Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

"DROPSHOT" - AMERICAN P:AN FOR WAR WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1957

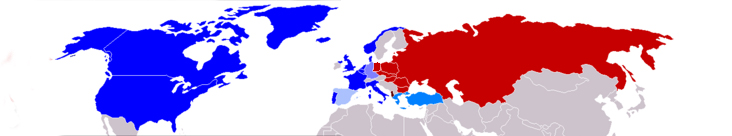

After Nazi's defeat in 1945, Soviet Union emerged as a new superpower with its own aggressive agenda to promote Communism and eventually, dominate in the world. American Joint Chiefs of Stuff had to contemplate probable Soviet's actions and by 1949 came up with a plane of effective military response. "Dropshot" is a result of these contingency planning, a frightening but realistic scenario of the Third World War, started between NATO and USSR in Europe and all over the world on January 1, 1957.

VOLUME 1. THE OUTBREAK OF THE WAR, DISASTER, AND DEFENSE.

1. MISSION

1. To impose the national war objectives of the United States on the USSR and her allies.

2. BASIC ASSUMPTION

2. On or about 1 January 1957, war against the USSR has been forced upon the United States by an act of aggression of the USSR and/or her satellites.

3. NATIONAL WAR OBJECTIVES OF THE UNITED STATES

3. The conclusions of NSC 20/4 approved by the President, state the aims and objectives of the United States with respect to the USSR. November 23, 1948

REPORT BY THE NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL ON US OBJECTIVES WITH RESPECT TO THE USSR TO COUNTER SOVIET THREATS TO U.S. SECURITY

THE POBLEM

1. To assess and appraise existing and foreseeable threats to our national security currently posed by the USSR; and to formulate our objectives and aims as a guide in determining measures required to counter such threats.

ANALYSIS OF THE NATURE OF THREATS

2. The will and ability of the leaders of the USSR to pursue policies which threaten the security of the United States constitute the greatest single danger to the United States within the foreseeable future.

3. Communist ideology and Soviet behavior clearly demonstrate that the ultimate objective of the leaders of the USSR is the domination of the world. Soviet leaders hold that the Soviet Communist party is the militant vanguard of the world proletariat in its rise to political power and that the USSR, base of the world Communist movement, will not be safe until the non-Communist nations have been so reduced in strength and numbers that Communist influence is dominant throughout the world. The immediate goal of top priority since the recent war has been the political conquest of Western Europe. The resistance of the United States is recognized by the USSR as a major obstacle to the attainment of these goals.

4. The Soviet leaders appear to be pursuing these aims by:

a. Endeavoring to insert Soviet-controlled groups into positions of power and influence everywhere, seizing every opportunity presented by weakness and instability in other states, and exploiting to the utmost the techniques of infiltration and propaganda, as well as the coercive power of preponderant Soviet military strength.

b. Waging political, economic, and psychological warfare against all elements resistant to Communist purposes and in particular attempting to prevent or retard the recovery of and cooperation among Western European countries.

c. Building up as rapidly as possible the war potential of the Soviet orbit in anticipation of war, which in Communist thinking is inevitable.

Both the immediate purposes and the ultimate objective of the Soviet leaders are inimical to the security of the United States and will continue to be so indefinitely.

5. The present Soviet ability to threaten U.S. security by measures short of war rests on:

a. The complete and effective centralization of power throughout the USSR and the international Communist movement.

b The persuasive appeal of a pseudoscientific ideology promising panaceas and brought to other peoples by the intensive efforts of a modern totalitarian propaganda machine.

c. The highly effective techniques of subversion, infiltration, and capture of political power, worked out through a half century of study and experiment.

d The power to use the military might of Russia, and of other countries already captured, for purposes of intimidation or, where necessary, military action.

e. The relatively high degree of political and social instability prevailing at this time in other countries, particularly in the European countries affected by the recent war and in the colonial or backward areas on which these European areas are dependent for markets and raw materials.

f. The ability to exploit the margin of tolerance accorded the Communists and their dupes in democratic countries by virtue of the reluctance of such countries to restrict democratic freedoms merely in order to inhibit the activities of a single faction and by the failure of those countries to expose the fallacies and evils of Communism.

6. It is impossible to calculate with any degree of precision the dimensions of the threat to U.S. security presented by these Soviet measures short of war.

The success of these measures depends on a wide variety of currently unpredictable factors, including the degree of resistance encountered elsewhere, the effectiveness of U.S. policy, the development of relationships within the Soviet structure of power, etc. Had the United States not taken vigorous measures during the past two years to stiffen the resistance of Western European and Mediterranean countries to Communist pressures, most of Western Europe would today have been politically captured by the Communist movement. Today, barring some radical alteration of the underlying situation which would give new possibilities to the Communists, the Communists appear to have little chance of effecting at this juncture the political conquest of any countries west of the Lubeck-Trieste line. The unsuccessful outcome of this political offensive has in turn created serious problems for them behind the Iron Curtain, and their policies are today probably motivated in large measure by defensive considerations. However, it cannot be assumed that Soviet capabilities for subversion and political aggression will decrease in the next decade, and they may become even more dangerous than at present.

7. In present circumstances the capabilities of the USSR to threaten U.S. security by the use of armed forces are dangerous and immediate:

a. The USSR, while not capable of sustained and decisive direct military attack against U.S. territory or the Western Hemisphere, is capable of serious submarine warfare and of a limited number of one-way bomber sorties.

b. Present intelligence estimates attribute to Soviet armed forces the capability of overrunning in about six months all of Continental Europe and the Near East as far as Cairo, while simultaneously occupying important continental points in the Far East. Meanwhile, Great Britain could be subjected to severe air and missile bombardment.

c. Russian seizure of these areas would ultimately enhance the Soviet war potential, if sufficient time were allowed and Soviet leaders were able to consolidate Russian control and to integrate Europe into the Soviet system. This would permit an eventual concentration of hostile power which would pose an unacceptable threat to the security of the United States.

8. However, rapid military expansion over Eurasia would tax Soviet logistic facilities and impose a serious strain on [the] Russian economy. If at the same time the USSR were engaged in war with the United States, Soviet capabilities might well, in face of the strategic offensives of the United States, prove unequal to the task of holding the territories seized by the Soviet forces. If the United States were to exploit the potentialities of psychological warfare and subversive activity within the Soviet orbit, the USSR would be faced with increased disaffection, discontent, and underground opposition within the area under Soviet control.

9. Present estimates indicate that the current Soviet capabilities . . . will Progressively increase and that by no later than 1955 the USSR will probably be capable of serious air attacks against the United States with atomic, biological, and chemical weapons, of more extensive submarine operations (including the launching of short-range guided missiles), and of airborne operations to seize advance bases. However, the USSR could not, even then, successfully undertake an invasion of the United States as long as effective U.S. military forces remained in being. Soviet capabilities for overrunning Western Europe and the Near East and for occupying parts of the Far East will probably still exist by 1958.

10. The Soviet capabilities and the increases thereto set forth in this paper would result in a relative increase in Soviet capabilities vis-a-vis the United States and the Western democracies unless offset by factors such as the following:

a. The success of ERP

b. The development of Western Union t and its support by the United States.

c. The increased effectiveness of the military establishments of the United States, Great Britain, and other friendly nations.

d. The development of internal dissension within the USSR and disagreements among the USSR and orbit nations.

11. The USSR has already engaged the United States in a struggle for power. While it cannot be predicted with certainty whether, or when, the present political warfare will involve armed conflict, nevertheless there exists a continuing danger of war at any time.

a. While the possibility of planned Soviet armed actions which would involve this country cannot be ruled out, a careful weighing of the various factors points to the probability that the Soviet government is not now planning any deliberate armed action calculated to involve the United States and is still seeking to achieve its aims primarily by political means, accompanied by military intimidation.

b. War might grow out of incidents between forces in direct contact.

c. War might arise through miscalculation, through failure of either side to estimate accurately how far the other can be pushed. There is the possibility that the USSR will be tempted to take armed action under a miscalculation of the determination and willingness of the United States to resort to force in order to prevent the development of a threat intolerable to U.S. security.

12. In addition to the risk of war, a danger equally to be guarded against is the possibility that Soviet political warfare might seriously weaken the relative position of the United States, enhance Soviet strength, and either lead to our ultimate defeat short of war or force us into war under dangerously unfavorable conditions. Such a result would be facilitated by vacillation, appeasement, or isolationist concepts in our foreign policy, leading to loss of our allies and influence; by internal disunity or subversion; by economic instability in the form of depression or inflation; or by either excessive or inadequate armament and foreign-aid expenditures.

13. To counter threats to our national security and to create conditions conducive to a positive and in the long term mutually beneficial relationship between the Russian people and our own, it is essential that this government formulate general objectives which are capable of sustained pursuit both in time of peace and in the event of war. From the general objectives flow certain specific aims which we seek to accomplish by methods short of war, as well as certain other aims which we seek to accomplish in the event of war.

CONCLUSIONS

Threats to the Security of the United States

14. The gravest threat to the security of the United States within the foreseeable future stems from the hostile designs and formidable power of the USSR and from the nature of the Soviet system.

15. The political, economic, and psychological warfare which the USSR is now waging has dangerous potentialities for weakening the relative world position of the United States and disrupting its traditional institutions by means short of war, unless sufficient resistance is encountered in the policies of this and other non-Communist countries.

16. The risk of war with the USSR is sufficient to warrant, in common prudence, timely and adequate preparation by the United States.

a. Even though present estimates indicate that the Soviet leaders probably do not intend deliberate armed action involving the United States at this time, the possibility of such deliberate resort to war cannot be ruled out.

b. Now and for the foreseeable future there is a continuing danger that war will arise either through Soviet miscalculation of the determination of the United States to use all the means at its command to safeguard its security, through Soviet misinterpretation of our intentions, or through U.S. miscalculation of Soviet reactions to measures which we might take.

17. Soviet domination of the potential power of Eurasia, whether achieved by armed aggression or by political and subversive means, would be strategically and politically unacceptable to the United States.

18. The capability of the United States cither in peace or in the event of war to cope with threats to its security or to gain its objectives would be severely weakened by internal developments, important among which are:

a. Serious espionage, subversion, and sabotage, particularly by concerted and well-directed Communist activity.

b. Prolonged or exaggerated economic instability.

c. Internal political and social disunity.

d. Inadequate or excessive armament or foreign-aid expenditures.

e. An excessive or wasteful usage of our resources in time of peace.

f. Lessening of U.S. prestige and influence through vacillation or appeasement or lack of skill and imagination in the conduct of its foreign policy or by shirking world responsibilities.

g. Development of a false sense of security through a deceptive change in Soviet tactics.

U.S. Objectives and Aims Vis-a-Vis the USSR

19. To counter the threats to our national security and well-being posed by the USSR, our general objectives with respect to Russia, in time of peace as well as in time of war, should be:

a. To reduce the power and influence of the USSR to limits which no longer constitute a threat to the peace, national independence, and stability of the world family of nations.

b. To bring about a basic change in the conduct of international relations by the government in power in Russia, to conform with the purposes and principles set forth in the UN charter.

In pursuing these objectives due care must be taken to avoid permanently impairing our economy and the fundamental values and institutions inherent in our way of life.

20. We should endeavor to achieve our general objectives by methods short of war through the pursuit of the following aims:

a. To encourage and promote the gradual retraction of undue Russian power and influence from the present perimeter areas around traditional Russian boundaries and the emergence of the satellite countries as entities independent of the USSR.

b. To encourage the development among the Russian peoples of attitudes which may help to modify current Soviet behavior and permit a revival of the national life of groups evidencing the ability and determination to achieve and maintain national independence.

c To eradicate the myth by which people remote from Soviet military influence are held in a position of subservience to Moscow and to cause the world at large to see and understand the true nature of the USSR and the Soviet-directed world Communist party and to adopt a logical and realistic attitude toward them, d. To create situations which will compel the Soviet government to recognize the practical undesirability of acting on the basis of its present concepts and the necessity of behaving in accordance with precepts of international conduct, as set forth in the purposes and principles of the UN charter.

21. Attainment of these aims requires that the United States:

a. Develop a level of military readiness which can be maintained as long as necessary as a deterrent to Soviet aggression, as indispensable support to our political attitude toward the USSR, as a source of encouragement to nations resisting Soviet political aggression, and as an adequate basis for immediate military commitments and for rapid mobilization should war prove unavoidable.

b. Assure the internal security of the United States against dangers of sabotage, subversion, and espionage.

c. Maximize our economic potential, including the strengthening of our peace time economy and the establishment of essential reserves readily available in the event of war.

d. Strengthen the orientation toward the United States of the non-Soviet nations and help such of those nations as are able and willing to make an important contribution to U.S. security to increase their economic and political stability and their military capability.

e. Place the maximum strain on the Soviet structure of power and particularly on the relationships between Moscow and the satellite countries.

f. Keep the U.S. public fully informed and cognizant of the threats to our national security so that it will be prepared to support the measures which we must accordingly adopt.

22. In the event of war with the USSR, we should endeavor by successful military and other operations to create conditions which would permit satisfactory accomplishment of U.S. objectives without a predetermined requirement for unconditional surrender. War aims supplemental to our peacetime aims should include:

a. Eliminating Soviet Russian domination in areas outside the borders of any Russian state allowed to exist after the war.

b. Destroying the structure of relationships by which the leaders of the All-Union Communist party have been able to exert moral and disciplinary authority over individual citizens, or groups of citizens, in countries not under Communist control.

c. Assuring that any regime or regimes which may exist on traditional Russian territory in the aftermath of a war:

(1) Do not have sufficient military power to wage aggressive war.

(2) Impose nothing resembling the present Iron Curtain over contacts with the outside world.

d In addition, if any Bolshevik regime is left in any part of the Soviet Union, ensuring that it does not control enough of the military-industrial potential of the Soviet Union to enable it to wage war on comparable terms with any other regime or regimes which may exist on traditional Russian territory.

e. Seeking to create postwar conditions which will:

(1) Prevent the development of power relationships dangerous to the security of the United States and international peace.

(2) Be conducive to the successful development of an effective world organization based upon the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

(3) Permit the earliest practicable discontinuance within the United States of wartime controls.

23. In pursuing the above war aims, we should avoid making irrevocable or premature decisions or commitments respecting border rearrangements, administration of government within enemy territory, independence for national minorities, or postwar responsibility for the readjustment of the inevitable political, economic, and social dislocations resulting from the war. . . .

4. SPECIAL ASSUMPTIONS

4. The North Atlantic Pact nations (the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Italy, Norway, Denmark, Iceland, and Portugal), non-Communist China, the other nations of the British Commonwealth (except India and Pakistan), and the Philippines will be allied. . . .

5. Ireland, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, Greece, Turkey, the Arab League (Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen), Israel, Iran, India, and Pakistan will attempt to remain neutral but will join the Allies if attacked or seriously threatened.

6. Allied with the USSR, either willingly or otherwise, will be Poland, Finland, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Yugoslavia,[' If the present defection of Yugoslavia from the Soviet satellite orbit should continue to 1957. it is not likely that Yugoslavia would ally with the Soviet Union but would attempt to remain neutral and would be committed to resist Soviet and/or satellite attack.] Albania, Romania, Bulgaria, Mongolian People's Republic (Outer Mongolia),

Manchuria, Korea, and Communist China (hereinafter denoted the Soviet powers).

7. Except for Soviet satellites, other countries of the Eastern Hemisphere will attempt to remain neutral, but will submit to adequate armed occupation by either side rather than fight.

8. The Latin American countries will remain neutral or join the Allies. Those that remain noncombatant probably will make their economic resources and possibly their territories available to the Allies.

9. United States programs for European [economic and fiscal] recovery have been completed by 1953 and have been effective to the extent that, by 1957, countries participating therein have achieved political stability and are mutually self-supporting economically.

10. The armed forces of the Western European Allies have been regenerated to the extent that by 1957 they are capable of substantial coordinated defensive military action in Western Europe.

11. Allied forces, of substantially the same military strength and effectiveness as at present, will be available for D-Day deployment in, or will be actually stationed in, Germany, Austria, Trieste, and Japan in 1957, either in the role of occupation forces or by other arrangement.

12. Soviet aggression will be planned in advance and Soviet mobilization TO THE EXTENT REQUIRED BY INITIAL PLANS will be practically completed prior to D-Day. Intelligence of heightened war preparation on the part of the USSR has been received, and Allied mobilization and minimum preparatory force dispositions have been initiated, but time has not permitted significant progress prior to D-Day.

13. The [petrol, oil, lubricants] requirements of the Allies will be such that at least part of the finished products of the Near and Middle East oil-bearing areas will be required by the Allies from the start of a war in 1957.

14. Atomic weapons will be used by both sides. Other weapons of mass destruction (radiological, biological, and chemical warfare) may be used by either side subject to considerations of retaliation and effectiveness.

15. Between now and 1957 the United States will not suffer from either a major depression or a catastrophic inflation.

16. The political and psychological tension as it existed in 1948 between the USSR and the Western or Allied powers will continue relatively unabated until 1957.

17. Russian military and economic potentials have not been appreciably augmented prior to 1957 by acquisition or exploitation of territory not under their control in 1948. . . .

5. OVERALL STRATEGIC CONCEPT

19. In collaboration with our allies, to impose the Allied war objectives upon the USSR by destroying the Soviet will and capacity to resist, by conducting a strategic offensive in Western Eurasia and a strategic defensive in the Far East.

Initially: To defend the Western Hemisphere; to launch an air offensive; to initiate a discriminate containment of the Soviet powers within the general area: North Pole-Greenland Sea-Norwegian Sea-North Sea-Rhine River-Alps-Piave River-Adriatic Sea-Crete-southeastern Turkey-Tigris Valley-Persian Gulf-Himalayas-Southeast Asia-South China Sea-East China Sea-Japan Sea-Tsugaru Strait-Bering Sea-Bering Strait-North Pole; to secure and control essential strategic areas, bases, and lines of communication; and to wage psychological, economic, and underground warfare, while exerting unremitting pressure against the Soviet citadel, utilizing all means to force the maximum attrition of Soviet war resources.

Subsequently: To launch coordinated offensive operations of all arms against the USSR as required.

6. BASIC UNDERTAKINGS

20. In collaboration with our allies:

a. To secure the Western Hemisphere.

b. To conduct an air offensive against the Soviet powers.

c. To hold the United Kingdom.

d. To hold maximum areas in Western Europe.

e. To conduct offensive operations to destroy enemy naval forces, naval bases,

shipping, and supporting facilities.

f. To secure sea and air lines of communication essential to the accomplishment of the overall strategic concept.

g. To secure overseas bases essential to the accomplishment of the overall strategic concept.

h. To expand the overall power of the armed forces for later offensive operations against the Soviet powers, and

i. To provide essential aid to our allies in support of efforts contributing directly to the overall strategic concept.

7. PHASED CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS

21. In the implementation of the overall strategic concept the conduct of the required operations may be considered to fall into four general phases. These phases will not be distinct and will probably overlap as between areas in both time and operation. They are defined as follows:

PHASE I. D-Day to stabilization of initial Soviet offensives, to include the initiation of the Allied [atomic] air offensive.

PHASE II. Stabilization of initial Soviet offensives to Allied initiation of major offensive operations of all arms.

PHASE III. Allied initiation of major offensive operations until Soviet capitulation is obtained.

PHASE IV. Establishment of control and enforcement of surrender terms.

In the event the air offensive, together with other operations, results in Soviet capitulation during Phases I or II, the war would pass immediately into Phase IV. ...

22. Phase I. In collaboration with our allies:

a. Secure the Western Hemisphere.

(1) Maintain surveillance of the approaches to the North American continent.

(2) Provide an area air defense of the most important areas of the United States.

(3) Provide the antiaircraft defense of the most vital installations of the United States.

(4) Provide for the protection of Western Hemisphere coastal and intercoastal shipping and of important ports and harbors in the continental United States.

(5) Ensure the security of the refineries on the islands of Curacao, Aruba,

and Trinidad and of associated sources of oil.

(6) Provide the optimum defense against sabotage, subversion, and espionage.

(7) Establish or secure and defend the following peripheral areas and bases necessary to the defense of the continental United States: Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Labrador, Newfoundland, Bermuda, the Caribbean, northeastern Brazil, and Hawaii.

(8) Defend the sea approaches to the North American continent and to its peripheral bases.

(9) Provide the optimum ground-force defense of the most important areas of the continental United States, including a mobile striking force.

b. Conduct an air offensive against the Soviet powers.

(1) Initiate, as soon as possible after D-Day, strategic air attacks with atomic and conventional bombs against Soviet facilities for the assembly and delivery of weapons of mass destruction; against LOCs [lines of communications], supply bases, and troop concentrations in the USSR, in satellite countries, and in overrun areas, which would blunt Soviet offensives; and against petroleum, electric power, and steel target systems in the USSR, from bases in the United States, Alaska, Okinawa, the United Kingdom, [and] the Cairo-Suez-Aden area and from aircraft carriers when available from primary tasks.

(2) Initiate, as soon as possible after D-Day, air operations against naval targets of the Soviet powers to blunt Soviet sea offensives, with emphasis on the reduction of Soviet submarine capabilities and the offensive mining of enemy waters.

(3) Extend operations as necessary to additional targets both within and outside the USSR essential to the war-making capacity of the Soviet powers.

(4) Maintain policing of target systems reduced in the initial campaigns, c Conduct offensive operations to destroy enemy naval forces, shipping, naval bases, and supporting facilities.

(1) Destroy Soviet naval forces, shipping, naval bases, supporting facilities, and their air defenses.

(2) Mine important enemy ports, and focal sea approaches thereto, in the Baltic-Barents-White Sea area, northeast Asia, the Black Sea, the Adriatic, and the Turkish straits.

(3) Establish a sea blockade of the Soviet powers.

d. Hold the United Kingdom.

(1) Maintain surveillance of the approaches to the United Kingdom.

(2) Provide the air defense of the most critical areas of the United Kingdom.

(3) Provide the antiaircraft [AA] defense of the most critical areas of the United Kingdom.

(4) Provide for the protection of the United Kingdom coastal shipping and of important ports and harbors in the United Kingdom.

(5) Provide the optimum defense against sabotage, subversion, and espionage.

(6) Provide the optimum ground-force defense of the most critical areas of the United Kingdom.

e. Hold the Rhine-Alps-Piave line.

(1) Provide the ground-force defense of the Rhine River line from Switzerland to the Zuider Zee.

(2) Provide the ground-force defense of Italy along the Alps-Piave River line.

(3) Provide tactical air support of Allied ground forces along the Rhine-Alps-Piave line.

(4) Accomplish planned demolitions and interdict Soviet LOCs east of the Rhine-Alps-Piave line.

(5) Provide air defense of areas west of the Rhine-Alps-Piave line.

(6) Provide AA defenses for areas west of the Rhine-Alps-Piave line.

(7) Gain and maintain air superiority over the Rhine-Alps-Piave line.

(8) Provide for the protection of Allied coastal shipping and of important ports and harbors in Western Europe.

f. Hold the area southeastern Turkey-Tigris Valley-Persian Gulf.

(1) Provide the ground, air, and AA defenses of the refineries and associated installations at Bahrein and Ras Tanura and the airfield at Dhahran.

(2) Provide the ground, air, and AA defenses of the Abadan refinery, its associated installations and oil fields, and the key communications and port facilities in that area.

(3) Accomplish planned demolitions and air interdiction of the Soviet LOCs leading through Iran and Turkey.

(4) Gain and maintain air superiority over the Iranian mountain passes and over the southeastern Turkey battle areas.

(5) Provide the ground-force defense of the mountain passes leading into Iraq and the Iranian oil areas.

(6) Provide the ground-force defense of southeastern Turkey.

(7) Provide tactical air support of Allied ground forces.

(8) Provide AA protection for Baghdad, Mosul, the Iskenderun-Aleppo area and the LOCs southward from the latter.

(9) Provide naval local-defense forces in the Bahrein-Dhahran area.

(10) Provide a floating reserve of ground forces.

g. Hold maximum areas of the Middle East and Southeast Asia consistent with indigenous capabilities supported by other Allied courses of action.

(1) Conduct air attacks against Soviet forces which threaten Bandar Abbas and interdict the LOC leading thereto.

(2) Provide ground and air defenses against indigenous Communist forces in Malaya.

(3) Interdict Soviet land and sea LOCs leading into China and neutralize enemy bases in China.

h. Hold Japan, less Hokkaido,

(1) Provide ground and air defenses of Honshu and Kyushu.

(2) Organize, train, and equip Japanese forces prior to D-Day.

(3) Defend the sea approaches to Japan.

(4) Provide naval local-defense forces.

(5) Provide AA defenses for the most important areas.

l. Secure sea and air lines of communication essential to the accomplishment of the overall strategic concept.

(1) Establish a convoy system and control and routing of shipping.

(2) Provide convoy air and surface escorts.

(3) Provide air defense of convoys within effective range of enemy air.

j. Secure overseas bases essential to the accomplishment of the overall strategic concept as follows:

(1) Immediately after D-Day, provide forces by air and sea transport to occupy or recapture Iceland and the Azores and establish necessary air and naval bases thereon.

(a) Immediately after D-Day, or before, if practicable, provide ground, air, and antiaircraft forces to secure and defend Iceland, utilizing airlift as necessary.

(b) As soon as possible after D-Day, provide ground and air units to secure and defend the Azores.

(c) Defend the sea approaches to Iceland and the Azores.

(d) Provide naval local-defense forces for Iceland and the Azores.

(2) Establish or expand and defend Allied bases as required in northwest Africa and North Africa.

(a) Provide air defenses and naval local-defense forces for bases at Port Lyautey and Casablanca.

(b) Provide ground defenses, air defenses, antiaircraft defenses, and naval local-defense forces for Gibraltar, Malta, and Bizerte-Gabes Gulf.

(c) Provide air defenses, antiaircraft defenses, and naval local-defense forces for Oran and Algiers.

(d) Provide ground defenses, antiaircraft defenses, and naval local defense forces for Tripoli.

(3) Ensure the availability of suitable bases required in the Cairo-Suez-Aden area, prior to D-Day.

(a) Provide ground, air, and antiaircraft defenses of the Cairo-Suez area.

(b) Defend the sea approaches to the Cairo-Suez-Aden area.

(c) Provide naval local-defense forces for Alexandria, Port Said, Aden, Massawa, and Port Sudan.

(d) Provide ground, air, antiaircraft, and naval local-defense forces for Crete.

(e) Provide ground, air, antiaircraft, and naval local-defense forces for Cyprus,

(4) Have forces in being on D-Day in Okinawa for the security of that island

(a) Provide ground, air, and AA defenses of Okinawa.

(b) Defend the sea approaches to Okinawa.

(c) Provide naval local-defense forces.

(5) Provide necessary minimum protection for other overseas bases essential to the maintenance of sea and air lines of communication.

(a) Provide ground, air, antiaircraft, and naval local-defense forces for Guam.

(b) Provide antiaircraft and naval local-defense forces for Singapore

(c) Provide naval local-defense forces for bases in Kwajalein, the Philippines, Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand, and Captetown

(d) Provide a theater reserve of ground forces for the western Pacific,

k. Expand the overall power of the armed forces for later operations against the Soviet powers.

1. Provide essential aid to our allies in support of efforts contributing directly to the overall strategic concept.

m. Initiate or intensify psychological, economic, and underground warfare.

(1) Collaborate in the integration of psychological, economic, and underground warfare with plans for military operations.

(2) Provide assistance as necessary for the execution of psychological, economic, and underground warfare.

n. Establish control and enforce surrender terms in the USSR and satellite countries (in the event of a possible early capitulation of the USSR during Phase I).

(1) Move control forces to selected centers in the USSR and in satellite countries.

(2) Establish some form of Allied control in the USSR and in satellite countries.

(3) Enforce surrender terms imposed upon the USSR and its satellites.

(4) Reestablish civil government in the USSR and satellite countries.

23. Phase II. In collaboration with our allies:

a. Continue the air offensive to include the intensification of the air battle with

the objective of obtaining air supremacy.

b. Maintain our holding operations along the general line of discriminate containment, exploiting local opportunities for improving our position thereon and exerting unremitting pressure against the Soviet citadel.

c. Maintain control of other essential land and sea areas and increase our measure of control of essential lines of communications.

d. Re-enforce our forces in the Far East as necessary to contain the Communist forces to the mainland of Asia and to defend the southern Malay Peninsula.

e. Continue the provision of essential aid to Allies in support of efforts contributing directly to the overall strategic concept.

f. Intensify psychological, economic, and underground warfare.

g. Establish control and enforce surrender terms in the USSR and satellite countries (in the event of capitulation during Phase II).

h. Generate at the earliest possible date sufficient balanced forces, together with their shipping and logistic requirements, to achieve a decision in Europe.

24. Phase III. In collaboration with our allies:

a. While continuing courses of action a through/ of Phase II, initiate a major land offensive in Europe to cut off and destroy all or the major part of the Soviet forces in Europe.

b. From the improved position resulting from a above, continue offensive operations of all arms, as necessary to force capitulation.

25. Phase IV. In collaboration with our allies:

Establish control and enforce surrender terms in the USSR and satellite countries.

VOLUME 2. HOLDING THE LAST LINE OF DEFENSE, PREPARING FOR THE COUNTER OFFENSIVE.

STRATEGIC ESTIMATE

I. SUMMARY OF OPPOSING SITUATIONS

1. Political Factors

a. The gravest threat to the security of the Allies within the foreseeable future stems from the hostile designs and formidable power of the USSR and from the nature of the Soviet system. The political, economic, and psychological warfare which the USSR is now waging has dangerous potentialities for weakening the relative world position of the Allies and disrupting their traditional institutions by means short of war, unless sufficient resistance is encountered in the policies of the Allies and other non-Communist countries. The risk of war with the USSR is sufficient to warrant, in common prudence, timely and adequate preparation by the Allies. Soviet domination of the potential power of Eurasia, whether achieved by armed aggression or by political and subversive means, would be strategically and politically unacceptable to the United States.

b. The USSR has already engaged the Allies in a struggle for power. While it cannot be predicted with certainty whether, or when, the present political warfare will involve armed conflict, nevertheless there exists a continuing danger of war at any time.

(1) While the possibility of planned Soviet armed actions which would involve the United States cannot be ruled out, a careful weighing of the various factors points to the probability that the Soviet government is not now planning any deliberate armed action calculated to involve the Allies and is still seeking to achieve its aims primarily by political means, accompanied by military intimidation.

(2) War might grow out of incidents between forces in direct contact.

(3) War might arise through miscalculation, through failure of either side to estimate accurately how far the other can be pushed. There is the possibility that the USSR will be tempted to take armed action under a miscalculation of the determination and willingness of the Allies to resort to force in order to prevent the development of a threat intolerable to their security.

c. In addition to the risk of war, a danger equally to be guarded against is the possibility that Soviet political warfare might seriously weaken the relative position of the Allies, enhance Soviet strength, and either lead to our ultimate defeat short of war or force us into war under angerously unfavorable conditions. Such a result would be facilitated by vacillation, appeasement, or isolationist concepts, leading to dissension among the Allies and loss of their influence; by internal disunity or subversion; by economic instability in the form of depression or inflation; or by either excessive or inadequate armament and military-aid expenditures.

d. To counter these threats to Allied national security and to create political, economic, and military conditions leading to containment of Soviet expansion and to the eventual retraction of Soviet domination, the United States has initiated or is supporting the following measures:

(1) The European Recovery Program.

(2) The development of Western Union.

(3) The increased effectiveness of the military establishments of probable allies.

(4) The North Atlantic Treaty.

e. Alignment of selected states and areas. In order to establish reasonable limits for an estimate of the 1957 alignment of selected states and areas, it has been necessary to reduce the variables involved. Accordingly, the estimate for 1957 is based on the following premises:

(1) Europe and the Near East ["Near East" includes Greece. Turkey, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Egypt, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, British-Arabian protectorates, Transjordan, and Iraq; "Middle East" includes Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Ceylon] will continue as the primary U.S. security interest, and U.S. policy, including the maintenance of West Germany, will remain approximately as now formulated.

(2) The periphery of Asia will continue as an ever-present but secondary U.S. security interest.

(3) Latin America will remain at its present lower priority as a U.S. security interest.

f. The estimate of probable alignment in 1957 of states and areas of the world is as follows:

| State or Area | Probable Alignment in 1957 |

| United States | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Denmark | |

| Norway | |

| Iceland | |

| Greenland | |

| France | Will be allied |

| Benelux Group | |

| - Belgium | |

| - Netherlands | |

| - Luxembourg | |

| Italy | |

| Portugal | |

| Philippines | |

| Canada | |

| Union of South Africa | |

| U.K. Colonial Africa | |

| Belgian Congo | |

| Australia and New Zealand |

| State or Area | Probable Alignment in 1957 |

| Republic of Ireland | |

| Sweden | |

| Switzerland | |

| Greece | |

| Spain | |

| Turkey | |

| Syria-Lebanon* | Will attempt to remain |

| Transjordan* | neutral but will join the |

| Egypt* | Allies if attacked or |

| Arabian peninsula* | seriously threatened |

| Israel* | |

| Iran | |

| India | |

| Iraq* | |

| Pakistan |

| State or Area | Probable Alignment in 1957 |

| Finland | |

| Latvia | |

| Estonia | |

| Lithuania | |

| Poland | |

| Czechoslovakia | |

| Romania | Will be allied with the USSR, |

| Yugoslavia** | either willingly or otherwise. |

| Bulgaria | |

| Albania | |

| Communist China | |

| Manchuria | |

| Outer Mongolia | |

| Korea |

| State or Area | Probable Alignment in 1957 |

| Afghanistan | |

| Non-Communist China | |

| Siam | |

| Burma | |

| Malaya | Will attempt to remain neutral |

| Indochina | but will submit to adequate |

| Indonesia | armed occupation |

| Portugese, Spanish, Italian, and French Colonial Africa |

rather than fight |

| Ethiopia |

| State or Area | Probable Alignment in 1957 |

| Caribbean Area | Will remain neutral or will |

| South America | ally with the United States |

| State or Area | Probable Alignment in 1957 |

| Caribbean Area | Initially occupied as at |

| South America | present or will join the Allies |

*AlI estimates for the Arab states and Israel, with the possible exception of the states on the Arabian peninsula, are fundamentally conditioned by the policies of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Soviet powers regarding Palestine.

** If the present defection of Yugoslavia from the Soviet satellite orbit should continue to 1957, it is not likely that Yugoslavia would ally with the Soviet Union but would attempt to remain neutral and would be committed to resist Soviet and/or satellite attack.

g. USSR and Satellites

(I) Political Aims and Objectives (a) Soviet Union

i. Never before have the intentions and strategic objectives of an aggressor nation been so clearly defined. For a hundred years, victory in the class struggle of the proletariat versus the bourgeoisie has been identified as the means by which Communism would dominate the world. The only significant new facts to emerge have been strict control of world Communism by Soviet Russia and the possibility that the USSR may now be entering an era wherein the ultimate objective might be gained by military force if all other methods fail.

ii. The ultimate object of the USSR is domination of a Communist world. In its progress toward this goal, the USSR has employed, and may be expected to employ, the principle of economy of force. World War III is probably regarded by the Kremlin as the most expensive and least desirable method of achieving the basic aim, but the USSR has been, and will continue to be, willing to accept this alternative as a last resort. As time passes, the intense Soviet concentration on increasing its military potential will render the war alternative less hazardous from their point of view.

(b) Satellite States. In general, the governments of the satellite states which are completely under Soviet domination and control will have no political aims and objectives distinguishable from those of the USSR.

(2) Attitude and Morale

(a) Soviet Union

i. The morale of the Soviet people would not become a decisive consideration to the Kremlin until such time as a drastic deterioration of the Soviet military position took place. While certain elements of the Soviet population—particularly ethnic groups in the Baltic states, [the] Ukraine, the Caucasus, and Central Asia—are dissatisfied with Soviet rule and hostile to domination by the Great Russians, the Soviet government through its efficient security-police network would be able to keep these groups under effective control in the early stages of the war. The more protracted the war, the more chance there would be for these subversive influences, already present in the Soviet Union, to manifest themselves and take a more active part in interfering with the Soviet war effort. Effective resistance or uprisings could be expected to occur only when the Western Allies are able to give material support and leadership and assure the dissident elements early liberation from the Soviet yoke.

ii. Soviet patriotism, while less ardent in support of a foreign war than in defense of home territory, would not be greatly shaken as long as military victories and war booty were forthcoming. As hostilities progress, however, and if Soviet military reverses become known within the USSR, the increased hardships and suffering would magnify any existing popular dissatisfaction with the regime. Russian respect for American technical and industrial ingenuity also might prove to be an important factor in affecting the Soviet people's morale and their willingness to make seemingly useless sacrifices for a sustained war effort.

iii. The people of the USSR are very susceptible to psychological warfare. The Soviet Union's most significant weakness in this regard is its policy of keeping its people in complete ignorance of the true conditions both inside and outside the USSR.

iv. Psychological warfare, therefore, can be an extremely important weapon in promoting dissension and defection among the Soviet people, undermining their morale, and creating confusion and disorganization within the country. It could be particularly effective in subversive operations directed toward those ethnic nationalities which would welcome liberation, as well as toward the Soviet Army, especially those elements of it which would be stationed outside the borders of the USSR.

v. The most effective theme of a psychological-warfare effort directed against the Soviet Union would be that the Western powers are not fighting against the peoples of the USSR but only against the Soviet regime and its policies of enslavement and exploitation, (b) Satellite States. A majority of the native populations in the satellite countries are intensely nationalistic and religious and resent both Moscow domination and Communist regimes with which they are burdened as well as the religious restrictions imposed upon them. This attitude, however, while a source of great potential weakness to the Soviet bloc if shrewdly exploited by the West, would not give rise to effective resistance movements immediately upon the outbreak of hostilities. Initially the dominant attitude among the non-Communist population of the satellite states would be one of increased non-cooperation and passive resistance toward their Communist masters. This would result in some reduction of the agricultural, industrial, and military contribution of the satellites to the Soviet war effort. More effective resistance, however, in the form of organized sabotage and guerrilla activity would be unlikely to develop significantly until they were assured of guidance and support from the West. In view of the probable continuance of these conditions, the peoples of the satellite area in 1957 would still prove readily susceptible to psychological appeals and would be particularly influenced by assurances that aid from the West in support of their aspirations for national independence and religious freedom would be forthcoming.

(3) Political Strengths and Weaknesses. The significant political strengths and weaknesses of the Soviet orbit are estimated to be as follows:

(a) Strengths

i. The native courage, stamina, and patriotism of the Soviet people.

ii. The elaborate and ruthless machinery by which the Kremlin exercises centralized political control throughout the Soviet orbit, employing police forces, propaganda, and economic and political duress,

iii. The ideological appeal of theoretical Communism,

iv. The apparent ability of the Soviet regime to mobilize native Russian patriotism behind a Soviet war effort.

v. The ability of the people and the administration to carry on a war under circumstances of extreme disorganization, demonstrated in the early years of World War II.

(b) Weaknesses

i. Popular disillusionment and embitterment among certain groups throughout the Soviet orbit, resulting from ruthless Soviet and Communist oppression and exploitation.

ii. The fear of the police state pervading all elements of Soviet and satellite society.

iii. The traditional admiration of many of the Soviet and satellite peoples for the living standards of Western democracies in general and of the United States in particular.

iv. Influence of religious groups, especially among the satellites,

v. The native nationalism of the satellite populations and of certain ethnic groups in the USSR.

vi. Probable demoralization which would result from Soviet military and occupation duties in foreign countries.

vii. The extreme concentration of power in the Politburo of the Communist party, which leads the bureaucratic machinery, tends to preclude the assumption of initiative and to discourage individuals at lower levels in the system from making decisions.

(c) It is estimated that the strengths noted above constitute an actual and present advantage to the USSR, while the weaknesses, in most cases, are potential rather than actual. During the early stages of conflict these weaknesses would constitute a substantial burden upon the Soviet Union's machinery for political control and would also impair the Kremlin's economic and administrative capabilities. These weaknesses, however, would not have an early or decisive effect upon the outcome of a Soviet military venture. During the early stages of war native Soviet morale might improve somewhat with reports of spectacular victories and the prospects of

booty from Western Europe. It is unlikely that the psychological weaknesses in the Soviet and satellite structure would produce serious consequences unless the prospect for ultimate victory was seriously diminished by effective Allied air attack, resistance to their advances, disruption of

coastal commerce, and the threat of increasing Allied strength.

(d) Furthermore it is extremely doubtful that the forces of resistance within the Soviet orbit would effectively assert themselves unless they received guidance and material support from the Allies with tangible hope for early liberation by Allied forces.

h. Allied Nations (Except U.S.)

(1) Political Aims and Objectives (a) United Kingdom

i. The United Kingdom desires a maximum of international stability in order to achieve economic recovery as rapidly as possible. However, this aim is qualified by a determination to ensure the security of the United Kingdom, her dependent areas and imperial communications, and the Near and Middle East from Soviet encroachment. The United Kingdom firmly intends, in concert with the United States, to check Soviet expansionism.

ii. The United Kingdom intends to maintain its imperial position so far as possible. In the dependent empire it aims to encourage a reasonable rate of progress toward self-government, replacing political controls with economic, cultural, and security ties, With regard to the Dominions, it aims to preserve and promote Commonwealth solidarity.

iii. The United Kingdom intends to encourage Western Union and increasing unity in Western Europe but at a pace which will not risk the estrangement of the Dominions.

iv, The United Kingdom will continue to support the United Nations. Until the United Nations has the power to guarantee collective security, the United Kingdom will continue to build power-political relationships based on an intimate association with the United States and on the Brussels Pact, Commonwealth cooperation, and the North Atlantic Treaty.

(b) Canada. Canada desires international peace and a high level of international trade as conditions prerequisite to the development of its territory and resources. Canada intends to maintain close relations with the United States as the best guarantee of its security. Canada also intends to continue its membership in the British Commonwealth of Nations, seeing in the Commonwealth a major support of world order and its own participation as a vital link in a North Atlantic security system embracing the United States and the United Kingdom. Canada desires political stability and economic recovery in Western Europe because of the area's importance to Canadian security and because of long-standing cultural and commercial ties.

(c) Australia. Australia desires international peace and a high level of world trade. It wishes to preserve the Australian continent as an area of white settlement and secure it against Asiatic imperialism. It desires friendly relations with the United States and close contacts with the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries.

(d) New Zealand. New Zealand desires peace and a high level of world trade. It desires to preserve the security of the southwest Pacific area and would resist any Asiatic encroachment.

(e) South Africa. South Africa desires to maintain its country free of external influence and internally secure for its dominant white minority. It is interested in seeing as much of the African continent as possible become a "white man's country" in which the Union would be the leading

nation.

(f) France t and Benelux. The primary concern of the governments of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg is security in order to effect the political and economic recovery and stability of their respective peoples. These governments also seek to restore the prestige of their nations to a pre-World War II level and to retain their colonial possessions. All wish to participate in the formation of an economically stable but decentralized West Germany.

(g) Allied Occupied Areas. It is assumed that Allied forces either will be available for D-Day deployment in or will be actually stationed in Austria, West Germany, and Japan in 1957. These countries will, in all likelihood, seek to increase their economic and political strength and will

desire to be reestablished as self-governing states free of occupation forces.

(h) Italy. Italy has two primary objectives: maintenance of political stability through alleviation of economic distress and the resumption of her position as a world power. Two primary considerations keep her aligned with the West, and particularly with the United States, in her attempts to attain these objectives. First is her realization that political stability can be maintained and economic recovery achieved only through very extensive outside assistance and that the West is able to give such assistance. Second is her realization both that her former position as a world power can be achieved only through political alliances and that no alliance with the USSR is possible on any basis of equality or even of independence. While Italy has a history of opportunistic action to fit the needs of the moment, her inborn psychological need for national aggrandizement together with the influence of the church can be counted on to maintain a strong resistance to communization. So long as the Allies can keep her economic distress from becoming unbearable, Italy will remain oriented toward the West.

(i) Iceland. An extreme sense of national independence governs Iceland's political conduct. Although very young as an independent nation, her whole history bespeaks independence of thought and spirit. Culturally, ideologically, and economically, Iceland is closely attached to Denmark, the other Scandinavian countries, and the United Kingdom. Commercial contacts with the USSR have proved highly profitable to Iceland, but the conduct of commercial negotiations was very evidently governed by political and strategic considerations. Iceland's understanding of the purposes and methods of the USSR have prompted her to join in the Atlantic Pact as the surest means of maintaining her independence. She can be expected to cooperate within the Pact to any extent short of compromising her sovereignty.

(j) Portugal. The basic aims of Portuguese foreign policy presently are to ensure the territorial integrity of the motherland and the empire, to maintain the economic stability on which the political stability of the regime depends, and to align Portugal with the Western powers. Realization on the part of the governing classes that Portugal's territorial integrity and economic stability depend on foreign military and political support probably is the basis of the country's signature of the Atlantic Pact. This departure from the traditional Portuguese policy of neutrality apparently was prompted by fears of an advance into Western Europe by the USSR.

(k) Denmark. The ratification by Denmark of the Atlantic Pact marks a significant change in foreign policy but no change in basic political objectives. Those objectives have been, and are, to maintain Danish independence and territorial integrity. For long, foreign policy in pursuit of the basic objectives has been one of strict neutrality and compromise to mutual benefit in relation to the contending great powers. Ratification of the Pact signalizes the realization by the Danes that neutrality, and compromise or accommodation with the USSR, will be difficult. It constitutes a public statement that Denmark is determined to maintain both her political independence and her ideological, cultural, and economic freedom.

(1) Norway. The remarks in the preceding paragraph concerning Denmark apply also to Norway, with, if possible, even more emphasis on the determination to maintain independence and freedom. Since the experience of World War II, Norway has been a leader among the Scandinavian countries in urging and engineering a departure from the traditional policy of complete neutrality and of adopting a policy of formal alliance. The government of Norway is exceptionally stable and it is expected that its policies will remain firm.

2. Economic Factors

a. Soviet and Satellite

(1) Basic Resources

In the overall picture, the USSR has a wealth of raw materials: it has the largest iron-ore reserves in the world, it is second only to the United States in coal reserves, and in 1947 it had proven petroleum reserves of 8 billion barrels. It is self-sufficient in food and most textile raw materials. On the debit side, the Soviet Union and the satellite countries depend entirely or partially on foreign sources of supply for industrial diamonds, natural rubber, cobalt, tin, tungsten, and molybdenum. The satellites are deficient in high-grade ore. USSR steel production by 1957 may reach 32 million tons; the United States in 1947 produced 79.7 million tons. Soviet coal production in 1957 may be 375 million tons, but the United States in 1945 produced 570 million tons. The Soviet petroleum production for 1957 is estimated at 360 million barrels as compared to the United States 1945 figure of 2 billion barrels. While some deficiencies in high-grade gasoline and lubricants may exist in the USSR during the period under consideration, it is unlikely that their war economy will be initially impaired. However, the USSR has a very limited high-octane refinery capacity, which is a significant weakness.

(2) Industrial Development

(a) Following on the present development of the basic heavy Industries, it is expected that the fifth Five-Year Plan ending in 1955 will see a large expansion of the Soviet manufacturing industries with consequent increase in the capacity for armament manufacture. A brake on the speed of her development will remain the capacity of her transport system. In spite of the advances she will have made in all fields of industrial development, her industrial efficiency, technical ability, and productivity will still be considerably lower than that of the Allied nations. This disparity, how ever, may not prevent the USSR from creating conditions of war.

(b) All of the satellite countries have ambitious economic plans, but it is likely that by 1957 only Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Romania will have developed sufficiently for their economic assistance to the Soviet Union to be a significant factor under war conditions.

(3) Industrial Manpower

(a) It is estimated that by 1957 the total population will have risen to 220 million, including a labor force of 90 million. This labor force will include 49 million agricultural workers and a nonagricultural force of 41 million.

(b) The present drive to improve technical education will have begun to show results, and the shortage of skilled workers is likely to be less acute, with the result that an extensive call-up of industrial workers in 1957 would have less effect on industrial productivity than would be the

case in 1949. The supply of unskilled workers will remain sufficient.

(4) Dependence on Foreign Sources for Key Commodities

It is considered that by 1957 the Soviet Union will not be critically deficient in any of the more important strategic materials. In cases such as natural rubber and industrial diamonds, where her productive capacity may fall short of her requirements, she will have made every effort to build up stockpiles, but her success in doing so will be to some extent dependent on the willingness of countries outside the Soviet orbit to meet her requirements in the interim period. The Soviet Union has had good success in importing strategic materials, with the exception of tin. The satellites will continue to require high-grade iron ore from Sweden, but if this were denied to them, the Soviet Union would be able to make good this deficiency, provided the necessary transportation could be made available.

(5) Transport Capabilities

(a) Railroads. It is considered that the railway mileage will have been considerably increased by 1957 and that the system will be more flexible and adaptable to war needs. Nevertheless it will still be insufficient to meet the needs of the greatly increased traffic and there will continue to be a shortage of locomotives and freight cars. The general standard of efficiency will remain low by Western standards.

(b) Motor Transport. Development of long-distance routes is at present concentrated on five main roads radiating from Moscow and on two lateral routes. Progress is slow but by 1957 these routes are likely to have approached Western European standards, and long-distance haulage will afford some relief to rail transport in the west of the Soviet Union. Development of the local road system is likely to have been considerable.

(c) Civil Air Transport. In spite of the improvement in other means of internal transport, it is considered the present reliance on civil air transport is likely to continue.

(d) Inland Waterways. Rehabilitation will have been completed, together with the reconstruction and enlargement of some canals and the completion of new projects. These factors, together with the mass production of metal and concrete barges and the increasing mechanization of cargo-handling facilities, will allow the inland waterways to take an in creased percentage of total traffic and afford some further relief to the railways.

(e) Coastal Shipping. In 1957 the internal transport system of the Soviet Union is likely to remain a comparative weakness in [the] Soviet economy, though in a lesser degree than in 1949. The degree of reliance on coastal shipping in certain areas is therefore likely to persist, and an over

all increase in coastal tonnage is foreseen in the existing Five-Year Plan.

(f) Strategic Significance of Communications. The main strategic strength of the Soviet Union and satellite countries will lie in their possession of interior lines of communications and on their ability to move economic and military traffic without resort to open sea routes. Although great efforts will be made to improve these communications and to over come some of the gauge-change difficulties, the capacity of the Soviet railway system will continue to be inadequate and to be one of the Soviet Union's major economic problems.

(6) Vulnerability of Soviet Industry. Of great strategic importance is the fact that in 1945 nearly 70 percent of USSR petroleum needs were supplied by the vulnerable Caucasus region. New plants being built will reduce this concentration as well as that of the chemical, electric-power, and antifriction-bearing industries, but plants for manufacture of instruments and oil-producing equipment are still located almost exclusively in Moscow and the Transcaucasus complex, respectively. No reliable evidence exists to indicate the development of USSR underground industry. It may be expected, however, that some vital processes relating to jet engines, guided missiles, [and] atomic and biological weapons will be placed underground in small and scattered plants, but such procedures will increase needs for skilled labor and machinery and put greatly increased burdens on the already overtaxed transportation system.

(7) Summary. The industrial capacity of the Soviet Union will have advanced to a considerable degree beyond the 1949 level, and this will be particularly so in the manufacturing industries and hence in her ability to produce large quantities of armaments. Most of the strategic deficiencies prevalent in 1949 will have been overcome, and where productive capacity still lags behind war requirements, stockpiles will have been accumulated. It is in consequence considered that by 1957 the economy of the Soviet Union will be adequate to support her in a major war for a prolonged period,

b. Allied Nations

(1) General. The overall economic potential of the Allies in 1957 will be greater in almost every respect than that of the USSR and her satellites, with productive capacity of essential war industries of the United States and British Commonwealth alone at least twice as great. On the other hand, the occupation of Western and Northern Europe by Soviet forces could yield to the

USSR a number of great long-range economic advantages. The principal gains would accrue to the USSR, however, only after the Soviet Union and the entire area under its control were relatively free from damaging attack and if commercial intercourse were possible with other areas.

(2) United States. The increasing dependence of the United States on foreign sources of strategic and critical materials will probably be the most significant factor influencing the economic position of the United States in the event of war in 1957. This dependence will require consideration of the security of certain overseas sources of supply and of sea and air LOCs [lines of communication] thereto. Our estimated position relative to dependence on foreign sources for strategic and critical materials in 1957 is discussed in the succeeding paragraphs; because of the special importance of oil and the tremendous quantities involved, it is treated separately.

(a) Oil

i. The oil position of the United States has changed from one of abundance to one of critical supply. This position is caused by two principal factors: first, the greatly increased civilian consumption, and second, the diminishing volume of new discoveries and the consequent lag in production sufficient to make up for the increase in consumption. As a result, the United States, for the first time in history, now imports more oil than it exports. Present demand in the United States now exceeds 6 million barrels a day, with production in the United States slightly in excess of 5.75 million barrels a day. Every indication is that United States consumption will continue to mount, with indigenous production unable to keep apace.

ii. In the event of war against the USSR in 1957, the skyrocketing demands of the armed forces will require a production far exceeding the estimated capabilities of the United States at that time. Although it has been difficult to estimate accurately our total requirements—both civilian and military—for a lengthy war beginning in 1957, the best information available indicates that those requirements may reach a maximum of 8 million barrels a day. A factor in such a tremendous increase will be the jet fuel requirements.

iii. In order to meet the greatly increased wartime requirements, the Allies must have access to all Western Hemisphere and Far Eastern sources of petroleum. It probably will be necessary to have access to some, if not all, Near and Middle East oil throughout a lengthy war.

iv. Within the framework of a national petroleum program, measures are being considered with the objective of meeting Allied war requirements without dependence on Middle East supply. These measures include the development of additional sources of natural crude oil, development of synthetics, construction of refineries, substitution of natural gas for non-mobile oil consumers, and stockpiling to an appropriate degree. The degree of implementation of these measures and the results which may be accomplished have not been determined at this time.

v. As an essential step in mobilization, a stringent rationing program and a maximum petroleum-production effort would necessarily have to be instituted. Nevertheless, without successful implementation of the national petroleum program, supplies would be inadequate from the beginning of war if Middle East sources were denied. In summary, adequate supplies for a prolonged war without some Middle East oil are by no means assured, and access to some, if not all, Middle East oil becomes a matter of primary consideration, (b) Other Strategic and Critical Materials

i. The growing dependence of the United States on foreign sources for strategic and critical materials is the result of two significant factors: the first is the greatly increasing demand for these materials as a result of accelerated technological advances in industry; the second is the depletion of mineral reserves and the declining rate of discoveries of new sources of supply in the United States.

ii. During World War II approximately 60 percent, on a volume basis, of our total requirements for strategic and critical materials came from domestic production and 40 percent from imports. On the other hand, for a war beginning in 1957 it is estimated that for the first three years only about 40 percent of our total requirements can be met from United States production, while 60 percent must come from imports and stockpile withdrawals.

iii. Although the United States is currently engaged in a program for stockpiling up to five years' wartime requirements, originally slated for completion in 1951-1952 (minimum stockpile objectives), this program is now several years behind schedule. In addition the current stockpile is considerably unbalanced in that there are little or no stockpiles of some materials and large quantities of others. Nevertheless, by 1957 it is estimated that for many strategic materials, although not all, there will be stockpile supplies for up to five years' wartime requirements.[•Although not considered in this estimate, the condition of the stockpile could be further improved by 1957 by several factors, the principal of which would be the occurrence of a depression or the imposition of mandatory controls on industry.] Unless the United States is cut off from access to foreign raw-material sources, it is unlikely, however, that great quantities will be withdrawn from the strategic stockpile during wartime. This is because a very heavy dependence on the stockpile would be a security risk in the event of a lengthy war, and any major discontinuance of imports would cause serious economic dislocations in the countries comprising our normal sources of supply, which in turn might induce these countries to turn against the United States.

iv. In view of the above considerations and assuming that normal import channels would be kept open, it is estimated that stockpile withdrawals for the first three years of a war beginning in 1957 would average 20 percent of our total requirements.

v. The estimated volume requirements for three years of war beginning in 1957—showing the relative quantities which would be obtained from domestic production, stockpile withdrawals, and imports—is shown in Table 1 below. Table 2 shows the quantities which would be required from each of the various world areas. . . .

vi. The volume figures and percentages shown in Tables 1 and 2 [below] do not present the entire picture as to the actual value of the different areas as sources of supply. Certain strategic and critical materials, while having a low volume figure, have an importance out of all proportion to their actual volume. Based upon a consideration of the actual importance of the principal strategic and critical materials, Table 3 below shows the relative importance of the world areas as sources of these materials during three years of war beginning in 1957. . . .

vii. Withdrawals from stockpiles naturally reduce the requirements of import volumes from the various world areas indicated on the map. Nevertheless, since this estimate is based on the premise that in the event of war, imports will continue, the relative importance of the world areas as sources of supply remains the same whether stockpiles be taken into account or not. For this reason, no separate column has been made for stockpiling in the square representing total U.S. supply in [the] map diagram.

(3) United Kingdom

(a) The United Kingdom is presently in a period of transition from war to peace. She is struggling under a burden of international financial

TABLE 1

ESTIMATED RELATIVE VOLUME OF DOMESTIC PRODUCTION STOCKPILE WITHDRAWALS, AND IMPORTS OF STRATEGIC ' AND CRITICAL MATERIALS DURING THREE YEARS OF WAR, 1957-1959

Total |

1957 - 1959 | |||||

| Short tons | % of Total Supply*** | |||||

| Domestic Production | 20,400,000 | 40 | ||||

| Stockpile Withdrawals | 10,000,000 | 20 | ||||

| Imports | 20,600,000 | 40 | ||||

| Totals | 51,000,000* | 100 | ||||

| ST** | %TS** | St | %TS | ST | %TS | |

| Domestic production | 6,800,000 | 49 | 6,800,000 | 40 | 6,800,000 | 34 |

| Stockpile Withdrawals | 2,700,000 | 19 | 3,000,000 | 18 | 4,300,000 | 22 |

| Imports | 4,500,000 | 32 | 7,200,000 | 42 | 8,900,000 | 44 |

| Totals | 14,000,000 | 100 | 17,000,000 | 100 | 20,000,000 | 100 |

*Except for bauxite and cobalt, minerals included in this estimate represent metal content in ore. Minerals comprise about 84 percent of total supply requirements of strategic and critical materials.

**tST means "short tons"; %TS means "percentage of total supply."

*** Rounded figures.

TABLE 2

ESTIMATE OF U.S. AVERAGE YEARLY VOLUME OF STRATEGIC

AND CRITICAL MATERIALS FROM VARIOUS WORLD AREAS

DURING THREE YEARS OF WAR, 1957-1959

| World Area | Average Yearly Volume Short Tons | % of Total US Supply | % of Total Imports |

| South America | 3,864,500 | 22.8 | 56 |

| Africa | 1,484,500 | 8.8 | 22 |

| Canada | 804,500 | 4.7 | 12 |

| Mexico-Caribbean | 294,500 | 1.7 | 4 |

| Southeast Asia | 294,500 | 1.7 | 4 |

| Australia-Oceania | 124,500 | 0.7 | 2 |

| Totals | 6,867,000 | 40.4 | 100 |

TABLE 3

ESTIMATED RELATIVE IMPORTANCE TO THE U.S. OF WORLD AREAS

AS SOURCES OF STRATEGIC AND CRITICAL MATERIALS

DURING THREE YEARS OF WAR, 1957-1959

| World Area | Percentage of Total Contribution to the US |

| US, domestic production | 28 |

| Imports, by world areas | 72 |

| South America | 16 |

| Africa | 16 |

| Canada | 5 |

| Mexico-Caribbean | 13 |

| Southeast Asia | 13 |

| Australia-Oceania | 9 |

| Total | 100 |

| Western Hemisphere | 62 |

| Eastern hemisphere | 38 |

and domestic economic problems, a serious manpower shortage, and political instability in the empire. It is unlikely that the United Kingdom will be able to finance another war effort as great as the last one.