or the Army High Command. Instead, orders came exclusively in the form of instructions from the Fuehrer. The commander of the Defense Area was left "hanging in the air," since he could not consult Hitler on every detail.

The subordination of the Defense Area to Army Group Vistula would have clarified the situation if Hitler and the Army High Command had not constantly issued orders outside of command channels. Once the army group was excluded from command, however, complete subordination of the Defense Area to Hitler became clearly established. Hitler was now nominal as well as actual combat commander of Berlin.

With the exception of certain individuals, the Army High Command and the Wehrmacht High Command left Berlin on 23 - 24 April. On 25 April the two agencies were merged. On Hitler's behalf, Field Marshal Keitel and Generaloberst Jodl now urged the Twelfth Army and Army Group Vistula to launch relief attacks. The contradictory views which now came to light led on 29 April to General Heinrici's removal, a move, however, which could no longer affect the fate of Berlin.

IV. CIVIL AGENCIES

1. Reich Defense Commissioner. Along with the military agencies, the Gauleiters, as Reich Defense Commissioners were responsible for the defense of the Reich territory.

They were responsible for all measures regarding the civilian population, the organization and training of the Volkssturm, and the construction of field fortifications.

There was no clearly-defined division of authority between the military agencies and the Reich Defense Commissioners, although they were expected to work together. The territorial authority of the Army ended ten kilometers behind the battle line. To the rear of this line, all measures not of a purely military nature — even the construction of field fortifications by civilian labor — were subject to the approval of the Reich Defense Commissioner. He was also responsible for carrying out these measures with the aid of the civilian population and the Volkssturm.

This dualism had serious consequences. In many instances, especially in the construction of field fortifications, the Army attempted to take matters into its own hands, while the Reich Defense Commissioners jealously guarded their own prerogatives.

The atmosphere between the two authorities tended to be highly strained.

As a result, numerous rear positions were laid out without the slightest understanding of tactical requirements. A great number of antitank obstacles were constructed, which were either totally ineffective or so hindered friendly troop movements that they had to be destroyed. Construction workers and materials were taken away from the forces in the field. Weapons and ammunition urgently needed to an strong young replacement troops were hoarded for use by old Volkssturm men far to the rear.

The Volkssturm, the tactical use of which was to have been left to the discretion of military authorities, received orders from the Party even during battle. One report describes how during the fighting a Volkssturm battalion in Berlin received orders alternately from both the sector commander and the Party district headquarters. Since these orders were usually contradictory, the battalion commander was genuinely happy when the Party district headquarters waa destroyed by bombs.

The Reich Commissioner for Berlin, Goebbels, and the Commissioner for Brandenburg, Stuerz, often worked at cross purposes. In one instance, without telling anyone, Stuerz withdrew a Brandenburg Volkssturm battalion that was assigned in Berlin, leaving a gap In the city's defense lines on the following day.

Goebbels clearly regarded the Commander of the Defense Area as his subordinate. Talks between the two took place in Goebbels' office. Every Monday a so-called "major meeting of the War Council" took place under Goebbels. leadership to discuss the defense. Those taking part included the combat commanders, representatives of the Luftwaffe and the Labor Service, the Mayor of Berlin, the Chief of Police, the Commander of the Wehrmacht Area Headquarters; the Administrative District Chief, higher ranking SS and police leaders, SA Standartenfuehrer Bock, and representatives of the Berlin industries, Goebbels also issued "orders for the defense" which prescribed certain military measures. His influence on the dismissal of commanders has already been shown. In describing the harmful Influence of the Reich Defense Commissioner, it must not be overlooked that the rigorous utilization of the civilian population provided the troops in the field with additional forces, particularly construction manpower. National-Socialist terror tactics, combined with clever propaganda, made unlikely any attempts on the part of some of the population to sabotage the combat efforts of the field troops.

2. The Hitler Youth. The Hitler Youth were led by Reich Youth Leader Axmann, who called them up for battle and committed them to action, partly on his own initiative and partly in agreement with the Commander of the Defense Area. On 24. April a Hitler Youth brigade armed with Panzerfaeustas[*] appeared in the Strausberg region to hunt down Russian tanks on a freelance basis. In response to urgent protests from General Weidling, Axmann tried to withdraw this youthful and inexperienced brigade from the fighting, but he was no longer able to get his orders through.

[*- Panzerfaust is a recoilless antitank grenade and launcher, both expendable(Editor)]

In Berlin itself the Hitler Youth fought partly in separate battalions and partly as small units attached to the field forces or the Volkssturm.

The use of the Hitler Youth as a combat force had not been anticipated, and their commitment was not included in the plans of the Defense Area. When eventually called upon, the Reich Youth Leader and subordinate Hitler Youth leaders loyally followed instructions of the military agencies.

3. Other Agencies. The Reichsfuehrer of the Waffen-SS and Reichamsrschall Goering refrained from exerting direct influence on the issuing of orders. Both, however, held back appreciably strong forces in the vicinity of Berlin as a personal bodyguard, end released these troops only hesitatingly and tardily. Consequently, they could not be included in the defense plans. All attempts by Army Group Vistula to secure blanket authority over these troops were unsuccessful.

The 1st Flak Division, which was assigned to Berlin, did not become subordinate to the Defense Area until initial contact had been made with the enemy. The difficulties of planning inherent in this arrangement were reduced by collaboration with the division commander, Generalmajor Sydrow.

On the other hand, little co-operation was received from SS Brigade-fuehrer Mohnke, commander of the SS troops responsible for the security of the government quarter. Only with the beginning of the fighting were these troops subordinated to the Defense Area. The Todt Organization, and to a lesser extent the Reich Labor Service, in many instances evaded orders of the Commander of the Defense Area by invoking their own authority.

V. THE COMMAND SYSTEM

The giving of commands and the transmission of messages suffered from the fact that the command system was no longer equal in all sectors to the demands of a major battle. Not only minor units, but whole divisions, as well as the headquarters of CI Corps, the staff of Army Group Vistula, and the staffs of the Berlin defense sectors, were improvised in the greatest haste.

There were serious shortages of trained signal personnel, signal equipment, motor vehicles, and gasoline. The lack of telephone equipment could partly be compensated for, since fighting on home territory made possible full use of the peacetime telephone network. This advantage was outweighed, however, by the fact that newly-created task forces and staffs could not acquire any experience in working together. As a result, there was insufficient information at higher levels regarding the actual situation on vital sectors of the front, and communication through command channels was often slow.

Thus, from 18 April on, the Ninth Army and Army Group Vistula were inadequately informed as to the situation on the Ninth Army's northern wing. Army Group Vistula knew nothing about the appearance of Russian tanks south of Berlin near Baruth on 20 April.

The permanent local units along the Teltow Canal were completely surprised to find themselves face to face with Russian tanks on 22 April. The bringing up of Panzer reserves (Panzer Grenadier Divisions "Nordland" and "Nederland") to the breach in the Oder defense line took an unduly long time.

VI. SUMMARY

A well-conceived and energetic plan for instituting defense measures and conducting the battle could have been realized only if the responsible commander of the Defense Area had received uniform instructions and been given over-all authority at lower levels.

Instead, he was subject to orders and instructions from both military and civil authorities, whose varied interests were apt to be conflicting or inconsistent. This may be illustrated further by the following incident.

General Reymann intended to convert the main east-west thoroughfare of the city [*] into an airplane landing strip. For this purpose it was necessary to remove the bronze lamps along the street and the nearby trees in the Tiergarten, which had already been severely torn up by bombs.

[* - Charlottenburgerstrasse]

To do this General Reymann had to obtain Hitler's personal authorization. Hitler gave permission to remove the street lamps, hut not the trees. As the dismantling of the street lamps got under way, Reich Minister Speer, who was charged with plans for rebuilding Berlin, raised objections and obtained from Hitler an order forbidding their removal. General Reynann was forced to call on Hitler again in order to procure another authorization to proceed.

While relations between the commander and the agencies above him were badly strained, the distribution of authority at lower levels was even more chaotic. The commander in Berlin had unlimited authority only over the few Amy units present in the city. He had only very limited authority over the Volkssturm, (the bulk of the available defense forces), SS troops, Flak units, Hitler Youth, and the Todt Organization and Labor Service. He had no authority at all over the population, which carried the greatest burden in the construction of positions.

Another example will serve to illustrate this limitation of authority. The Commander of a battery manned by permanent local troops received a Volkssturm platoon to serve his guns. Yet, he was not allowed to give these men orders except during battle, and so was reduced to using persuasion. Under these circumstances even a man with the clear vision and conscious purpose of Generalleutnant Reymann could accomplish little.

The broad organizational picture gives indications of complete chaos. The overlapping, confusion, and contradiction in the issuing of orders, the precipitous changes in the distribution of authority, and the constant dismissal and elimination of responsible individuals are signs of fundamental disintegration and imminent collapse. The effects on the fighting troops were devastating. Even now all accounts by veterans of the fighting in Berlin speak of a complete breakdown in leadership, and many even of sabotage. This impression was certain to be widespread.

Just what happened to a commander who failed to defend a fortified place to the last man can be seen in the case of the Commander of Koenigsberg, General der Infanterie Lasch. General Lesch was sentenced in absentia to death by hanging; the sentence was made public in a communique of the High Command and his whole family was placed under arrest.

The object of this study is neither to accuse nor to justify. Nevertheless, the conclusion must be reached that it was not incompetence - spart from individual instances — nor sabotage that led to the downfall of Berlin, but the disorganization of the command system, brought about by Hitler. Neither resigned obedience nor attempts by individuals to act responsibly and intelligently on their own initiative could have availed.

CHAPTER 4. THE DEFENSE POSITIONS

I. GENERAL

SKETCH 3. DEFENSE INSTALLATIONS

1. The Geographical Situation. The only major natural barriers which effectively protect the city of Berlin are the Havel lakes to the west and the Dahme River and the Mueggelsee to the southeast. Because of their narrow width the Teltov Canal to the south and the Spree River and the Landwehr Canal in the heart of the city are only minor obstacles. Protection against tanks is offered by the canals and irrigated fields which lie to the northeast of the city. Thus in the south and north and along most of its eastern flank the city is almost completely open to attack.

Extending around Berlin at a distance of 30-50 kilometers to the south, east, and north is a wooded area in which lakes, rivers, and canals constitute impediments to advancing troops. Of particular importance i6 the belt of woods and lakes to the east which runs past Koenigswusterhausen, Erkner, and Tiefensee toward the old Oder River near Bad Freienwalde.

A close-knit network of roads surrounds Berlin. The open terrain consists mostly of sandy, easily passable ground. A covered approach to the outskirts of the city is facilitated by patches of woods to the southeast and northeast and in most other places by extensive parks.

Within the city limits the burned-out ruins and fields of debris resulting from bombing raids favored defensive action.

2. Tactical Considerations. At first Berlin was to be defended at the Oder. Because all troops were needed there, no thought was given to plans for a protracted defense in the wooded area mentioned above. Such a position would have extended over more than 200 kilometers. Nevertheless, the belt of woods and lakes from Erkner to Tiefensee was prepared as a position for defense against an attack from the east.

At a distance of about thirty kilometers beyond the city perimeter an "obstacle ring" was to delay the enemy's approach. All larger localities between the obstacle ring and the city perimeter were to become tactical strong points.

The actual defense was to be carried out along the perimeter itself, full use being made of available obstacles. Even this position extended along a circumference of about one hundred kilometers. At least one hundred battle-worthy divisions would normally have been required to occupy it, whereas the Commander of the Defense Area had. at his disposal as infantry only 60,000 Volkssturm troops, one-third of whom were unarmed and two-thirds poorly armed. In addition there were between twenty and thirty artillery batteries and the city's permanent antiaircraft units.

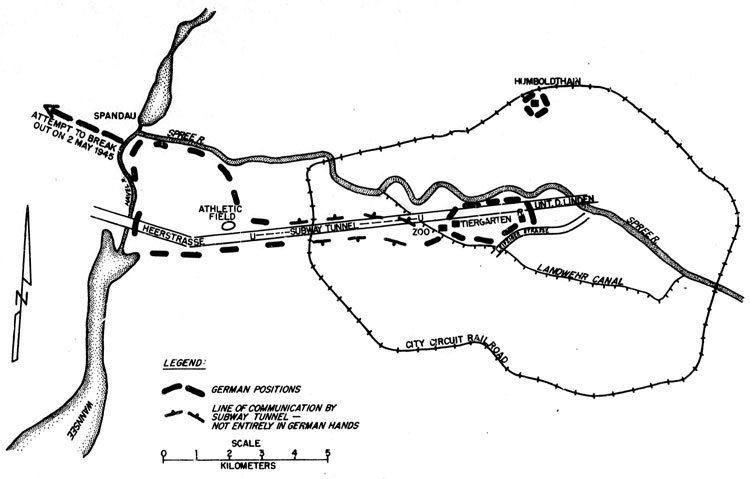

Since Berlin was to be defended to the last house even after the loss of the perimeter position, it was also necessary to make defense preparations in the heart of the city. The city circuit railroad, which extended over a distance of thirty-five kilometers, offered a coherent line for this purpose. Still farther towards the city center, the island formed by the Landwehr Canal and the Spree River was foreseen as a defense position. If the enemy penetrated even here, then individual buildings, such as the Reich Chancellery, the Reichstag Building, the Bendler Block, and the air raid shelters, were to be defended.

3. Manpower and Means Available for Construction. Engineer forces subordinate to the Commander of the Defense Area were commanded by Colonel Lobeck. Engineer officers and engineer detachments were assigned to the sector commanders to supervise the construction workers and carry out demolition measures. Since only one construction engineer battalion was available, General Reymann ordered two engineer battalions to be organized from Volkssturm troops trained for that purpose.

The construction manpower on hand consisted of some units of the Todt Organization and the Labor Service, the Volkssturm, and the civilian population. The total number of persons working on the positions amounted at the most to 70,000 on any one day. While that number seems small considering that Berlin contained over three million inhabitants, it must be remembered that until the very last the countless factories and workshops in and around the city were still working day and night. Moreover, the workers had to be transported to and from the construction areas every day. The city and suburban rail transit systems were already overtaxed and were often disrupted by the constant bombing raids. Many distant construction areas could not even be reached by rail, and gasoline for busses and trucks was not available. Efforts were made to utilize personnel from enterprise located near the positions under construction. Only the Todt Organization and Reich Labor Service were well equipped. Most of the construction workers had to furnish their own tools. Small quantities of entrenching equipment could be obtained from the Rehagen-Klusdorf Engineer Depote. At first a few trenches and antitank ditches were dug with power shovels, but their use soon had to be discontinued because of lack of fuel.

Owing to the pressure of time and the shortage of building equipment and materials, it was out of the question to construct bunkers of reinforced concrete. Only very small quantities of mines and barbed wire were on hand.

The construction plans which could actually be carried out were limited largely to the following: Along both the outer and inner ring, trenches with machine gun emplacements and splinterproof shelters or adjoining underground rooms were dug. For the most part the positions had no depth. Streets in all sectors of the city were blocked by antitank obstacles. Antitank ditches were dug at a few important points along the outer ring. At main roads which might be used for incursions into the city a few mines were laid and barbed wire entanglements strung. Otherwise these were completely lacking. Rear and shift positions were built in many places between the city perimeter and the inner defense ring. Most of these detached positions resulted from the personal initiative of local Party leaders and showed a lack of coordinated planning and competent execution.

II. THE INDIVIDUAL POSITIONS

1. Outpost Area and Forward Defense Position. Building the obstacle ring consisted merely in erecting road blocks at suitable points, mostly in inhabited localities, In conjunction with these, foxholes were dug as protection against tanks. Each road block was guarded by a security detachment of from thirty to forty Volkssturm men armed with infantry and antitank weapons.

All larger localities behind this obstacle ring were designated as tactical strong points, which were to be defended to the last man. Since this measure could have had no tactical value, General Reymann by repeated protests to Hitler succeeded in having the plan abandoned.

Antitank obstacles were set up in every conceivable (and even inconceivable) place. Many of these hindered German troop movements and often had to be removed.

Few of the outpost area installations had any practical value. From the beginning the weak Volkssturm units were without heavy weapons, means of reconnaissance, and common leadership. They even lacked contact with one another. Only In exceptional instances did they delay the approach of the Russians for even a few hours, In most cases there was probably no defensive action at all, especially since the obstacles could usually be bypassed.

The forward defense position was inherently strong, since it took advantage of a favorable sector of terrain. The constructed defenses, however, were only those found in an ordinary field positions. Luftwaffe personnel who had been made available in large numbers by Goering at the beginning of April, but who were unarmed and untrained in ground warfare, were assigned to hold this position, supplemented by Volkssturm troops.

This force apparently disintegrated at the approach of the Russians; there is no mention in any report of serious fighting for the forward defense position. Evidently the thirty battalions dispatched from Berlin on 21 April in the direction of this position were unable to reach it before the Russians, since on 22 April columns of Red troops were found west of this line, advancing along a broad front. The forward defense position should have delayed the attacker for some time. This was not the case largely because of confusion in the chain of command. At the very moment that the advancing enemy reached this position, Hitler ordered the LVI Panzer Corps to take the offensive. All of its forces were massed for attack on both sides of the Berlin-Kuestrin railroad line, while to the north the Russians had a free hand. If the Ninth Army had been free to make its own decision, the LVI Panzer Corps would probably have been used to defend the forward defense position along a broad front. At the same time the right half of the Ninth Army which had not been attacked, would have withdrawn from the Oder, sending as many of its elements as possible into the defense position to reinforce the hard-fighting left wing.

The Commander of the Defense Area, for his part, was unable to hold the forward defense position with the weak forces at his disposal. Its quick collapse resulted largely from the lack of a realistic and uniform command system.

2. Position Along the City perimeter. This position constituted the main line of resistance of the Berlin strongholds. It consisted largely of a continuous trench, with elaborations on the eastern and western flanks, where In both cases a second position was built behind the first.

The layout of the position was as follows: In the south, it ran first along the north bank of the Teltow Canal; then south of the canal from Llchterfelde to Johannistal. In the east the first position extended on either side of the Mueggelsee and then circled around Mahladorff, the second position followed the Gruenau - Herzberg railroad line. In the north, the line of defenses ran below the irrigated fields along the northern perimeter of the city past Weissensee and Niederschoenau, then parallel to the North Moat (a very minor obstacle) to the Tegeler See. In the west, it extended along the east bank of the Tegeler See and the Havel; the first position then continued along the western perimeter of the city past Spandau, Seeburg, Gross-Glienicke, and Sakrow (for the protection of the Gatov Airfield), and the second position along the east bank of the Havel lakes.

Behind this line lay the gun emplacements of the twenty permanent local batteries and the antiaircraft artillery that was not permanently emplaced.

The following excerpts from reports by men who took part in the fighting illustrate the condition of Berlin's defenses at the time contact was first made with the advancing enemy. Each report describes a company or battalion sector in one of the city's four quarters.

a. Teltow Canal near Klein-Machnov; report of 1st Lieutenant von Reuss, commander of a Volkssturm platoon:

Preparations for defense of the Teltow Canal included the construction of works along the northern bank and the organization of a bridge demolition team. A fire trench was laid out at a varying distance from the canal and machine gun emplacements were established 500-600 meters apart. Each emplacement was connected with a protected shelter by means of a communications trench.

The trenches led partly through marshy terrain and interfered greatly with troop movements. A machine gun emplacement, protected with cement slabs, was constructed on the grounds of an asbestos factory. There were no artillery emplacements to the rear, although two antiaircraft guns had been brought into position. A rocket projector had also been set up.

The only complete unit which figured in this sector was the Klein-Machnow Volkssturm Company, which was joined by a few stragglers from the Wehrmacht.

The platoon was armed with only one machine gun, of Czech manufacture, which went out of action after being fired only once. In addition, there were rifles of various foreign makes, including even some Italian Balilla rifle.

Of further interest is the fact, mentioned later in the report, that on the evening after the first encounter with the enemy the platoon adjacent to that of the writer went back to its quarters for the night and reappeared the next morning. Since the Russians attacked weakly here, the Volkssturm troops were able to hold this sector for two days.

b. Sector east of Friedrichshagen (Muegglsee); report of Master Sergeant Guempel, fortifications construction superintendant:

Sergeant Guempel and ten men from the cadre of the replacement battalion of the Gruenheide administrative unit were responsible after the middle of February for directing the construction of fortifications east of Friedrichshagen and to the north of the Mueggelsee, a sector about three kilometers in width. Manpower was recruited from the Friedrichshagen population and from workers in the local factories. As many as five hundred workers a day were provided, continuous trench was dug and permanent emplacements were prepared. The construction of shelters was begun under supervision of a building expert from Friedrichshagen, although none were completed before the start of the fighting.

It had been planned to occupy the position with a force of 250 men, comprising elements of the replacement battalion and Volkssturm troops. With the approach of the Russians, the force holding the position disintegrated and the position was left virtually unmanned. Only the battalion commander and about twenty-five men offered resistance. The defenders were overcome, after which Sergeant Guempel and his group tried to collect stragglers.

c. Sector east of the Tegeler See; report of Major Schwark, commander of a plant protection battalion:

The position sector was bounded on the left by the northern tip of the Tegeler See, from where it extended to the right along the Tegeler Run, also called the North Moat. This moat held little water and was more a line along which to build fortifications than an actual obstacle itself. The position consisted of a shallow fire trench, without barbed wire or mines.

The battalion commander had been familiarized with the terrain and had participated in two map exercises. The position was occupied by the plant protection battalion, which comprised four under strength companies armed with rifles, hand grenades, and a few Panzerfaeuste. Most of the men were veterans of World War I and because of their service with plant protection units were accustomed to order and discipline. The Russians avoided a frontal attack, using infiltration instead, especially at night; such tactics were aided by the poor visibility afforded by the terrain. Particular trouble was caused by roof-top snipers in front of and behind the German lines. Nevertheless, it was still possible to keep the men together. When the battalion was almost surrounded after three days of fighting, it withdrew and occupied a new position in the Wittler bakery plant, where the writer was seriously wounded.

d. Gatow sector; report of Major Komorowski, commander of a composite battalion:

The battalion, as part of a regiment, defended a section of the first position, located along the western perimeter of the Gatow Airfield, which was to be protected against attack from the west. If the first position were lost, the troops were to cross the Wannsee in boats lying in readiness in order to occupy the second position along the east bank of the lake.

The position consisted of a well-built, continuous trench. The battalion was composed of construction and Volkssturm troops, none of whom had had combat experience. They were armed with captured rifles and a few machine guns, and had only a limited supply of ammunition. The infantry was supported by an 88-mm antiaircraft gun battery and a heavy infantry gun platoon, although the latter unit had never fired its weapons. Support was als0 received from the garrison of the Zoo Flak Tower. On the evening of the first day of battle all the Volkssturm troops deserted, and the gap was filled only by recruiting stragglers. In two days of fighting all the defenders were either killed or captured.

The position along the city perimeter, which formed the main line of resistance of the Berlin stronghold, had little over-all value. For long stretches it consisted only of a fire trench, without support in front or behind. Nowhere was the position manned by well coordinated, battle-tried troops. The loosely organized, makeshift units were inadequately armed and varied greatly in their will to fight. It is astounding that in many places the Russians allowed themselves to be held back for several days by the resistance of a few valiant men. Wherever the enemy made a serious effort to push forward, the position fell with the first onslaught. The enemy did not take full advantage of such successes, however, but changed over to a hesitant and methodical attack procedure. As a result, the various intermediate and switch positions halted their advance time and again. Once past the outer defenses, the enemy encountered the experienced and well-armed troops of the LVI Panzer Corps, who made full use of the prepared positions and the terrain in between to offer strong resistance.

3. Position Along the Town Circuit Railroad and the Innermost Defenses. The value of the town circuit railroad lay in its offering the defenders a clear line of defense. The fortifications constructed here were similar to those along the perimeter of the city, although because of the hard soil continuous trenches generally had not been dug. The position consisted primarily of permanent individual emplacements for three or four men. Plans had also been made to fortify the streets behind the position; this was done according to available means and individual initiative. These preparations are described in a report by a former Volkssturm battalion commander, Heinrich Bath:

The Volkssturm battalion, organized in Charlottenburg-West, was to serve as a reserve for another Volkssturm battalion, which was drawn up along the city circuit railroad. Defense fortifications were to be built along the street behind the forward battalion, The reserve battalion had a strength of eight hundred men. Weapons and tools, especially entrenching tools, were lacking. Many of the men had no proper work clothes. The battalion was under the orders of Party District Headquarters I on Wittenberg-Platz. At the same time, the battalion was also subordinated to a military sector headquarters. This situation often caused confusion in command.

First of all, fixed and movable tank obstacles were constructed. The three main thoroughfares in the battalion sector were provided with stationary concrete obstacles with movable middle sections to allow the passage of streetcars and other vehicles. The openings were closed after dark and were always strongly guarded. At night all traffic was suspended. Side streets were provided with stationary obstacles which completely blocked vehicle traffic and left only a narrow opening on one side for pedestrians. These obstacles — some twelve barricades, each three meters high - consisted of beams and steel girders rammed into the street bed and covered with heaps of rubble.

To cover the streets, machine-gun emplacements were set up on upper stories. Passageways were constructed from the cellars into the street as posts from which to attack tanks with Panzerfaeuste. Cellars were converted into shelters and connected with one another so that troop movements could be carried out under cover. The roofs were also prepared for battle; sniper posts were set up and passages for access were devised.

As a result of the extensive construction work training was largely neglected, although lectures were given to bolster morale.

Shortly before the battle the battalion received about a hundred rifles. During the fighting only about sixty men remained at their posts, the greater number having returned to their homes.

Many sections of the position along the city circuit railroad, the inner defense, and the numerous switch positions, were made ready in the manner described above. The extent of the work accomplished depended entirely on the competence and initiative of those directing the construction. Works of this kind in a large city make possible very strong resistance, provided they are occupied by troops determined to fight. In Berlin some positions were stoutly defended, while others fell into Russian hands almost without a struggle.

4. The Flak Towers. The Zoo, Humboldthain, and Friedrichshain flak towers, as well as the flak control tower (without guns) had been built during the period of the air attacks. They served as antiaircraft gun emplacements and air defense command posts and at the same time as giant air raid shelters for protection of the populations With their own light and water installations and large supplies of ammunition and food, these structures were capable of sheltering fifteen thousand persons in addition to the military garrison. During the fighting they were filled with wounded, deserters, and civilians, so that their normal capacity was probably far exceeded.

Because of their location and construction, no thought had been given to utilizing the flak towers in the ground fighting. No embrasures existed and no entrance defenses had been constructed. The surrounding area fell within the blind angle of the guns emplaced on the platforms and terraces of the towers. Nevertheless, the towers held out very well in the ensuing battle. The antiaircraft artillery played a successful part in the ground fighting, even in the suburbs of the city. None of the towers was pierced by bombs or direct hits by heavy artillery. In attacking the Zoo flak tower, Russian tanks attempted to fire into the windows, which were protected only by sheets of armored plates. Only a few lower-story windows were hit; the enemy guns could not be elevated to reach the upper stores. In the rooms where shells exploded, heavy casualties were caused by flying fragments of concrete, since the walls had not been faced.

The close defense of the towers was conducted from field positions set up around them. The Humboldthain and Friedrichshain flak towers held out for days after being completely surrounded. The Zoo flak and flak control towers also did not surrender until after the general capitulation. At that time the antiaircraft artillery of the Zoo tower was still intact, whereas that of the Friedrichshain tower had been put out of action by bomb hits0 The Friedrichshain tower surrendered as early as 30 April, partly because in that sector the Russians drove the German population before them as they attacked.

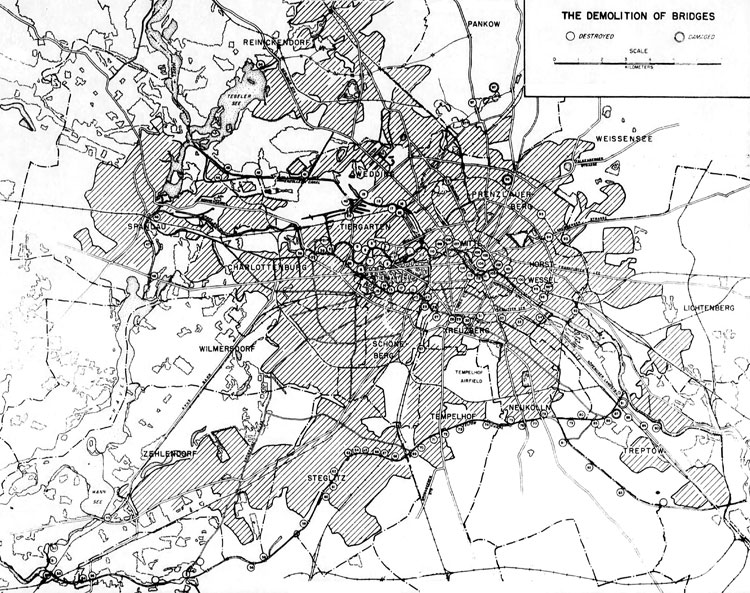

III. PLANS FOR DEMOLITION

1. Bridges. Preparations had been made to blow up all bridges and numerous overpasses in Berlin. Bitter quarrels subsequently arose between those who, like the Commander of the Defense Area, advocated military necessity, and those who wished to prevent the demolitions in the interest of the population. Reich Minister Speer, especially, did his utmost to moderate the extent of the destruction. The question was vitally significant not only because of the need for traffic routes, but above all because the water and sewerage mains lay under the bridges. Speer succeeded in obtaining from Hitler an order whereby a number of particularly important bridges were to be saved.

The degree to which the demolitions were carried out during the battle varied. Some of the bridges were only damaged, so that they could still be crossed by infantry and, after repairs, by tanks and other vehicles.

According to an investigation made by Colonel Roos, of the 248 bridges in Berlin 120 were destroyed and 9 damaged.

SKETCH 4. THE DEMOLITION OF BRIDGES

Only a few of the overpasses were blown up, apparently for lack of explosives.

2. Subway and City Transit Line Tunnels. The network of subway and city transit line tunnels could be used for covered movements by both friendly and enemy troops. In case of necessity they could be blocked at various points by setting off explosive charges that had already been planted.

In the course of the battle the city transit line tunnel under the Landwehr Canal was blown up, after which it filled with water. It could not be determined at whose orders this measure was carried out. With the blowing up of the Ebert Bridge (east of the Vleidendamm Bridge) the city transit line tunnel there was also destroyed, although this was apparently unintentional. Because of these and other explosions, water flowed into large parts of the subway and city transit line tunnels in the heart of the city.

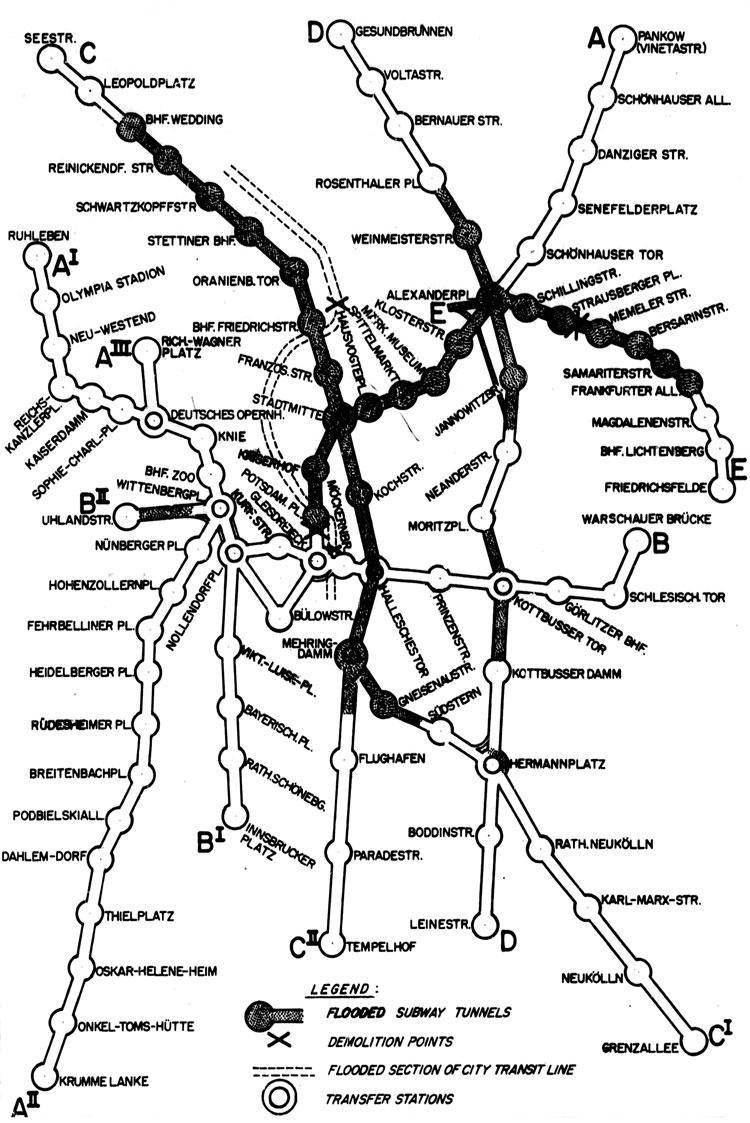

SKETCH 5. THE FLOODING OF SUBWAY TUNNELS

It could not be proven that any appreciable loss of life resulted from the flooding of these tunnels, but it can be seriously doubted that it was justified by military necessity.[*]

[* - It was common talk among the Allied occupation forces that hundreds of bodies were later recovered from these tunnels0 (Editor)]