Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

THE GERMAN CAMPAIGN IN THE BALKANS (SPRING 1941)

A MODEL OF CRISIS PLANNING,

BY GENERAL-MAJOR MUELLER-HILLEBRAND

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF MILITARY HISTORY

FOREWORD

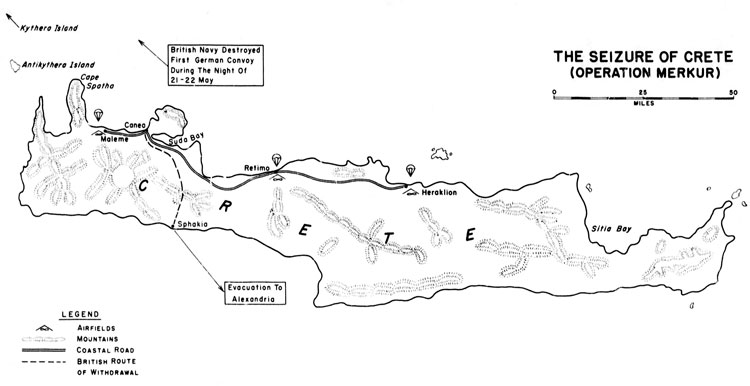

The tentative study, '"The German Campaigns in the Balkans (Spring 1941)," is an account of a Nazi blitz in which political machinations and military policy were synchronized and utilized to insure rapidity in decision, in planning, in concentration, end in operations. The campaigns culminated in the largest mass airborne attack that had ever been launched up to that time. The success of this action captivated the minds of Allied military men and probably helped create the very considerable airborne force organized by Great Britain and the United States. Little did they know at the time of the serious loss sustained by the Germans who never again employed any considerable number of airborne troops in an air landing.

It is believed that this study, although tentative, will prove of interest and of value to all serious military students.

ORLANDO WARD

Major General, USA

Chief, Military History

Washington 25, D.C.

August 1952

PREFACE

The purpose of this tentative study is to describe the German campaigns in the Balkans and the seizure of Crete. It will be perfected, as source material and comments become available, and finally published as a pamphlet. It is believed that the study, the first of a series dealing with large-scale German military operations in Eastern Europe, will reveal many lessons of value to military students. Other studies such as The German Support of Finland, The Axis Campaign in Russia, 1941-45: A Strategic Survey, and German Army Group Operations in Russia will follow.

German victories over Poland, Denmark and Norway, and the Low Countries and France and their ally Great Britain were gained cheaply by blitz tactics. In the broadest sense, however, those victories were merely tactical. They only tended to clear the foreground and to bring the European Axis fare to face with political and strategic al problems of ever-widening range and complexity. To an aggressor these problems could only be solved by force. Relieving himself unable to act decisively in the west, Hitler sought to resolve his problem to the east, but simultaneously was pulled to the south by Mussolini's rashness and by the peculiar situation existing in the Balkans. At the same time he was forced to consider his northern flank and the support of Finland, which had so heroically taken up arms against Russia in defense of its liberty.

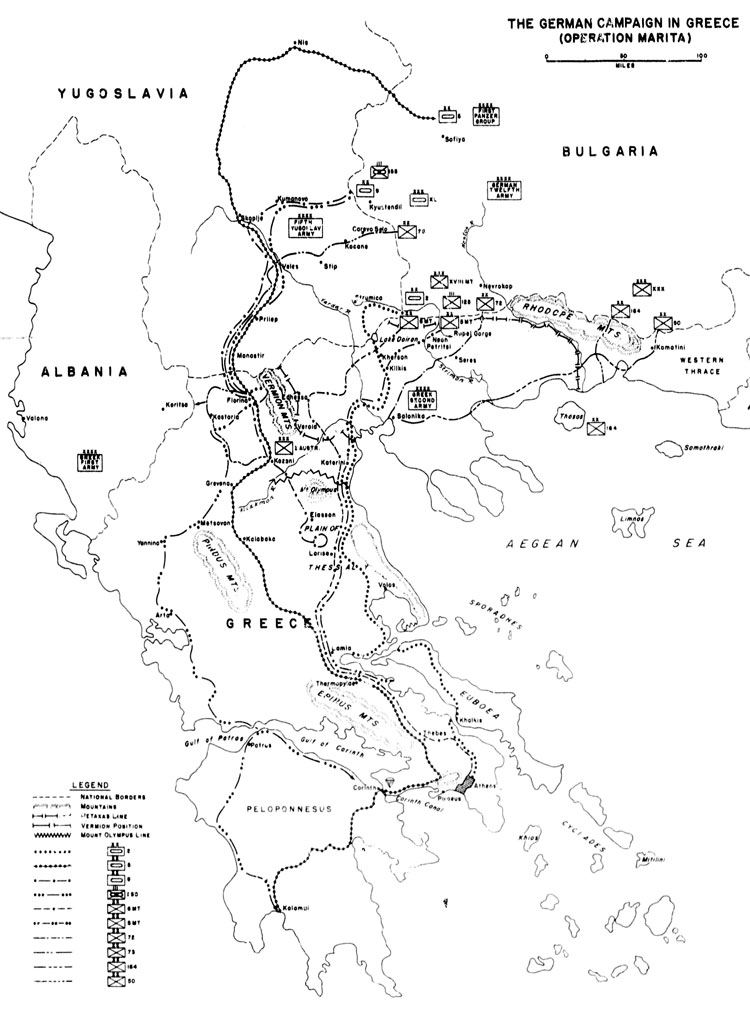

From the point of view of German strategy, the Balkans posed a difficult problem which had to be resolved before action could be taken against the USSR. Hitler hoped to attain his aim by diplomacy and to a certain extent did. But in the end the maneuvering of Great Britain and the military failures of Italy compelled him to use force. The campaign that followed was based on severing the lines of communication between Yugoslavia and Greece by an armored thrust from the Bulgarian border in the direction of Albania. Once the Belgrade - Salonika railway was cut, Yugoslavia was isolated. After that, the tactical operations amounted to little more than police action. The culmination of the campaign was the German airborne attack upon the island of Crete which made such a profound impression upon Allied military men. In this account it is seen through German eyes.

"The Gorman Campaigns in the Balkans" is written from the German point of view and is based almost entirely on original German records and postwar manuscripts prepared by former German officers who participated in the operations. The lessons and conclusions following each narrative have been drawn from the same German sources. (These records and manuscripts are listed in Appendix III.) Material taken from U.S. and Allied sources has been integrated into the text, but specific cross references have bean made only in those instances where the sources deviate from the German documents.

The work of preparing this study, which consisted of translating several basic German monographs, performing additional research, and then rewriting the monographs with an eye for continuity and correct factual data, was done in the Foreign Studies Branch, Special Studies Division, Office of the Chief of Military History. In the process of presenting the material, every effort has been made to give a balanced account of German strategy and operations in the Balkans during the spring of 1941.

The German authors had access to selected documents bearing on the subject. Among the authors were: Dr. Helmuth Greiner, Gen. Burkhart H. Mueller-Hillebrand, arid the late Gen. Hans v. Greiffenberg.

The German studies and documents were translated and edited and then expanded by material drawn largely from German and British sources by Mr. George E. Blau, assisted by Lt. Gerd Haber and Mrs. Olga V. Fuhrman. The maps were prepared by Mr. Frank Vogel.

P. M. ROBINETT

Brigadier General, USA, Ret.

Chief, Special Studies Division

PART ONE. THE MILITARY-POLITICAL SITUATION IN THE BALKANS

(October 1940 - March 1941)

During the latter half of 1940 the Balkans, always a notorious hotbed of intrigues, became the center of conflicting interests of Germany, Italy, Russia, and Great Britain. From the beginning of World War II Hitler had consistently stated that Germany had no territorial ambition in the Balkans. Because his primary interest in that area was of an economic nature — Germany obtained vital oil and food supplies from the Balkan countries — he was prepared to do his utmost to preserve peace in that part of Europe. For this reason he attempted to keep in check Italy's aggressive Balkan policy, to satisfy Russian, Hungarian, and Bulgarian claims to Romanian territory by peaceful means, and to avoid any incident which might lead to Great Britain's direct intervention in Greece. It was no easy task to synchronize so many divergent political actions at a time when Germany was preparing the invasion of the British Isles and later planning as alternate measures the capture of Gibraltar, the occupation of Egypt and the Suez Canal, the seizure of unoccupied France, and — last but certainly not least — the attack on Russia. By 1940 Hitler had refined the process of bloodless aggression to a high degree of efficiency. As the immediate political means in the Balkans, he used the customary fifth-column tactics, by which the Germans infiltrated the internal structure of one Balkan state after another. As soon as the political machinery of a country was sufficiently paralyzed, its government was forced to adhere to the Tripartite Pact, which had been signed by Germany, Italy, and Japan on 27 September 1940 (see Appendix II, Chronological Table of Events). Adherence to the pact was the symbol of admission to the ranks of satellite states; it also meant the loss of that country's independence. In general, shortly after the new member of the pact had signed, a German military mission crossed its border and took over communications, airfields, and the responsibility for the internal security of the country.

MAP 1. GENERAL REFERENCE MAP

For a better understanding of the military operations that took place in the Balkans during the spring of 1941, it is necessary to analyze the political events that led to the outbreak of hostilities.

Chapter 1. The Great Powers

I. Germany

After the signing of the Franco-German armistice on 22 June 1940, Hitler believed that Great Britain would be prepared to come to an understanding since British forces had been driven off the Continent and France had been subdued. However, soon after his return to Berlin on 6 July it became evident that the British Government, far from entertaining any ideas of reconciliation, was determined to carry on the war. German preparations for the invasion of Great Britain were pushed with vigor. Hitler's speculations as to the reasons for Great Britain's stubborn refusal to come to terms led him, as early as 21 July 1940, to the belief that Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill hoped for Russia's entry into the war against Germany. On 31 July Hitler mentioned for the first time since the conclusion of the Russo-German treaty that he would be forced to invade Russia and that the attack would have to be launched in the spring of 1941. Ho requested the Army General Staff to study the various aspects of a campaign against Russia and directed that, in its organizational planning for the future, the Array must not lose sight of the possibility of a war with the Soviet Union. This request was subsequently repeated during the discussion of other plans.

After the failure of the air offensive against the British Isles Hitler decided, on 12 October 1940, that the invasion of England would be postponed until the spring of 1941. With the plans for a direct invasion of England shelved, he tried to find a way to defeat Great Britain without attempting a cross-Channel attack.

For this purpose he ordered the Army to draw up plans for the capture of Gibraltar on the assumption that Spain would permit the passage of German troops through its territory. Moreover, Italy planned to invade Egypt, at the beginning of August 1940, by a series of offensive operations launched from its Libyan bases. In Hitler's opinion, the Italians would net be able to launch the final decisive drive into the Nile delta before the autumn of 1941. German forces were to participate in the final stage of the operation, and the Army High Command was instructed to prepare the necessary forces — approximately one panzer corps — for desert warfare in the tropical climate. Since the Germans lacked experience in this type of warfare, appropriate motor transportation, equipment, ammunition, and clothing had to be developed and produced.

While Germany was preparing to intervene at both ends of the Mediterranean, peace in the Balkans had to be maintained at any cost. Hitler believed that this could best be achieved by forcing Romania to cede the territories claimed by its neighbors and by lining up the Balkan countries on the Axis side.

The dismemberment of Romania was accomplished in successive stages. Russian occupation of Besserabia and northern Bukovina at the end of June 1940 gave added impetus to Hungarian and Bulgarian revisionist claims. The Romanian Government therefore issued orders for general mobilization to defend its territory. Germany and Italy had to use all their influence to prevent an armed conflict. Hitler's intervention in favor of Bulgaria led to the cession of the southern Dobrudja by Romania on 21 August 1940. By then only the Hungarian claims remained to be settled. This was achieved by the Vienna Arbitration Award, which took place on 30 August. Romania was to yield to Hungary one third of Transylvania, that is, some 16,600 square miles with a population of 2.4 million inhabitants. Even more important than the partition of Transylvania, however, was the guarantee given by the Axis Powers to defend the territorial integrity of what was loft of Romania. Thin guarantee was clearly directed against the Soviet Union. In Romania the various territorial concessions caused a political overturn, bringing Gen. Ion Antonescu to power. Upon the general's request the first elements of the German military mission entered Romania on 7 October. German Army and Luftwaffe units were to protect the oil fields, train and/reorganize the Romanian military forces, and prepare the ground for a possible attack on Russia from Romanian bases.

II. Italy

Neither the Italian nor the Russian Government received official notification of the entry of German troops into Romania. This was all the more surprising to Mussolini because Italy and Germany had given a joint guarantee to Romania, Mussolini was very indignant about being faced with a fait accompli and decided to pay-Hitler back in his own coin by attempting to seize Greece without notice to Germany,. Mussolini 9xpected that the occupation of Greece would be a mere police action, similar to Germany's seizure of Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939. On two preceding occasions Hitler had agreed that the Mediterranean and Adriatic were exclusively Italian spheres of interest. Yugoslavia and Greece were supposed to be zones of interest in which Italy could adopt whatever policy it saw fit, There was no reason why the man who had revived the Mare Nostrum concept should hesitate to demonstrate to the entire world that his twentieth century Romans were as superior to the modern Greeks as their ancestors had been to the Greeks 2,000 years ago.

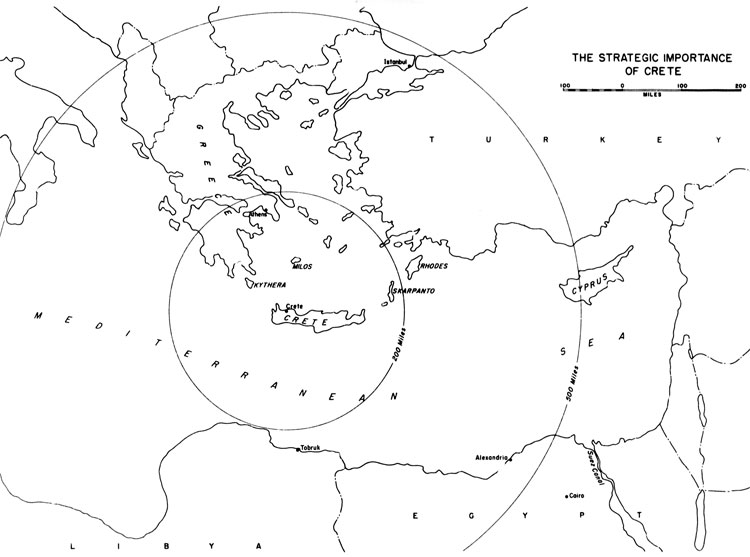

Although not officially informed, the German military and political leaders seem to have been aware of Italy's intention to attack Greece. What enraged Hitler was that his repeated, pointed statements of the need of peace in the Balkans had been ignored by Mussolini. The attack was launched on 28 October, and the Italians' immediate lack of success only served to heighten Hitler's displeasure. In the opinion of the German military, any campaign in the Balkans would have to be executed in a manner similar to the one applied by the Germans in the campaign in Norway. The strategically important features would have to be seized in blitzkrieg fashion. In the Balkans these points were not situated along the Albanian border but in southern Greece and on Crete. The Italian failure to capture Crete seemed a strategic blunder, since British possession of the island endangered the Italian lines of communication to North Africa and assured Greece of a steady flow of supplies from Egypt. Tn any event, on 4 November Hitler ordered the Army High Command to initiate preparations for military operations in the Balkans.

The German displeasure at the ill-timed Italian attack on Greece found its expression in a letter Hitler addressed to Mussolini on 20 November 1940. Among other things, he stated:

I wanted, above all, to ask you to postpone the operation until a more favorable season, in any case until after the Presidential election in America, In any event I wanted to ask you not to undertake this action without previously carrying out a blitzkrieg operation 6n Crete. For this purpose I intended to make practical suggestions regarding the employment of a parachute and of an airborne division.

In his reply of 22 November Mussolini expressed his regrets about the misunderstandings with regard to Greece. The Italian forces had been halted because of bad weather, the desertion of nearly all the Albanian forces incorporated into Italian units, and Bulgaria's attitude, which permitted the Greeks to shift eight divisions from Thrace to Albania.

Hitler's decision to intervene in the military operations in the Balkans was made on 4 November seven days after Italy had attacked Greece through Albania and four days after the British had occupied Crete and Limnos. He ordered the Army General Staff to prepare plans for the invasion of northern Greece from Romania via Bulgaria. The operation was to serve the double purpose of depriving the British of bases for future ground and air operations across the restive Balkans against the Romanian oil fields and of assisting the Italians by diverting Greek forces from Albania.

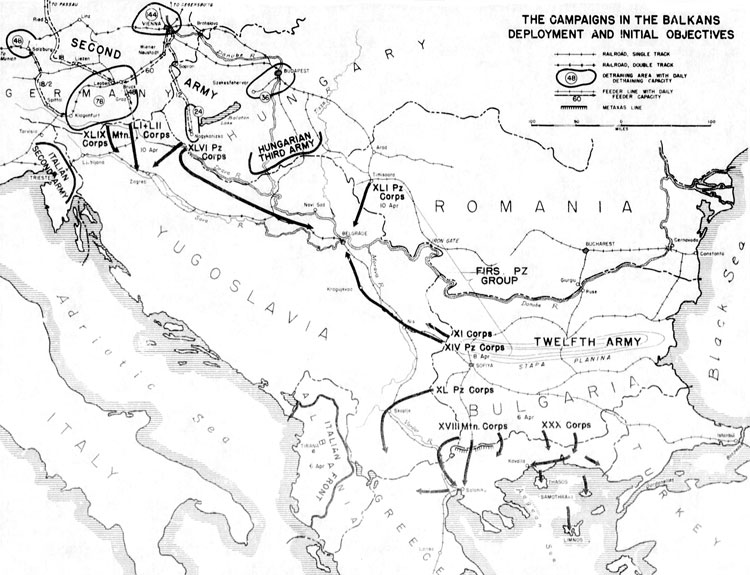

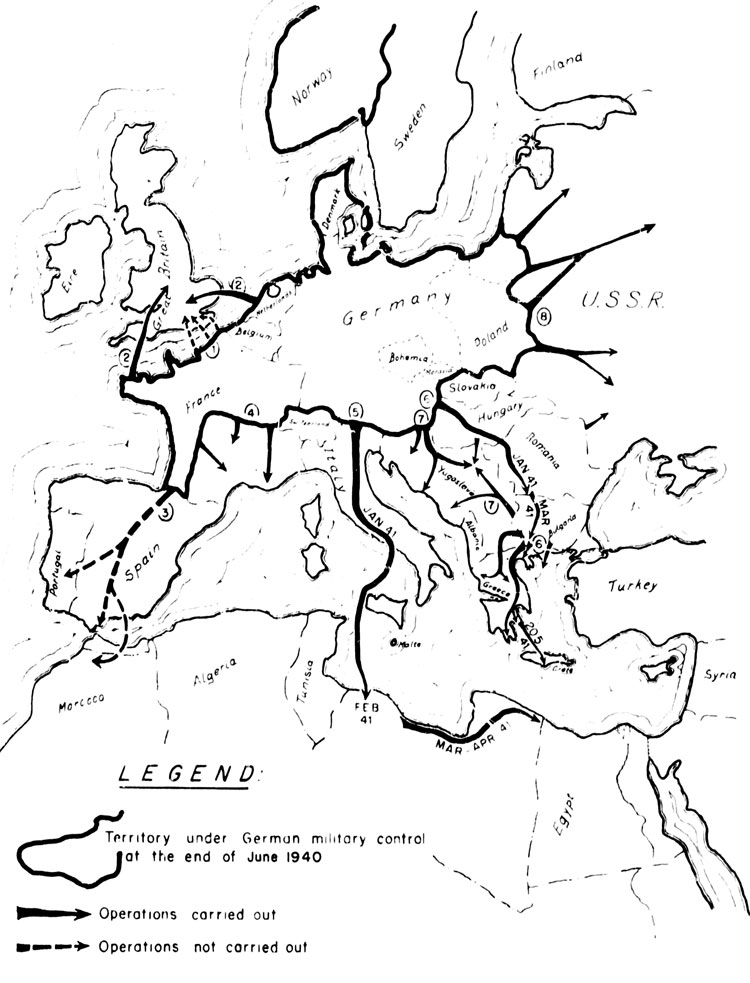

The plans for this campaign, together with the projects involving Gibraltar and North Africa, were incorporated into a master plan to deprive the British of all their Mediterranean bases. On 12 November 1940 the Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 18, enumerating to the three services the following objectives (Map 2):

a. The capture of Gibraltar via Spain;

b. The seizure of Egypt and the Suez Canal from Libyan bases;

c. The invasion of Greece from Bulgaria; and

d. The speedy seizure of unoccupied France at a moment's

notice.

MAP 2. GERMAN OPERATIONS AND PLANS

July 1940 - March 1941

(1) INVASION OF GREAT BRITAIN:

First discussion of the plan-----------------------Toward the end of June 1940

Order to Start preparations------------------------16 July 1940

Intended start of the operation-----------------September 1940

Cancellation of the operations order-----------12 October 1940

(2) INCREASE AIR AND NAVAL WARFARE AGAINST ENGLAND

First discussion of the plan----------------------July 1940

Order to start preparations-----------------------1 August 1940

Start of the operations------------------------------8 August 1940

(3) GIBRALTAR:

First discussion of the Plan----------------------September 1940

Order to start preparations-----------------------12 November 1940

Intended start of the operation-----------------January 1941

Cancellation of the operations order —------8 December 1940

(4) SEIZURE OF UNOCCUPIED FRANCE:

Order to start preparations------------------------12 November 1940

Execution of the operation-----------------------November 1942

(5) PARTICIPATION IN ITALIAN OFFENSIVE TOWARD EGYPT (SUEZ CANAL)

Order to start preparations.----------------------12 November 1940

Intended start of the operation-------------------Autumn 1941

( Actually, operations in support of the Italians started already at an earlier moment, but with defensive objectives)

(6) OPERATION MARITA:

First discussion of the plan----------------------4 November 1940

Order to start preparations-----------------------13 December 1940

Start of the operation:--------------------------------6 April 1941

(7) OPERATION 25:

First discussion & order to start

preparations----------------27 March 1941

Start of the operation-------------------------------6 April 1941

(8) OPERATION BARBAROSSA

First discussion of the plan-------------------------End of July 1940

Order to start preparations------------------------18 December 1940

Intended start of the operation----------------15 May 1941

Start of the operation---------------------------------22 June 1941

The operations against Gibraltar and Greece were scheduled to take place simultaneously in January 1941, while the German offensive in North Africa was to be launched in the autumn of that year. The invasion of the British Isles was also mentioned in this directive, the target date of which was tentatively scheduled for the spring of 1941. The particular difficulty involved in the execution of some of these plans was that the German Army was supposed to conduct operations across the seas even though the Axis had not gained naval superiority in the respective areas. On 4 November even Hitler voiced doubts as to the advisability of conducting offensive operations in North Africa, since Italy did not control the Mediterranean. That these doubts were we11 founded became apparent when, on 6 November, British naval air forces inflicted a severe defeat on the Italian Navy at Taranto.

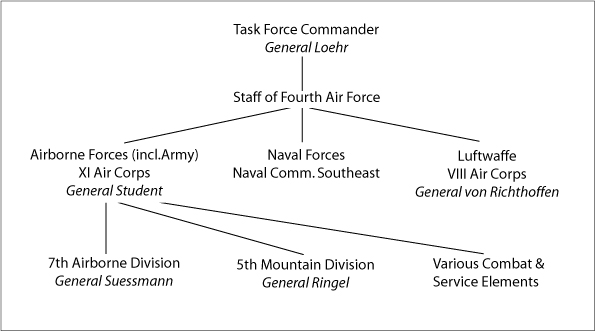

In December 1940 the German plans in the Mediterranean underwent considerable change when, at the beginning of the month, Franco rejected the plan for attack on Gibraltar. Consequently, German offensive plans in the Mediterranean had to be restricted to the campaign against Greece. For this purpose the Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 20, dated 13 December 1940, which outlined the Greek campaign under the code designation, Operation MARITA. In the introductory part of the directive Hitler pointed cut that, in view of the confused situation in Albania, it was particularly important to thwart British attempts to establish air bases in Greece, which would constitute a threat to Italy as well as to the Romanian oil fields. To meet this situation twenty-four German divisions were to be assembled gradually in southern Romania within the next few months, ready to enter Bulgaria as soon as they received orders. In March, when the weather would be more favorable, they were to occupy the northern coast of the Aegean Sea and, if necessary, the entire GreeK mainland. Bulgaria's assistance was expected; support by Italian forces and the co-ordination of the German and Italian operations in the Balkans would be the subject of future discussions. The Luftwaffe was to provide air protection during the assembly period and prepare bases in Romania. During the operation the Luftwaffe was to support the ground forces, neutralize the enemy air force, and whenever possible capture British bases on Greek islands by executing airborne landings.

Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe was to assist the Italians in stabilizing the precarious situation on the Albanian front. This was to be accomplished by airlifting approximately 30,000 Italian troops and great quantities of equipment and supplies from the Italian mainland to Albania.

Even though Hitler had decided to attack Greece, he wanted to tread softly in the Balkans so as not to expand the conflict during the winter. If Turkey entered into the war against Germany, the chances for a successful invasion of Russia would diminish because of the diversion of forces such a new conflict would involve. Moreover, at the beginning of December 1940 the British launched on offensive from Egypt and drove the Italians back to the west. Toward the end of the month the situation of the Italians in Libya grew: more and more critical. By January 19A1 their forces in North Africa were in imminent danger of being completely annihilated. If that happened, Italy with its indefensible coast line would be exposed to an enemy invasion. To avoid such disastrous developments, German air units under the command of X Air Corps were transferred to Sicily, and the movement of German Army elements to Tripoli via Italy was begun immediately. In February the first small contingents of German ground troops arrived in North Africa, and the critical situation was soon alleviated, The first German troops to arrive were elements of a panzer division under the command of General Erwin Rommel. Hitler ordered these forces to protect Tripoli by a series of limited-objective attacks thus relieving the pressure on the Italian troops. The political objective of this military intervention was to prevent Italy's internal collapse which would almost certainly result from the loss of her African possessions.

III. Soviet Union

Following the conclusion of the Russo-German alliance in August 1939, Hitler's policy was to try to divert Russian expansionist ambitions. He wanted to interest the Soviet rulers in a southeastward drive to the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea. However, there were many indications that the Russians were more interested in the Dardanelles and the Danube delta, where their political and military aspirations clashed with German economic interests. Hitler felt that the Soviet Union would take advantage of the diversion of strong German forces into distant Mediterranean areas by exerting political pressure on some of the Balkan countries.

After having forced Romania to cede Bessarabia and northern Bukovina in June 1940, the Soviet Union established itself at the mouth of the Danube, Germany's principal supply line from the east, and intensified its political activities in the Balkans, particularly in Bulgaria. By the autumn of 1940 Russo-German relations had deteriorated considerably as the result of the Vienna Award, the presence of the German military mission in Romania, and the question of threatened Soviet domination of the Danube.

These problems, as well as the entire question of the future relationship between Germany and the Soviet Union, were to be the subject of discussions between Molotov and the German political leaders during the former's visit to Berlin on 12 - 13 November 1940. All areas of disagreement were to be covered during these discussions and, if possible, the foundations for a common policy wore to be laid at the same time. It is interesting to note that German planning for the invasion of the USSR was already well advanced. A tentative plan for the Russian campaign had been submitted on 5 August and Directive No. 21 for Operation BARBAROSSA, which was issued on 18 December, was being drafted by the Army General Staff. Directive No. 18, issued on the day of Molotov's arrival in the German capital, stipulated that preparations for Operation BARBAROSSA were to be continued regardless of the outcome of the conversations.

During his conversations with Hitler, Molotov stated that, as a Black Sea power, the Soviet Union was interested in a number of Balkan countries. He asked Hitler whether the German-Italian guarantee to Romania could not be revoked because, in his opinion, it was directed against the Soviet Union. Hitler refused to give way on this question and did not commit himself on the subject of a Russian guarantee for Bulgaria, by which Molotov intended to re-establish the balance of power in the Balkans. Nor was Hitler prepared to help the Soviet Union to arrive at an agreement with Turkey regarding the settlement of the Dardanelles question. The conversations ended in a deadlock.

IV. Great Britain

During the spring of 1940 Hitler was greatly concerned over the possibility of British intervention in the Balkans. Had not Britain and France tried to establish a solid political and military front in the Balkans by concluding a series of agreements with Turkey, by trying to draw Yugoslavia into their orbit, and by consolidating their position in the Aegean? Germany's first countermeasures came in May and June 1940, when Romania was induced to repudiate the Anglo-French territorial guarantee after it had been pressured into signing a pact which stipulated that the Romanians would step up their oil production and would make maximum deliveries to the Axis Powers, British personnel supervising the operation of the oil fields were dismissed during the month of July. After the Vienna award of August 1940, Romania intended to break off diplomatic relations with Britain, but after consultation with Berlin this action was postponed because of the potential danger of British air attacks on the oil fields.

When Greece was attacked by Italy on 28 October 1940, it did not request any assistance from Great Britain, for fear of giving Hitler an excuse for German intervention. Nevertheless, the British occupied Crete and Limnos three days later, thereby improving their strategic position in the eastern Mediterranean. Since Hitler believed that this move brought the Romanian oil fields within British bombing range, he decided to transfer additional antiaircraft, fighter, and fighter-bomber units to Romania to protect the German oil resources.

When the German threat began to take more definite shape during the winter of 1940 - 41, the Greek Government decided to accept

the British offer to send air force units to northern Greece to strengthen the defense of Salonika. Early in March 1941, the British sent an expeditionary corps of some 53,000 troops into Greece in an attempt to support their allies against the impending German invasion.

However, before Germany could think of starting military operations in the Balkans, it had to secure its lines of communication. For this purpose it had to obtain firm political control over Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria, and to wrest some Important concessions and assurances from Turkey and Yugoslavia.

Chapter 2. Germany's Satellites in the Balkans

I. Hungary

The strong German forces needed for the attack on Greece could be assembled in Romania only after the Hungarian Government had granted them free passage through that country. The first step in that direction was to obtain Hungary's adherence to the Tripartite Pact. On 20 November Hungarian Premier Teleki signed the pact in Berchtesgaden, and Hitler mentioned on that occasion that he intended to assist the Italians in Greece, thus preparing the way for later demands he intended to make on Hungary.

II. Romania

During the second part of October 1940 General Antonescu made urgent requests to speed up the reinforcement of the German military mission in Romania. He explained these requests by pointing out the danger of a Russian attack on Romania. By mid-November the 13th Motorized Infantry Division (reinforced by the 4th Panzer Regiment), engineer and signal troops, six fighter and two reconnaissance squadrons, and some antiaircraft units had arrived in Romania. On the occasion of Romania's adherence to the Tripartite Fact, which took place on 23 November, Hitler informed Antonescu of his plans against Greece. Romania would not be required to lend active assistance in the attack on Greece, but v/as to permit the assembly of German forces in its territory.

Antonescu's conference with Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, the chief of OKV7 (Armed Forces High Command), which took place on 24 November, was of great importance to Romania's future. Romania's plans called for the organization of thirty-nine divisions. Motorization was the principal bottleneck but, because of Germany's shortage of rubber, Keitel could not offer Antonescu any tires. The Romanian chief of state then explained his country's plan of defense against an attack by the Soviet Union. Keitel reassured him that the German Army would lend immediate assistance to the Romanian forces in the event of a Russian invasion which, however, he considered unlikely. As a result of this conversation the German military mission was reinforced by the transfer of the 16th Panzer Division to Romania during the second half of December.

Meanwhile, the German Army General Staff had initiated the preparations for Operations MARITA and BARBAR0SSA and had drawn up the schedule for the concentration of forces and the plan of operation. On 5 December these plans were submitted to Hitler with the observation that it would not be possible to start MARITA before the snow had melted at the beginning of March. The completed plan would have to be drawn up by the middle of December since the assembly would require seventy-eight days. No definite estimate of the duration of the campaign could be given, but it would be safe to assume that it would last three to four weeks. Since redeployment of troops would require four additional weeks and their rehabilitation would add a further delays the units participating in the Balkan campaign would not be available for Operation BARBAROSSA before mid-May 1941.

Hitler believed that up to this time the threat of German retaliation had had the effect of preventing British air attacks on the Romanian oil fields from Greek territory and that probably no attacks would take place during the next months. Nevertheless, Germany would have to settle the Greek problem once and for all, unless Greece took the initiative to end the conflict with Italy and force the British to withdraw from its territory. In that event, German intervention would prove unnecessary since the issue of European hegemony would not be decided in Greece. The assembly of forces for Operation MARITA was therefore an absolute necessity and the preparations for the campaign had to be pushed so that the offensive could be launched by the beginning of March 1941.

In the meantime, late in December, the first attack echelon of the Twelfth Army, which was to be in charge of the ground forces during iteration MARITA, entrained for Romania. The heavy bridge equipment needed for crossing the Danube was shipped on the very first trains, so that it could be unloaded at the Danube wharfs by 3 January. The engineer units needed for the bridging operation had been transported to Romania during the second half of December, together with the 16th Panzer Division, They were to prepare the construction of bridges along the Danube as soon as the equipment arrived. Heavy snowfall disrupted the rail movement, and snowdrifts caused additional delays during January. Internal uprisings, which took place in Bucharest and other Romanian cities during the second half of January, were quickly suppressed by General Antonescu and therefore did not interfere with German preparations. By the end of January the Twelfth Army and First Panzer Group headquarters, three corps headquarters with corps and GHQ troops, and two panzer and two infantry divisions had arrived in Romania in full strength. In conformity with Bulgaria's request, the two panzer divisions were stationed in and around Cernavoda in northern Dobrudja, while the two infantry divisions were assembled in the Craiova - Giurgiu area in southern Romania.

III. Bulgaria

A few days after Molotov's departure, on 18 November, King Boris of Bulgaria arrived in Germany, Hitler tried to persuade him to join the Tripartite Fact and discussed with him the question of Bulgarian participation in the attack on Greece, with obvious reserve, the king merely called attention to the fact that the weather and road conditions in the Greek-Bulgarian border region would not allow for the commitment of major forces before the beginning of March. Moreover, he emphasized very strongly that it was of utmost importance for Bulgaria not to be openly involved in any German preparations until the last moment before the actual attack. Since Bulgaria's participation therefore appeared doubtful, Hitler decided that the number of German divisions would have to be increased.

In view of the appearance of British troops in Greece, the .establishment of a German warning net in Bulgaria was of vital importance. The Bulgarian Government agreed to admit to its territory one Luftwaffe signal company consisting of 200 men, dressed in civilian clothes, who were to operate an aircraft reporting and warning service. The Luftwaffe, however, first asked permission to dispatch two companies, then a few days later increased this figure to three companies, because incoming reports indicated that the British were constructing air bases on the Greek mainland and the Aegean islands and were bringing in a steadily increasing number of long-range bombardment planes. The German negotiations with the Bulgarian military authorities made little progress because of the adverse effect of the reverses suffered by the Italians in Albania. By the end of 1940, however, an agreement was reached, and by mid-January all three Luftwaffe signal companies, their personnel disguised in civilian clothes, were operating on the mountain range which extends across Bulgaria.

During the political and military negotiations between German and Bulgarian leaders, the latter were very hesitant. Their attitude was motivated by fear of Turkish intervention in the event of a German attack on Greece and their concern over Soviet reaction. After the German military mission had established itself in Romania, the Soviet Union offered to send a military mission to Bulgaria, This offer, made In late November, was rejected, and the Bulgarian Government feared that, as soon as the German military intervention in Bulgaria became manifest, the Soviet Union .night seek to recoup itself through the occupation of the Bulgarian Black Sea port of Varna. The Bulgarians therefore insisted that .ill preparatory measures that the Germans intended to take in Bulgaria be carried out in the utmost secrecy and requested that Germany supply Bulgaria with arms and equipment to reinforce the Black Sea coast defenses. This would include the delivery of modern coast artillery and antiaircraft batteries with the necessary ammunition, as well as furnishing mines and mine-laying vessels. Moreover, German naval experts were to assist in the construction of new coastal defenses.

Hitler promised early compliance with these requests in order to obtain in return some concessions from the Bulgarian Government. One concession was the permission to send a joint military mission, composed of officers from all three services who v/ere to travel through Bulgaria disguised as civilians. Upon returning to Germany, the chief of the mission reported that, in view of the inadequate billeting facilities, the poor condition of roads and bridges, the limited supply of rations, fodder, combustibles, and motor fuel, as well as the absence of reliable maps, operations launched in the Balkans during the wet and cold seasons presented problems that were difficult, though not insurmountable. If appropriate measures, such as improving the roads, reinforcing the bridges, equipping the troops with light motor vehicles and snowplows, employing more German transportation experts, and preparing better maps, were introduced, the attack could be launched even in winter. Since it was generally assumed that major military operations in the Balkans were not practicable. In winter it would be all the easier to camouflage Operation MARITA, inasmuch as nobody would believe that the Germans were feverishly planning and preparing an operation for that time of the year. As an initial step, Bulgaria should permit the entry of a mission of technical experts, whose presence would be kept secret. The mission was to supervise the improvement of the road net and bridges by indigenous labor forces and got acquainted with local conditions, especially those pertaining to the weather.

On 9 January Hitler approved these suggestions and agreed that the first Gorman elements should cross the Danube as soon as the ice on the river could carry them. It was expected that the crossings could be effected between 10 and 15 February. By that time the Luftwaffe was to have assembled sufficient forces to provide adequate air cover. The concentration of fore 3 for Operation MARITA wa-s to be accomplished by 26 March. At that time the Italians were to pin down the maximum number of Greek forces in Albania so that only a relatively few Greek divisions would block the German thrust toward Salonika. Bulgaria was to be approached about billeting facilities for the first Gorman elements to arrive south of the Danube.

After issuing these instructions, Hitler evaluated the overall situation in the Balkans. In his opinion Romania was the only friendly and Bulgaria the only loyal country on which the Axis Powers could rely. King Boris's hesitations in joining the Tripartite Pact were regarded as motivated only by fear of the Soviet Union, whose apparent aim it was to use Bulgaria as an assembly area for an operation leading to the seizure of the Bosporus. The greater the pressure applied by the Russians, the more likely was Bulgaria's adherence to the Tripartite Pact, Yugoslavia maintained a reserved attitude toward the Axis powers; the leaders of that country wanted to be on the winning side without having to take any active part and were therefore playing for time.

At the beginning of January Hitler issued instructions that the Soviet Union should not be informed of German intentions in the Balkans until it made official inquiries. A few days later he changed his mind. Since rumors of an imminent German entry into Bulgaria were circulating at the time — these rumors prompted the Greek minister in Berlin to make inquiries at the Foreign Ministry and induced the Bulgarian Government to issue an official denial — Hitler deemed it advisable to forestall a Soviet demarshe. Consequently, about 10 January the Russian ambassador in Berlin was informed of the transfer of German troops to Romania. The Soviet Union showed its concern about this information by filing a protest note in Berlin, whereupon Hitler ordered that all discernible preparations for the Danube crossing into Bulgaria be discontinued until further notice. Although he apparently did not feel that the execution of Operation MARITA would lead to a war with Russia, he seemed to believe that the Soviet Union might attempt to incite Turkey to take up arms against Germany.

During the conferences between Hitler and Mussolini, which took place from 18 to 20 January, the Italians were fully informed about the imminent march into Bulgaria and the intended attack on Greece. On 20 January, during a review of the overall political and military situation, Hitler stated that three objectives were to be stained by the strategic concentration of German forces in Romania. First, an attack was to be launched against Greece. So as to prevent the British from gaining a foothold in that country. Second, Bulgaria was to be protected against an attack by the Soviet Union and Turkey. Third, the inviolability of Romanian territory was to be guaranteed by the presence of Gorman forces. Each of these objectives required the formation of specific contingents of troops, and it was therefore necessary to employ very strong forces, whose assembly would take considerable time. Since it was highly desirable to effect this assembly without enemy interference, the German plans must not be revealed prematurely. For this reason the crossing of the Danube must be delayed as long as possible and, once it was executed, the attack on Greece must bo launched at the earliest moment. In all probability, Turkey would remain neutral, which would be most desirable since the consequences of Turkey joining Great Britain and placing its airfields at the latter's disposal could be quite unpleasant. Romania's internal situation was not fully clarified, but Hitler felt confidence that General Antonescu would be capable of keeping it in hand. During a conference between Gen. Alfredo Guzzoni, the Italian Assistant Secretary of War, and Field Marshal Keitel, which took place on 19 January, the latter gained the impression that, in view of the situation in Libya and Albania, the Italians would be unable to support the German attack on Greece. On the other hand, Guzzoni asked the Germans to abstain from sending troops to Albania as planned for Operation ALPENVEILCHEN. This German plan called for the transfer of ore mountain corps composed of three divisions, to Albania. Flanked by Italian troops, these forces were to break through the Greek front at a suitable point. The plan was finally-abandoned, and the Germans were thus able to concentrate their efforts on assembling forces for Operation MARITA.

In view of the prevailing uncertainty of Turkey's stand, the Bulgarian Government preferred not to join the Tripartite Pact before the entry of German troops on its territory. Moreover, this step was to be contingent upon the prior arrival of sufficient German antiaircraft units on Bulgarian soil.

On 28 January Hitler decided that the entry of German troops into Bulgaria was to depend upon the completion of the secret assembly of the VIII Air Corps in Romania, the establishment of adequate antiaircraft protection and coastal defenses at the ports of Varna, Constantsa, and Burgas, and the provision of air cover over the Danube crossing points. The assembly of German forces in Romania was to continue without letup. The new target date for Operation MARITA — on or about 1 April — must be adhered to by the services. Antiaircraft units were not to move into Bulgaria before the other German troops. Bulgaria was not to proceed with a general mobilization before sufficient numbers of German troops had arrived in that country. The Bulgarian Air Force and antiaircraft units, as well as the civil defense organization, were to be unobtrusively alerted. German military forces were to occupy Tulcea to secure the region around the Danube estuary against seizure by the Russians.

A memorandum from the Armed Forces Operations Staff to the Foreign Ministry called special attention to the fact that no announcement of Bulgaria's adherence to the Tripartite Pact was to be made until immediately before German troops entered that country. From a military point of view it would be desirable if non-aggression pacts between Bulgaria and Turkey, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, and Germany and Yugoslavia could be concluded before this event. The logistical problems of Operation MARITA would be greatly eased if, after the entry of German forces into Bulgaria, it would be possible to route supplies via Yugoslavia.

Upon request of the Army High Command, Hitler gave his permission to resume preparations for bridge construction on both sides of the Danube. The actual construction, however, was to be delayed as long as possible. The German forces stationed in southern Romania v:ere to be ready to cross into Bulgaria when these preparations could no longer be kept secret. The Twelfth Army was to march from Romania into Bulgaria, move into the assembly areas along the Greek border, and simultaneously provide flank cover against a possible attack by Turkey. The Twelfth Army forces were to be divided into three echelons. The first, under the command of First Panzer Group (a headquarters in charge of an armored force of army size, but operating in conjunction with an army), was to be detrained in Romania' by 10 February. It was to consist of three corps headquarters, and three panzer, three infantry, and one and one-half motorized infantry divisions. The second echelon was to be composed of a corps headquarters and one panzer, one infantry, and two mountain divisions, as well as one independent infantry regiment. The third echelon was to consist of one corps headquarters and six infantry divisions. The last two echelons were to detrain in Romania between 10 February and 27 March 1941.

Chapter 3.

The Other Balkan Countries

I. Turkey

If Bulgaria repeatedly postponed joining the Tripartite Pact, it was primarily because of its concern over Turkish intervention. Actually, negotiations for a Bulgarian-Turkish treaty of friendship were being carried on throughout January 1941. These were progressing satisfactorily, and the terms of the treaty proposed by the Turkish Government indicated clearly the latter's desire to keep out of the war. The signing of the treaty was announced on 17 February. Both countries stated that the immutable basis of their foreign policy was to refrain from attacking one another.

In German eyes this was by no means a guarantee that Turkey would stand aloof while German troops first entered Bulgaria and then attacked Greece, Turkey's ally. In the meantime Hitler had given his approval for bridging the Danube on 20 February; he subsequently acceded to a Bulgarian request for an eight-day postponement and set the final date as 28 February. The entry of German troops into Bulgaria was scheduled for 2 March, the day after the Bulgarian Government was to sign the Tripartite Pact. On the day the bridge construction operation was to start, the German ambassador in Ankara was to inform the Turkish Government of the impending entry of German troops into Bulgaria and of Bulgaria's decision to join the Axis Powers. Moreover, he was to announce Hitler's intention of sending a personal message to Turkey's president.

On the basis of information received from Ankara, Hitler arrived at the conclusion that the danger of Turkey's intervention had been averted. His confidence remained unshaken despite reports concerning the meetings that had taken place in Ankara on 28 February between President Ismet Inoenue and British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. These meetings stressed mutual respect for and adherence to the Turkish-British alliance, but apparently the British had been unsuccessful in inducing the Turks to intervene in the Balkans.

The bridge construction across the Danube began at 0700 on 28 February. At the same time, the first Gorman unit, an antiaircraft battalion which had been assembled in southern Romania, crossed the Bulgarian border en route to Varna, where it arrived the same evening. The 5th and 11th Panzer Divisions, stationed in the Cernavoda area, were alerted to move up to the Bulgarian-Turkish border even before the general entry of German troops into Bulgaria had been effected. This turned out to be an unnecessary precaution. On 1 March Bulgaria officially joined the Tripartite Pact during a ceremony held in Vienna. On this occasion the Bulgarian premier emphasized that Bulgaria would faithfully adhere to the treaties of friendship it had previously concluded with its neighbors — in addition to the treaty just concluded with Turkey. Bulgaria had signed a treaty of friendship with Yugoslavia in 1937 and a non-aggression pact with Greece in 1938 — and was determined to maintain and further develop its traditionally friendly relations with the Soviet Union."

After the construction of the Danube bridges had been completed according to plan, road repair and maintenance crews were sent ahead of the German troops, which made their official entry into Bulgaria at 0600 on 2 March. The VIII Air Corps moved in simultaneously, and most of its formations arrived at the. airfields near Sofiya and Plovdiv by 4. March. As soon as the bridging operation had started, all outgoing telegraph and telephone communications were stopped by German counterintelligence agents in Bulgaria, and on 2 March the Bulgarian Government closed its borders with Turkey, Greece, and Yugoslavia. The international reaction to the German entry into Bulgaria was unexpectedly mild. Oreat Britain broke off diplomatic relations with Bulgaria. Yugoslavia, now completely isolated, appeared more amenable to German suggestions to join the Tripartite Pact. The German minister in Athens discontinued his conversations with Greek officials; hovever, in conformity with Hitler's instructions diplomatic relations with Greece were not broken off. This enabled the Germans to receive reliable information from that country until shortly before they started their attack. According to reports received from Athens, motorized British and Imperial troops began to disembark at Piraeus and Volos during the first days of March.

Immediately after the German entry into Bulgaria, Turkey closed the Dardanelles and maintained a reserved attitude. On 4 March US president received Hitler's message explaining that the entry of German troops into Bulgaria was the only possible solution to the predicament that confronted Germany when the British began to infiltrate Greece. Pointing to the German-Turkish alliance during World War I, Hitler emphasized his peaceful intentions toward Turkey and guaranteed that German troops would stay at least thirty-five; miles from the Turkish border. In the reply, which was handed to the Fuehrer by the Turkish ambassador in Berlin in mid-March, President Inoenue also made reference to the former alliance and expressed the hope that the friendly relations existing between their two countries would be maintained in the future. After receiving this reply to his note, Hitler was no longer apprehensive of Turkey's attitude. However, in order to go one step farther and put Turkey under an obligation, Hitler contemplated giving Turkey that strip of Greek territory around Adrianople through which the Orient Express passes on its way to Istanbul.

The occupation of Bulgaria proceeded according to schedule. By 9 March the advance detachments of the leading infantry divisions had arrived at the Greek-Bulgarian border, and the 5th and 11th Panzer Divisions were fully assembled in their designated areas within fifty miles of the Turkish-Bulgarian border, Eight days later the first and second echelons, consisting of four corps, eleven and one-half divisions, and one infantry regiment, arrived on Bulgarian territory. In accordance with previous agreements, Sofiya, which the Bulgarians intended to declare an open city, v/as net occupied by combat troops but only by service elements. The Twelfth Army under Field Marshal Wilhelm List established its headquarters south of Sofiya and initiated the transfer of the German divisions to their assembly east along the Greek-Bulgarian border.

During that time the third echelon was stiil retraining in Romania. As early as 7 March the Army High Command had pointed out that, in view of Turkey's more and more favorable attitude toward the German occupation of Bulgaria, it would be advisable to keep the six infantry divisions of this echelon in Romania to make sure that they would be promptly available for Operation BARBAROSSA and would not be exhausted by long marches.

II. Yugoslavia

Throughout this period Yugoslavia had successfully avoided being drawn into the Italian-Greek conflict. Hitler's policy was to induce the Yugoslav political leaders to collaborate with Germany and Italy. On 28 November 1940, during a conference with Yugoslavia's Foreign Minister Lazar Cincar-Marcovic, the Fuehrer offered to sign a non-aggression pact with Yugoslavia and recommended its adherence to the Tripartite Pact, Hitler mentioned on that occasion that he intended to intervene in the Balkans by assisting the Italians against Greece. Once the British forces had been driven out of the Balkans, frontier corrections would have to be made, and Yugoslavia might be given an outlet to the Aegean Sea through Salonika. Although Cincar-Marcovic seemed impressed by these arguments, no further progress was made.

During the planning for Operation MARITA, German military leaders pointed repeatedly to Yugoslavia's crucial position and asked that diplomatic pressure be used to induce that country to join the Axis Powers. The use of the Belgrade - Nis - Salonika rail line was essential to the solution of the many logistical problems presented by a campaign in the Balkans.

On 14 February 1941 Hitler and Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop met with the Yugoslav Premier Dragisha Cvetkovic and Cincar-Marcovic. For the Germans the results were as inconclusive as those of the preceding meeting, since the conference did not

lead to the conclusion of any agreements. D Day for Operation MARITA was drawing closer and Yugoslavia still refused to commit

itself Hitler therefore invited Prince Regent Paul to continue

the negotiations, and a meeting took place on 4 March. The prince regent's reaction to the German desiderata was much more favorable than that of the political leaders whom Hitler had met before. However, in strict pursuance of Yugoslavia's policy of neutrality, Prince Paul declined to give the Axis Powers any military support, intimating that this would be incompatible with Yugoslav public opinion. Hitler assured him that he fully appreciated the regent's difficulties and guaranteed him that, oven after adhering to the Tripartite Pact, Yugoslavia would not be required to permit the transit of German troops across its territory. Because of the lack of direct rail lines between Bulgaria and Greece, the use of the Yugoslav railroads leading to Salonika would have been of the utmost importance for the rapid execution of Operation Mi-RITA and the speedy redeployment of forces for Operation BARBAR0SSA. Although the military continued to insist on using the Yugoslav rail net, Hitler attached so much political weight to Yugoslavia's adherence to the Tripartite Pact that he would not let that point interfere with the successful conclusion of the pending negotiations. Moreover, he hoped that later on the Yugoslav Government could be induced to reverse its decision and permit the transit of German supply and materiel shipments across its territory.

For the time being, however, the negotiations with Yugoslavia made little progress, in spite of Hitler's willingness to make concessions. Yugoslav opposition to Italy's interference in the Balkans seemed to be the chief obstacle. By mid-March the situation had reached the point where Mussolini decided to order the reinforcement of the garrisons along the Italian-Yugoslav border. On 18 March the situation suddenly took a turn for the better — the Yugoslav privy council decided to join the Tripartite Pact. The ceremony took place in Vienna on 25 March, when Cvetkovic and Cincar-Marcovic signed the protocol. On this occasion the Axis Powers handed two notes to the Yugoslav representatives. In those they guaranteed to respect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Yugoslavia at all tires and promised that, for the duration of the war, Yugoslavia would not be requested to permit the transit of Axis troops across its territory.

Hitler's triumph over this diplomatic success was, however, short-lived. During the night of 26 - 27 March a military coup d'etat at Belgrade led to the resignation of the existing government and the formation of a new one headed by Gen. Richard D. Simovic, the former commander of the Yugoslav Air Force. Simultaneously, the seventeen-year-old King Peter II acceded to the throne and Prince Regent Paul and his family departed for Greece. The frontiers of Yugoslavia were hermetically sealed. In Belgrade and several other Serbian cities anti-German demonstrations were held and, on 29 March, the Yugoslav Army was mobilized.

Although a nationalistic wave, of enthusiasm swept the entire country with the exception of Croatia, the realities of the military situation gave little reason for optimism. The entire country was surrounded by Axis forces except for the narrow strip of common border with Greece. The situation of the Yugoslav Army was rendered particularly difficult by the shortage of modern weapons. Moreover, since most of its equipment had been produced in Germany or in armament plants under German control, it was impossible to renew the supply of ammunition.

On 27 March the new Yugoslav foreign minister immediately assured the German minister in Belgrade that his country wanted to maintain its friendly relations with Germany. Although it would not ratify its adherence to the Tripartite Pact, Yugoslavia did not want to cancel any standing agreements. Despite this information Hitler was convinced that the new government was anti-German and opposed to the pact and that Yugoslavia would sooner or later join the Western Powers. He therefore called a meeting of the commanders in chief of the .army and Luftwaffe and their chiefs of staff, Ribbentrop, Keitel, and Generaloberst (General) Alfred Jodl for 1300 on 27 March, He informed them that he had decided to "destroy Yugoslavia as a military power and sovereign state." This would have to be accomplished with a minimum of delay and with the assistance of those nations that had borders in common with Yugoslavia. Italy, Hungary, and to a certain ox-tent Bulgaria, would have to lend direct military support, whereas Romania's principal role was to block any attempts at Soviet intervention. The annihilation of the Yugoslav state would have to be executed in blitzkrieg manner. The three services would be responsible for making the necessary preparations with utmost speed.

Following these explanations Hitler issued the over-all instructions for the execution of the operation against Yugoslavia and asked the commanders in chief of the Army and Luftwaffe to submit their plans without delay. These instructions were laid down in Directive No. 25, which was signed by Hitler the same evening and immediately issued to the services.

In a telegram sent to Mussolini on 27 March, Hitler informed the Italian chief of state that he had made all preparations "to meet a critical development by taking the necessary military countermeasures," and that he had acquainted the Hungarian and Bulgarian ministers with his views en the situation in an attempt to rouse the interest of their respective governments to lending military support. Moreover, he asked the Duce "not to start any new ventures in Albania during the next few days" but "to cover the most important passes leading from Yugoslavia to Albania with all available forces and to quickly reinforce the Italian troops along the Italian-Yugoslav border."

A written confirmation of this telegram was handed to Mussolini the next day and negotiations regarding Italy's participation in a war against Yugoslavia were initiated immediately. The Germans submitted a memorandum containing suggestions to promote the co-ordination of the German and Italian operations against Yugoslavia, The memorandum outlined the German plans and assigned the following missions to the Italian forces:

a. To protect the flank of the German attack forces, which were to be assembled around Graz, by moving all immediately available ground forces in the direction of Split and Jajce;

b. To switch to the defensive along the Greek-Albanian front and assemble an attack force, which was to link up with the Germans driving toward Skoplje and points farther south;

c. To neutralize the Yugoslav naval forces in the Adriatic;

d. To resume the offensive on the Greek front in Albania at a later date,

Mussolini approved the German plans and instructed General Guzzoni to comply with them. As a result, the Italian army group in Albania diverted four divisions to the protection of the eastern and northern borders of that country where they faced Yugoslavia.

No definite agreement had been made about possible co-operation between the German and Italian naval forces in the war against Greece. At the beginning of March, during a conversation between General Guzzoni and the German liaison officer with the Italian armed forces, the former had emphasized the necessity of defining the German and Italian military objectives in the Balkans and of assigning liaison staffs to the field commands. However, Hitler was not interested in any such agreement because of continued Italian reverses in Albania. Finally, he decided that liaison officers might bo exchanged between Twelfth Army and the Italian commander in Albania. The Italians were not supposed to know any details of Operation MARITA or its target date until six days before D Day.

When first approached, the Hungarians showed little enthusiasm for participating in the campaign against Yugoslavia. They made no immediate military preparations, but gave their permission for the assembly of one German corps near the western Hungarian border southwest of lake Balaton.

Romanian units were to guard the Romanian-Yugoslav border and, together with the Gorman military mission stationed in that country, provide rear guard protection against an attack on the Soviet Union. Antor.escu was greatly concerned over the possibility of Russian intervention in the Balkans as soon as Germany invaded Yugoslavia. His apprehensions were based on rumors regarding the signature of a treaty of non-aggression and friendship between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. Hitler tried to reassure him by-promising maximum German support and ordering the immediate reinforcement of the German antiaircraft artillery units in Romania and the transfer of additional fire-fighting forces to the oil region.

King Boris of Bulgaria refused to lend active support in the campaigns against Greece and Yugoslavia. He pointed out that by 15 April only five Bulgarian divisions would be available for deployment along the Turkish border and that he could not possibly commit any forces elsewhere.

On 3 April a Yugoslav delegation arrived in Moscow to sign a pact of mutual assistance with the Soviet Union. Instead, they signed a treaty of friendship and non-aggression two days later. By concluding this treaty the Soviet Government apparently wanted to show its interest in Yugoslavia and the Balkans without much hope that this gesture would induce Hitler to reconsider his decision to attack Yugoslavia. The next day, 6 April 1941, the Luftwaffe unleashed an air attack on Belgrade and the German Army started to invade Yugoslavia.

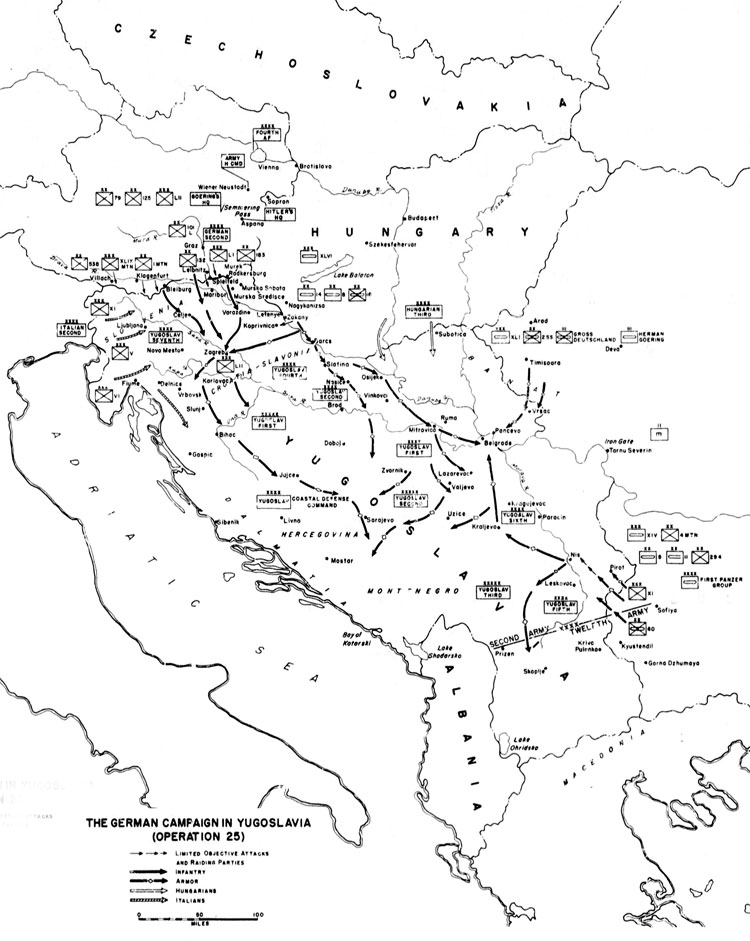

PART TWO. THE YUGOSLAV CAMPAIGN (Operation 25)

Upon his assumption of power on 27 March 1941, General Simovic, the new head of the Yugoslav Government, was faced with a difficult situation. Realizing that Germany was making feverish preparations to invade Yugoslavia, he tried his utmost to unify his government by including representative Croat elements. It was not until 3 April — just three days before the German attack was launched — that the Croat leaders finally joined the Simovic government. Upon entering the cabinet, Croat representatives appealed to their people to give the new regime whole-hearted support. However, any semblance of national solidarity was to be short lived. When Croatia proclaimed itself an independent state with Hitler's blessings on 10 April, the Croat political leaders promptly left the national government in Belgrade and returned to Zagreb. Thus the cleft in Yugoslavia's national unity, superficially closed for exactly seven days, became final and complete.

While the Simovic government made every effort to maintain friendly relations with Germany, Hitler was bent on settling the issue by force of arms. Preparations for the rapid conquest of Yugoslavia were hastened so as not to jeopardize the impending campaign against Russia. Germany's limited resources precluded the possibility of tying down forces in Yugoslavia for a;v protracted period while simultaneously invading the Soviet Union.

Whereas the German General Staff had prepared studies for the invasion of almost every European country, the possibility of an attack on Yugoslavia had hitherto not been considered try by Army planners. For a better understanding of the problems involved in the campaign against Yugoslavia, it is necessary to examine the topographic features of that country.

Chapter 4. Military Topography

Geographically the Balkans extend from the Danube to the Aegean and from the Black Sea to the Adriatic. (Map 1) Mountain ranges and narrow, mountain-lined valleys are characteristic of the Balkan peninsula, of which Yugoslavia constitutes the northwestern and central portion. Central Yugoslavia is a plateau that slopes gently toward the Danube Valley and gradually merges into the Hungarian plains.

The Yugoslav coastline along the Adriatic extends for approximately 400 miles and is fronted by numerous small islands. The Dalmatian Alps, which run along the coast, constitute a formidable barrier since good roads are scarce. Stretching across the peninsula, roughly from east to vest, are the Balkan Mountains. The ranges are high, rough, and rugged, and are interstected by numerous passes which, however, can be successfully negotiated by specially trained and equipped mountain troops.

The inland frontiers of Yugoslavia extend some 1,500 miles and border on Italy, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, and Albania, Covering a land surface approximately the size of the State of Oregon, Y,^oslavia has a population of almost 16 million, of which 5 million Serbs and 3 million Croats constitute thn two loading ethnic groups. In the northern part of the country a German minority element numbers about half a million. The largest cities are Belgrade, the national capital, with 400,000 inhabitants, and Zagreb, the principal Croat city, with 200,000.

The country can be roughly divided into five distinct natural geographic regions. The so-called Pannonian Basin, within which the national capital of Belgrade is centrally located, is by far thy most important industrial portion. The Sava and Drava valleys link this area with the Slovene Alps, the forerunners of the more formidable Julian Alps. The Morava - Vardar depression extends southward from Belgrade to the jreek frontier. The Adriatic coastal belt extends from Italy in the north to Albania in the south. The Dalmatian Alps rise directly out of the sea and overshadow the central mountain or Dinaric Karst region farther inland.

There are several great routes of communication in the Balkans. One of these follows the Morava and Vardar Rivers from Budapest to Salonika and connects the Danube with the Aegean. The beat roads and railroad lines are to be found in the northern and northeastern fringes of Yugoslavia.

Because of its difficult terrain, Yugoslavia is far from being ideally suited for the conduct of major military operations. This poorly developed, rugged, and mountainous country, with its limited routes of communication and sparsely populated srea, is bound to raise havoc with an invader's communications, movements, and logistical support.

Almost all of the rivers, including the Drava, Sava, and Morava, are tributaries of the Danube, which flows through the northwestern part of Yugoslavia for about 350 miles. Soon after crossing the northern border an attacking ground force is confronted by three formidable river barriers: — the Mura, the Drava, and the Sava. At the time of the spring thaw these rivers resemble swollen torrents; the Drava at Bares and the lower course of the Sava become as wide as the Mississippi at St. Louis. It is therefore of vital importance for the invader to seize the key bridges across these rivers while they are still intact.

Chapter 5. Hitler's Concept of the Strategic Factors

During the conference that took place in the afternoon of 27 March 1941, Hitler formulated overall strategic plans for the projected military operation against Yugoslavia. The decisions reached at this meeting were summarized in Directive No. 25, which was disseminated to the three armnd services on the same day. The campaign against Yugoslavia took its cover name — Operation 25 —- from this directive.

Hitler declared that the uprising in Yugoslavia had drastically changed the entire political situation in the Balkans. He maintained that Yugoslavia must now be regarded as an enemy and must be destroyed as quickly as possible despite any assurances that might be forthcoming from the new Yugoslav Government. Hungary and Bulgaria were to be induced to participate in the operations by extending to their, the opportunity of regaining Banat and Macedonia, respectively. By the same token, political promises were to be extended to the Croats premises that were bound to have all the more telling effect since they would render even more acute the internal dissension within Yugoslavia.

In view of Yugoslavia's difficult terrain, the German plans called for a two-pronged drive in the general direction of Belgrade, with one assault force coming from southeastern Austria and the other from western Eulgaria. These forces were to crush the Yugoslav armed forces in the north. Cimultaneously, the southernmost part of Yugoslavia was to be used as a jump-off area for a combined German-Italian offensive against Greece. Vital as the early capture of Belgrade proper was considered to be, possession of the Belgrade - Mis - Salonika rail line and highway and of the Danube waterway was of even greater strategic importance to the German supply system. Hitler therefore arrived at the following conclusions:

1. As soon as sufficient forces became available and the weather conditions permitted, the Luftwaffe was to destroy the city of Belgrade as well as the ground installations of the Yugoslav Air Force, by means of uninterrupted day-and-night bombing attacks. The launching of Operation MARITA was to coincide with the initial air bombardment.

2. All forces already available in Bulgaria and Romania could be utilized for the ground attacks, one to be launched toward Belgrade from the Sofiya region, the other toward Skoplje from the Kyustendil - Gorna Dzhumaya area. However, approximately one division and sufficient antiaircraft elements must remain in place to protect the vital Romanian oil fields. The guarding of the Turkish frontier was to be left to the Bulgarians for the time being, but, if practicable, one armored division v/as to be kept in readiness behind the Bulgarian frontier security forces.

3. The attack from Austria toward the southeast was to be launched as soon as the necessary forces could be as sembled in the Oaz area. The ultimate decision as to whether Hungarian soil should be used for staging the drive against Yugoslavia was to be lsft to the Army. Security forces along the northern Yugoslav frontier were to be reinforced at once. Even before the main attacks could be launched, vital points should be seized and made secure along the northern and eastern Yugoslav border. Any such limited—objective attacks were to be so timed as to coincide witn the air bombardment of Belgrade.

4. The Luftwaffe was to lend tactical support and

cover the ground operations in the vicinity of the Yugoslav border end co-ordinate its efforts with the requirements of the Army. Adequate antiaircraft protection was

to be provided in the vital concentration areas around

Graz, Klagenfurt, Villach, Looben, and Vienna.

Chapter 6.

The Plan of Attack

I. The Outline Plan

Working under tremendous pressure, the Army High Command developed the combined, outline plan for the Yugoslav and Greek campaigns within twenty-four hours of the military revolt in Yugoslavia. After this plan had been submitted to and approved by Hitler, it was incorporated into Directive No. 25.

This outline plan envisaged the following offensive operations:

1. One attack force was to drive southward from the former Austrian province of Styria and from southwestern Hungary. This force was to destroy the enemy armies in Croatia and drive southeastward between the Sava and Drava Rivers toward Belgrade. The mechanized divisions of this assault group were to co-ordinate their advance with the other attack forces that were to close in on the Yugoslav capital from other directions so thai, the bulk of the enemy forces would bo unalle to make an orderly withdrawal into the mountains.

2. The second force was to advance toward Belgrade

from the Sofiya area in western Bulgaria, take the capital,

and secure the Danube so that river traffic could be

reopened at an early date.

3. A third attack force was to thrust from south of Sofiya and drive in the general direction of Skoplje in an effort to cut off the Yugoslav Army from the Greek and British forces, while ai the same time easing the precarious situation of the Italians in Albania.

4. Finally, elements of tha German Twelfth Army, which were poised and ready to invade Greece from Bulgarian bases and had the difficult task of surmounting the hazardous terrain fortified by the Metaxas Line, were to pass through the southern tip of Yugoslavia, execute an enveloping thrust via the Vardar Valley toward Salonika, and thus ease the task of the German forces that were conducting the frontal assault against the Greek fortified positions.

II. The Timing of the Attacks

In its original version, the outline plan for Operation 25 called for the air bombardment of Belgrade and the ground installations of the Yugoslav Air Force to take place on 1 April, the invasion of Greece — Operation MARITA — on 2 or 3 April, and ground attacks against Yugoslavia between 8 and 15 April.

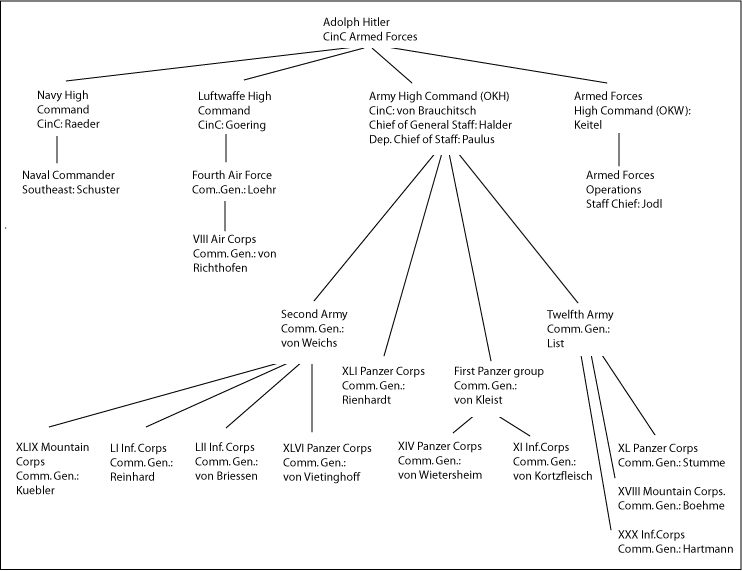

During the afternoon of 29 March the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Army, Generalleutnant (major General) Friedrich Paulus presided over a special conference in Vienna at which the plans of attack and timetable for the operations against Greeco and Yugoslavia were discussed. Present with their respective cniefs of staff were Field Marshal List, the commander of Twelfth Army, Generaloberst (General) Maximilian von Weichs of Second Army, and Generaloberst (General) Ewald von Kleist of the First Panzer Group. Field Marshal List was brought up to date on the changes in the situation necessitated by the Yugoslav campaign, and all commanders were fully briefed on the projected plans for the conduct of the operations. Decisions were reached as to which units were to participate in the various thrusts from Austria and Hungary under the command of Second Army. In addition, the corps headquarters and GHQ units were selected and assigned.

One of the subject: discussed during this meeting was the participation of Germany's allies and satellites in the Yugoslav campaign. Since the Italians in Albania had demonstrated their inability to mount any offensive operations and the Italian Second Army deployed in northern Italy apparently would not be ready for action until 22 April, any real assistance from that side was not to be expected. At any rate, according to thu German urmy Command plans, the Yugoslav operations would be almost completed by the time the Italians would be ready. The Hungarians ucceded to all German requests for the use of their territory and agreed to take an active part in the operations by committing contingents, which were to be subordinated to the German Army High Command. At the conclusion of the conference, General Paulus proceeded to Budapest to discuss details of the operation with the Hungarian general staff.

Another result of the conference of 29 March was the decision to delay the initial air attacks so that they would coincide more closely with the attack on Greece. The purpose of this measure was to bring Operation MARITA into a closer relationship with Operation 25. The revised timetable thus foresaw that the attacks of Twelfth Army to the south and west and the air bombardment would be launched simultaneously on 6 April, the thrust of First Panzer Group on 8 April, and the Second Army attack on 12 April. These deadlines were adhered to with the exception of D Lay for Second Army, which was moved up when the rapid successes scored by the probing attacks led to the decision of getting off to a "flying start."

III. Second Army

In the final version of the plan of attack tho Second Army was to jump off on 10 April with its mechanized forces driving in the general direction of Belgrade between the Drava and Sava Rivers. The terrain between the two rivers was considered ideal for armored warfare, and no serious obstacles were reported. The army was greatly concerned, however, over the prospect of finding key bridges demolished, especially since little bridging equipment was available and the rivers were swollen by spring thaws. For this reason the lead elements of the XLVI Panzer Corps were to conduct limited objective attacks as early as 6 April in order to seize end secure the highway and railroad bridges across tho Drava near Bares, In this manner the corps would be able to get off on its thrust toward Belgrade by 8 April, the same time that the First Panzer Group was to attack from the southeast. One motorized column was to be diverted to the southwest with the mission of capturing Zagreb at the earliest possible moment.

Farther to the west, where the terrain becomes more and more mountainous, the LI Infantry Corps was to jump off on 10 April and drive in the direction of Zagreb with two infantry divisions. Here, too, limited objective attacks vere to be carried out during the preceding days so that strategic points in the proximity of the frontier could be secured.

On the same day, and as soon as sufficient troops became available, the XLIX Mountain Corps was to advance toward Celje.

IV. First Panzer Group