Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

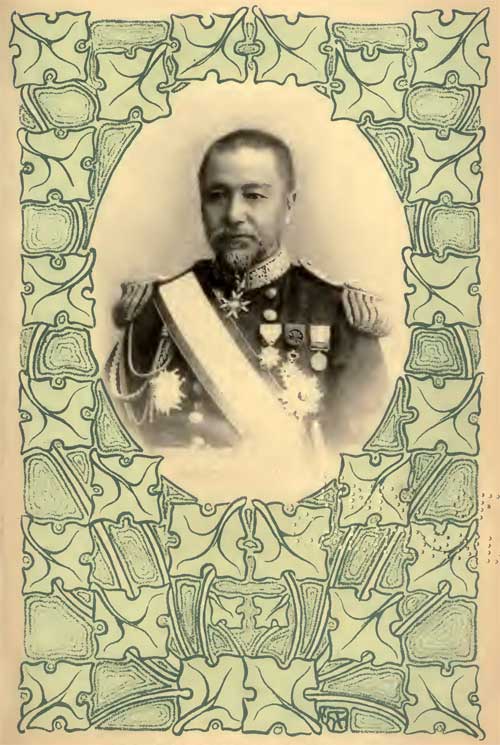

THE LIFE OF ADMIRAL TOGO

by Arthur Lloyd, M.A.

For the imperfections of the present volume I can only plead that I hope it may prove to be a first edition, and that further studies and the publication of more detailed information may enable me at some future time to complete, or at least to elaborate, the biography of a great man in whom the whole world is interested.

The modest and retiring life which Admiral Togo has hitherto lived has made it difficult for the biographer to collect many picturesque incidents relating to his early years. But modesty is one of the greatest of virtues, and that he has always exhibited this virtue in so conspicuous a manner seems to be one of the elements which make the greatness of his character.

ARTHUR LLOYD.

Tokyo. August, 1905.

THE LIFE OF ADMIRAL TOGO

I. The Beginnings of Japan's Naval History

If we were writing an account of the naval history of Great Britain, we should probably choose as our starting-point the history of the Spanish Armada and its signal overthrow in the sixteenth century.

This choice of a starting point would not imply that there is to be found no sea-fighting in English records of an earlier date. An island- kingdom like England must always have been both vulnerable and defensible along her coastlines and harbors, and Englishmen have all through their history been fighters on the sea. But the Spanish Armada first demonstrated to Englishmen the prime importance of a standing fleet as a permanent wall of defense, and the creation of the British Navy was the logical outcome of the defense hastily organized against the fleets of Spain, in spite of the fact that the civil troubles, which, in England, followed so soon after the destruction of the Armada, interposed some years between the recognition of the need and the creation of the Navy.

Japan, a sea-girt land, had a warning of possible danger, from an invasion by sea many years before England received hers, and though the civil troubles which supervened in Japan were of far longer duration than those in England, and though Japan had to wait in consequence much longer than did England, before she became a naval Power, yet the logical birthday of the Japanese Navy was so very much like the birthday of the British naval Power that I cannot help commencing my book with it.

The British Navy was practically born when the Lord High Admiral of Queen Elizabeth was commanded to equip a fleet as best he could to repel the threatened invasion of the Spaniards. The Japanese Navy may also be said to have been born when Hojo Tokimune the Regent, in 1275, took his measures for repelling the Mongolian invasion.

Kublai Khan, the great Mongolian leader of the Middle Ages, had succeeded in overthrowing the Sung Dynasty in China and making himself master of the whole of the Celestial Empire. He had further reduced to submission the entire peninsula of Korea, and having reached the extreme limits of the Asiatic mainland, began to cast covetous eyes towards the beautiful and happily situated islands which form a defensive barrier for the eastern shores of that Continent.

Koppitsuretsu (to give him his Japanese name, Kublai Khan being the name by which Europeans know him better through the writings of the famous Venetian, Marco Polo), — Koppitsuretsu doubtless thought that Japan would be an easy prey for his armies. There was every reason to make him think so.

Never was a country more extraordinarily governed, or misgoverned, than Japan in the thirteenth century. A series of long intrigues within the court brought about a succession of abdications, forced or voluntary, which frequently left the occupant of the throne a mere shadow of Imperial dignity. The actual functions of the executive were in the hands of a Shogun, who was supposed to act in all things as the Emperor's representative; but similar intrigues in the entourage of the Shogun reduced this high functionary to a mere " puppet" in the hands of his retainers, one of whom, residing at Kamakura, acted as his representative, with the title of " Regent." Western readers will scarce believe me when I say that, in the Hoj5 family, a custom arose of having nominal " regents" as well, but they will not be astonished to be told that, under this extraordinary system of carrying on affairs of state, the whole country was in anarchy and confusion, and every one did practically what was good in his eyes. The Buddhist priests reaped a temporary harvest of wealth and influence from the system, which was one of their own creating, but even in the ranks of the priesthood voices were raised against the misgovernment of the times, and the life of Nichiren, the most picturesque of Buddhist reformers, is full of the troubles which his vigorous protests brought upon him.

Under these circumstances, we cannot wonder that Kublai Khan, elated with his conquests in Korea and China, should have fallen into the error of under-estimating the pride and strength of the Japanese people. He wrote a letter couched in insolent terms, to the reigning Emperor (Go-Uda Tenno 1257—1287), demanding submission and tribute from the Empire of Japan, but his insolence overshot the mark, . The Regent of the time, Hojo Tokimune, though quite a young man, was proud and high spirited, and had no hesitation as to the course to be adopted. He sent the Korean envoys of the Mongolian conqueror back to China with scornful words, which he showed to be deliberately chosen by repeating them to a second embassy sent in the following year.

Kublai Khan was too great a potentate, and had been too openly defied, to sit down tamely under the insults of the Japanese. He collected an army in Korea which he embarked on board a fleet of 450 Korean war junks, seized the islands of Iki and Tsushima, which have played so great a role in the present war against Russia, and landed on the coasts of Kyushu, where he was, however, repulsed by the Japanese, after desperate fighting. This was in 1275 : three years later Kublai Khan sent another ambassador, and yet another, to Japan, urging the Island Empire to submit and send him tribute; but Tokimune beheaded them both.

The result was that Kublai Khan, deeply insulted, vowed a tremendous vengeance against the insolent islanders, and prepared armies and fleets far greater than those he had sent before. It was a critical moment for Japan. The people were moved with a mixture of anger and apprehension; Nichiren preached and wrote, exhorting, reproving, and urging much-needed social reforms; the Emperor went in state to the Temples at Ise to pray to his ancestress, Amaterasu, goddess of the sun, for help against the enemies of the country; Tokimune talked little but collected an army and went forth to battle. The Mongols had landed and were encamped near Takashima, where Tokimune attacked them, and, after desperate fighting, drove them back to their ships. Then came an interposition of the Divine Providence which has so frequently manifested itself in the affairs of Japan. Scarcely had the Mongol troops found refuge on board their ships when a terrible storm arose and destroyed their whole fleet. (A.D. 1281).

Many readers have seen the obvious parallel between the Mongol Invasion of Japan and the Spanish Armada. Many have also seen the obvious similarity between the Mongolian Invasion and the Russian Expedition from the Baltic. This is not the case to discuss these similarities. What I wish to say here is that as the Spanish Armada had its logical outcome in the creation of a standing Navy, so the logical outcome of the Mongol Invasion was the Navy of Japan to-day.

In each country, a threatened invasion demonstrated the absolute importance of a Navy as a first line of defense. In England, where the internal troubles were fortunately of short duration, little more than fifty years elapsed before the fleets of the Commonwealth were busy defending the interests of England against the navies of France and the Dutch Republic. In Japan where the evils of state and society were far more deep- seated, and where the civil dissensions, followed

by the iron repression of all activity by the Tokugawas, lasted for well-nigh six hundred years, the logical outcome of that lesson was correspondingly long in being realized.

But assuredly the lesson was given in Japan as well as in England. If Providence interposed in the two cases to work signal deliverance, it was not to encourage either nation to a blind trust in Providence in the future. God helps those that help themselves, and the obvious lesson which both nations were meant to learn, and have learned, is that island-empires need floating-walls to protect them.

For the practical realization of the Japanese Navy we must jump over a period of six hundred years from the Mongol Invasion to the middle of the nineteenth century when the day was rapidly coming for Japan to come out of her seclusion to play a part in the world worthy of her dignity and providential mission. We call it her providential mission, because if the hand of Providence was clearly to be seen in the wonderful deliverance from the Mongols, the thoughtful student may also see the traces of the same hand in the seclusion from the world which followed the establishment of the Tokugawas, (a seclusion the maintenance of which was little less than marvelous) and the timely emergence of the nation, as of a people born in a day, to bring a new element of life and vigor into a civilization which was beginning to suffer from senility and decay.

The nineteenth century made it impossible to maintain any longer the seclusion of Japan. The trade of Europe was expanding, the civilization of America had emerged on the Pacific coast, Australia had been discovered, steam was revolutionizing navigation. From all sides ships came past the coasts of Japan, some desirous of traffic, some for water and help, some to restore castaway Japanese fisherman. Intercourse became unavoidable, and many of the patriotic Japanese feared that intercourse would mean the loss of national independence.

Amongst those who felt much anxiety on this subject was Prince Shimazu, lord of Satsuma, one of the most powerful of Japanese Princes, and one whose territories, situated in the extreme South and West of Japan proper, gave him much cause for anxiety on this subject. Satsuma was by no means the only Baron who felt anxiety on this point. The lords of Mito and Tosa, nay, even the Shogunal Cabinet itself were much exercised about it, and at last in the year 1847, after much deliberation and debate, a resolution was come to by the Shogunate, not only to undertake the work of Naval Organization itself, but to allow the great territorial nobles, who ruled as kings within their own dominions, to raise squadrons for the defense of the seaboard of Japan. The Prince of Satsuma was one of the first of the Daimy5s to avail himself of this permission. The Satsuma fleet was soon one of the most powerful of the local fleets. We shall find the Prince petitioning the Central Government in 1853 for permission to build not merely small vessels for coast-defense, but large ships capable of keeping the sea and pursuing a retreating enemy. We shall find him later on sending up to the North a Fleet capable of engaging the Shogunal Navy under Enomoto, which was making its last stand at Hakodate. We shall also see the Satsuma Fleet emerging victorious from these engagements and so becoming, in the new era which dawned upon Japan after the war o the Restoration, the nucleus of the present Imperial Navy of Japan Admiral Togo's first sea-service was in the Satsuma Navy t his subsequent career has been with the Imperial Navy from its very commencement This history of his life is there fore very much a history of the Imperial Navy of Japan, with which he has been so long and so constantly identified. But, before writing it, it will

be well to devote one more preliminary chapter to the consideration of the Satsuma Daimyate which has furnished so many of the best men to the services of the Japanese Empire.

Madam Tetsuko Togo

CHAPTER II. Satsuma

The ancient Daimyate of Satsuma, ruled over by princes of the Shimazu family, occupied the southern portion of the Island of Kyushu, i.e. the whole of the provinces of Satsuma and Osumi, together with portions of Hyuga, and several islands off the coast. The Lord of Satsuma was also in a sense a suzerain of the Loochoo Archipelago, for the ruler of those islands acknowledged a double dependence, and sent tribute not only to China but also to Satsuma.

The Satsuma Daimyos had always been very powerful, and their overlordship had extended itself on various occasions over the greater part of the island of Kyushu. They had also been for long years practically independent of the Central Government in the days before the Tokugawa regime, and when, after the pacification which followed the battle of Sekigahara, Shimazu was obliged to bow his head before Iycyasu, he had done it with a bad grace and a reluctant heart. The Satsuma people had always resented the Tokugawa supremacy, and, living as they did in a very remote corner of the Empire, had always contrived to have a tolerably free hand in the management of their own affairs.

The Satsuma samurai were always noted for their poverty. Their numbers were far greater, proportionately to other daimyates, in Satsuma than elsewhere, and the provision of rice, which it was the custom for all daimyos to give for the support of their retainers, was constantly, in Satsuma, insufficient for the support of the whole body of samurai. The samurai ot this province, therefore, came in time to be distinguished from those of other provinces by their industry and thrift. They were obliged to work as farmers to eke out their allowances, they were obliged also to exercise the most rigid economy in the management of their households. They became, therefore, a sturdy race not unlike the English yeomen of the middle ages, frugal, active, and independent, and whilst the samurai of other, more wealthy, daimyate were all succumbing more or less to the enervating influences 01 ease and freedom from pecuniary cares, the Satsuma men, like the Spartans in Greece, stood out conspicuously among their compatriots for simplicity, hardihood and practical common sense.

The country round Kagoshima, the capital of Satsuma, is admirable training ground for soldiers, and the Satsuma samurai were constantly, even in times of peace, kept at work with military maneuvers and exercises of various kinds. Hence the Satsuma armies had always been vigorous and hard to beat, though the same might be said of the local armies maintained by many of the Japanese princes. East or West, North or South, the Japanese has always shown himself to be an excellent fighter.

But Satsuma, owing to its geographical position and political circumstances, had one advantage over all other daimyates. It had a long and dangerous seacoast, a deep, protected, bay whose calm waters afforded excellent opportunities for nautical training, and its Prince was one of the overlords of Loochoo, a position which necessitated maritime journeys such as fell to the lot of the subjects of no other daimyate.

Thus, even in the Tokugawa days, when all commerce by sea was forbidden, the Satsuma people were a sea-faring folk.

The spirit which animated the Satsuma samurai may be seen from the following account which is given of the training of the young Kagoshima retainers.

Every village in the province had its own Gochu or village association of young men, and every young samurai was enrolled a member as soon as he reached the age of 14 or 15. The object of the Gochu was to encourage bravery, and the power of endurance, and its members were constantly being tested by their seniors and associates with a view to ascertaining their qualifications in this respect.

If a young man, on being tested, showed signs of fear," he received a warning from the senior members. If, on his next trial, he did better, he was forgiven and nothing more was said. If he " funked" again, however, then woe betide him. He was cut off from the society of young men, and no sentence of excommunication could possibly be worse than such exclusion.

Every member of a Gochu had to study for eight hours a day, four morning hours being devoted to "books," and four in the afternoon to practical exercises. On the 1st, 6th, 11th, 16th 21st, and 26th of every month they practiced writing, the 5th, 10th, 15th, 20th, 25th, and 30th were given to the reading of books on military subjects, the remaining days were in like manner devoted to subjects likely to be of practical use in the training of a warrior caste. They had not many subjects and no useless ones, the few they had were thoroughly practical, and thoroughly well learned. Any neglect or violation of the rules of study was at once punished by the Gochu. We can see the traces of this custom still in the way in which members of the old samurai caste will throw themselves into the study of some special branch of practical science.

The Gochu had certain festivals of their own, not religious but patriotic, for patriotism with them took the place of religion. The Revenge of the Soga Brothers, and the tragic death of the Forty Seven Ronins, two of the most famous vendetta stories of mediaeval Japan, were celebrated with simple but appropriate ceremonies, the one on May 18, and the other on December 14. On these occasions the accounts of these heroes of olden times, and their deeds were represented in song and mime, and their youthful hearts were moved to compassion or admiration as the different scenes of the tragedies fell on their ears. Thus we can imagine a gathering of Jewish lads to have been moved by the narrated prowess of Jephthali, Gideon, or David, or a class of Athenians roused to anger or melted to tears over the Iliad or the Odyssey. It is the story of men of one's own blood that appeals most strongly to the human heart.

It has been noted that the Shimazus needed no strongly fortified castle to keep their retainers in subjection. Contented and loyal subjects are the best possible bulwarks of a throne, and such were the retainers who surrounded the Lords of Satsuma.

We can understand now the moral atmosphere in which our hero was born and educated. Simple living, stern discipline, high thinking, if withal, somewhat narrow. In the moral and political regeneration of Japan, Satsuma (allied to Choshu and one or two other daimyates) played the part which Prussia did in Germany, or Sardinia in Italy. The Shdgunate, like Austria in the one case, or Pio Nono in the other, clung loyally but blindly to a lost cause trying in vain to bolster up a political system which had outlived its day and become a hindrance to the healthy growth of the nation. The motives were of the highest order, the patriotism of the defenders of these lost causes was in every case most admirable, but the causes were lost from the beginning, and their defenders were overwhelmed in the fall of the ramparts behind which they stood. Like Prussia, the men of Satsuma saw beforehand the crash that was inevitably coming, and took their measures to champion the true political creed on which alone Japan's greatness could be based. The overthrow of the Shogunate and the restoration of the executive power to its proper possessor were both measures of inevitable necessity, and if from their timely advocacy of these measures the men of Satsuma and Choshu "sucked to themselves no small advantage," still the advantages to Japan as a whole have been still greater, and no fair-minded critic will be disposed to grudge them their position of honour in the councils and enterprises of the nation. Palmam qui meruit ferat.

CHAPTER III. Togo's Birth and Early Education

Togo Heihachiro was born in Kajiya-machi, the Samurai quarter of Kagoshima, on the 22nd of December, 1847.

His family was descended from the ancient family of the Taira, which played so great a part in the Middle Ages of Japan. The last and, indeed, the only sage of the Taira family, Taira no Shigemori, had an only daughter, who, on the ruin of her house, being pursued by her enemy, the head of the rival Minamoto family, found an asylum in the territories of the Prince of Satsuma. Here she remained, educating her children, who, growing up, entered the service of the Satsuma Daimyo and were granted the surname of Togo. It is said that this remote ancestress of the Togo house had, for reasons probably connected with the circumstances of her escape from the Minamoto, an aversion to riding on a white horse, and this tradition is said still to remain of force in the Togo family. In the garden attached to the old family homestead in Kagoshima, now unfortunately destroyed by fire, there stood during Togo's boyhood a small shrine sacred to the memory of the first ancestress of the family.

. The future Admiral's father, Togo Kichizaemon, had a great reputation for probity and justice. He held the responsible office of Kori Bugyo or District Magistrate—an office not unlike the honorable post of Justice of the Peace which is the pride of many a country gentleman in England,—and discharged his difficult duties so well, that, at the request of his fellow-townsmen, he continued to hold it for thirteen consecutive years, though the usual period of tenure is only for three. His character was very much like that of his illustrious son—simple, straight-forward, somewhat taciturn, but kind and sincere. He was not a diplomat, but there was something statesmanlike about his straight-forward simplicity.

His mother, Masuko, is said to have been a fine-looking refined lady, the very type of woman that Kaibara Ekiken, the author of the celebrated Onnadaigaku ("Great Learning for Women"), would have delighted to describe. She was frugal and orderly, an excellent house-keeper, and moreover, a splendid disciplinarian. She trained her children as' a Spartan mother would have done, and was a convinced believer in the old saying about the devil and the idle hands. She constantly kept her children busy with their studies and military exercises, and allowed them very little leisure in which to get into mischief. She had four sons, of whom Heihachiro was the third. The Admiral's three brothers all took part in the rebellion of the elder Saigo, and perished at the battle of Shiroyama. Fortunately for Heihachiro he was studying in England at the time, and out of reach of temptation.

In due course of time, Heihachiro, like the other lads of Kagoshima, entered a G5chu. The Gochu into which it was his good fortune to enter was one with an exceedingly good record. The elder Saigo, the flower of Japanese chivalry, had once been in its ranks: and one of T5gd's boy companions and contemporaries was Kuroki, destined like himself to win distinction in war with the Russians. One of Saig5's younger brothers was Togo's teacher of Chinese, and read the Confucian Analects with him. It was Togo's habit to rise early, before sunrise, and to stand at his teacher's gate till six o'clock, when he was permitted to enter and receive a lesson of two hours' duration. From eight o'clock till noon he was busy reviewing the lessons he had learned with his teacher, and the afternoon was spent, sometimes in study and sometimes in fencing and wrestling with Kuroki and other companions by the riverside.

As a boy, he was always noted for his quiet peaceable disposition. He very seldom concerned himself in the quarrels which took place between the different Gochu in the city, and rarely had any quarrels of his own on hand. Yet he always contrived to hold his own amongst his comrades, who deferred to him as boys do to one in whom they see a capacity for leadership, even though he takes no step to assert himself, or to lord it over his comrades.

In 1863, at the age of seventeen, Togo entered the Satsuma Navy, as a cadet. It has been said that the real cause of the establishment of that Navy was fear of Russia, whose aggressions were even then known and dreaded by Japanese Statesmen. We have also heard it maintained that when, shortly after the Imperial Restoration, the elder Saigo was led astray into rebellious paths, his moving reason was not a dissatisfaction at the comparatively small amount of recognition given to Satsuma in the Imperial Councils, but a desire to see a more resolute policy against Russia adopted by Japan, together with a resolution to get the power into his own hands, so as the better to prosecute a line of policy which he felt to be of vital importance to his country.

Be that as it may, the first foreign enemy to be encountered by Japanese armies was not Russia, but England. The discontent with which patriotic Japanese saw the sacred soil of their country defiled by foreign feet, together with the growing lawlessness of the times, made it impossible for the authorities, national or consular, to avoid all disturbances between Japanese and foreigners. Outrages against the barbarians were of frequent occurrence: attacks were made upon the British Legation in Yedo, ships passing through the Straits of Shimonoseki were fired on by the fortresses of the Prince of Choshu, and one incident in particular occurred, which brought Satsuma, individually, into trouble with the English authorities. A troop of Satsuma retainers who were accompanying the uncle of their Prince on his way to Yedo, on the 14th of September 1862, attacked a party of foreigners riding peaceably along the high road near Kanagawa, and murdered one of them, an Englishman named Richardson. The British authorities promptly demanded satisfaction from the Shogunate, but, whilst getting an indemnity from the Yedo Government, were referred for full satisfaction to the Prince of Satsuma, as the feudal lord of the men who had made the attack, and as being, therefore, a responsible party in the affair. Satsuma, while deeply regretting the incident at Namamugi (the hamlet at which the attack was made), and willing to pay a money indemnity for the thoughtless act of his turbulent retainers, absolutely refused to hand over the perpetrators of the crime to the English, as they desired. Some delay occurred over the negotiations, but at last, in August 1863, an English Squadron arrived in the Bay of Kagoshima, and, failing to get its demands satisfied, proceeded to bombard the town. The engagement took place on the 15th August 1863. The Kagoshima authorities were much surprised by a visit which they hardly expected. They were still more taken aback, when the English summoned three vessels belonging to the Satsuma Navy, which they found at anchor in a remote corner of the bay, to shift their anchorage, and take up a new position in the midst of the British Squadron, an order which the Japanese vessels obeyed without apparently knowing what it meant. This action the Japanese claim to have been a treacherous one on the part of the British ; but the British, on their part, thought they had just cause for complaint, when, at the stroke of noon, without any previous warning, the Kagoshima forts opened fire on their unwelcome visitors. A fierce cannonading then ensued, which did much damage without leading to any very tangible results. The weather was boisterous and stormy so that the British could not have landed a party of men even if they had had the force requisite for the operation. They burned the three Satsuma vessels and reduced a large portion of the town to ashes, but without silencing the forts. On the other hand, they suffered severely themselves : one of their ships went ashore and only got off with the loss of her anchor, which was afterwards restored by the Japanese; and there were many losses both of officers and men. The next morning they sailed out of the bay, to avoid a threatening typhoon, leaving behind them an indecisive record. They had reduced the city to ashes and destroyed a part of the fleet of Satsuma; but the forts were never silenced, and they sailed away without having got their demands. The indemnity was paid in September 1863, but the Satsuma authorities never surrendered the persons of Richardson's murderers.

The bombardment of Kagoshima was Togo Heihachiro's baptism of fire, and Japanese writers tell us, with great pride, how the future Admiral, stripped to the skin, was working at the guns in one of the batteries on that eventful day.

It is worthy of note that on this day the Japanese fired the first shot, without waiting for any formal declaration of hostilities. We remember as we write down the fact that it was Togo as Captain of the Naniwa, who sunk the Kaosheng in the war with China, and Togo who, as Admiral, ordered the discharge of the first torpedo against the Russian vessels at Port Arthur. In neither case had hostilities been declared when the first shot was fired. Can it have been Togo who applied the fuse to the first gun fired at Kagoshima ?

The Satsuma Navy covered itself with glory in this action. It had held its own in a fair fight with a British Squadron, and had lost nothing except the three steamers which had been taken by surprise, and placed as it were hors de combat before the action commenced. But the bombardment had the effect of arousing the whole nation to the need of naval armaments. The Shogunate, Satsuma, Choshu, and perhaps one or two more daimyates had hitherto been the only ones that paid any attention to coast defense, but now the whole nation was roused to action. Even the Emperor[*] bestirred himself and bade his subjects sweep the Kurofune (black ships) off the sea." Many small navies made their appearance in different provinces, but none could compete with the Navy of Satsuma which had been in action with foreigners, and, had passed safely through the ordeal. The Choshu ships did not come out so well in their conflict with the foreign vessels at Shimonoseki. But then Choshu s glory has always been great in the army.

[*] I have seen a poem by Komei Tenno, the father of the present Emperor, which runs somewhat like this :

" Perish my body in the cold clear depth Of some dark well, but let no foreign foot Pollute that water with its presence here."

The next few years were uneventful years in the history of the Satsuma Navy: years of preparation for great events generally are. Nothing much is known of our hero during this period, except that he continued to serve with diligence in his profession, and that he gained a reputation as an excellent officer, silent and unobtrusive, but quick in decision and decisive in action. It was evident that the Revolution which was to put the Mikado in his proper position, and place the men of the South on the top of those of the North, was coming on at a rapid pace, and Togo must often have heard, and perhaps sung, the verses in which San-yo Rai describes the Satsuma Bushi.

1. Short are our skirts — down to the knees: and short our sleeves—just to the elbow.

2. At our hips are our swords that can cut through iron:

3. If horse touch them or man touch them, they will kill him at once.

4. The youth of eighteen enters the Society of the strong Youths:

5. If a visitor comes from the North, with what shall we entertain him?

6. Bullets and powder shall be the tables and dishes;

7. And if, perchance, the visitor should not relish them,

8. The sword over his head shall give a closing dish.[*]

[*] Koromo wa kan ni itari, sode wan ni itaru : Yokan no shusui tetsu tatsubeshi; Hito furureba, hito wo kiri, uma furureba uma wo kiru. Juhachi majiwari wo musubu, kenji no sha: Hokkaku yoku kitaraba, nani wo motte ka mukuin ? Dangwan shoyaku kore zenshu : Kaku moshi shoku-en sezumba, Yoshi hot5 wo motte kare ga kobe ni kuwaen.

CHAPTER IV. The Civil War at the Time of the Restoration. 1867-1869

We next find Togo at Kyoto in the year 1867. Satsuma and Choshu men had made good their claim to be the protectors of the Imperial person, and driving out from Kyoto the rival Tokugawa clans, and the men of Hikone and Aizu, had occupied that city in force. The Shogunate Government, general known as the Bakufu, had been abolished, and an Imperial Government at Kyoto proclaimed in its stead.

The Tokugawa party were thoroughly discontented. Riots broke out in Yedo which the Shogunal police were unable to quell. The Satsuma-yashiki at Mita was burnt to the ground, and the Satsuma adherents in the stronghold of the Tokugawas escaped with difficulty to Shinagawa, where they were taken on board a small vessel, the Kuslid Maru. One of the Shogunate warships, the Kwaiten Maru, commanded by Enomoto Kamajiro, went in pursuit, and after a desperate fight, in which the crew of the Kosho plugged the shot-holes in the hull with their own clothes, succeeded in doing her so much damage that the Satsuma men were

obliged to abandon her, and only managed to join their own men at Kyoto with great difficulty.

When the Shogun heard of the troubles in Yedo and the burning of the Satsuma-yashiki, he at once petitioned the Emperor for permission to chastise the men of Satsuma, and then, without waiting for a permission which he had very little chance of getting, marched from Osaka, where he was staying in the Great Castle of the Tokugawas, with all his forces for Kyoto. But the men of the " Four Loyal Clans," Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa and Higo, marched out to meet him, a battle was fought at Fushimi (28 January 1868), and the Shogun, defeated and a fugitive, appeared at Hyogo, where he was taken on board an American man of-war, which afterwards transferred him to the Kaiyo Maru, one of his own vessels. This ship, of which Enomoto was made Captain, conveyed the Shogun to Yedo.

When the Kaiyd Maru had been coming down from Shinagawa to Osaka and Hyogo, to look after the interests of the Shogun, she had met two Satsuma transports carrying troops from Kagoshima for garrison duty in Kyoto, and had fired on them as they left that port. This was before the battle of Fushimi. The transports at once returned to port and gave information. A protest

followed, but the Shogunal authorities justified the action of the Kaiyo Maru in firing on the transports. Satsuma and Yedo were practically at war, they said, and there had already been some fighting off Shinagawa.

The Satsuma men were obliged, therefore, to take measures of self-defence. They had no ships of war with them, but the Kasuga Maru was lying off Kobe, out of commission, it is true, but still available for convoy service, if she could be fitted out.

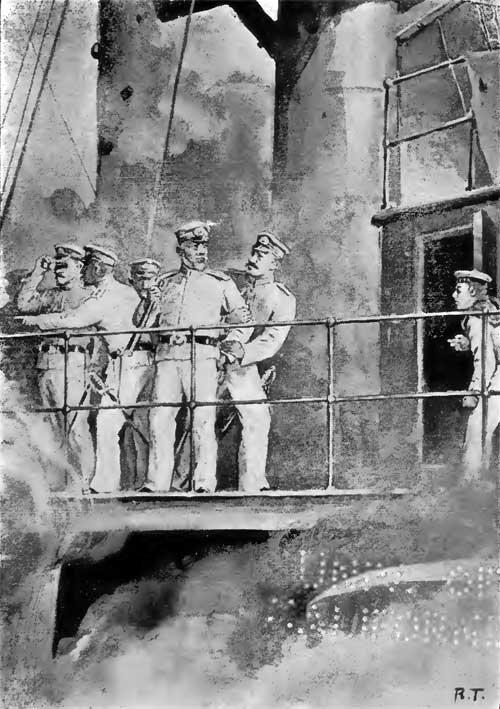

This was done with all speed: the ship was hastily prepared for sea, and manned from the troops brought up by the transports. The Satsuma garrison in Kyoto was able to furnish the officers. Akatsuka Genroku was appointed Captain, Ito Sukemaro (the elder brother of the Admiral) vice-captain, and Togo Heihachiro one of the junior lieutenants.

As soon as the ship was fitted out she was brought round to Osaka. The Shogun's ship was not to be seen, so the transports started on their journey to Kagoshima, with the Kasuga Maru to convoy them. Presently, off the coast of Awa, the Kaiyo Maru was seen coming through the clearing mist, close to them: and the Kasuga Maru, in spite of her imperfect equipment and scratch crew, at once engaged her. The fight lasted for some time, without any very serious loss on either side, then, suddenly, the Kaiyd Maru sheered off and returned to port, and the Kasuga Maru hastened on to look after her transports, which had now reached a place of comparative safety.

This engagement took place on the 3d day of the 1st month (old style) of the year 1868. Togo distinguished himself by his activity in helping to get the crew together and the ship ready for action, as also by his coolness under fire. His superiors saw him to be a steady man on whom they might rely,—and these are the men who succeed in making a name for themselves. The action was not a very great one, but it gave the Satsuma men an opportunity of proving their metal, and in the action Togo did his duty.

The Civil War had now broken out, and the Tokugawa party found one of its staunchest supporters in Enomoto, whom we have already seen as Captain of the Kaiyo, but who will now appear as the Admiral in command of the Shogunal Fleets.

The victory at Fushimi was only the first of a series of successful actions, which- gradually brought the whole island under the rule of the Emperor and his forces, and during the summer of 1868, the Shogun was ordered to deliver to the Emperor the Castle of Yedo, and all his forces military and naval. To this order the Shogun complied as far as he could, but his retainers were far more active in his support than he was himself, and Admiral Enomoto, on receiving the order to surrender his ships, quietly sailed out of Shinagawa Bay, with 11 ships, at early dawn on Aug. 22 1868, and took himself north to Hakodate, where some of the northern daimyos were still under arms for the lost cause of the Shogunate.

A landing was made at Hakodate, the loyalist daimyo of Matsumae was defeated at Esashi, a temporary Government was established, and measures taken for a prolonged resistance. Enomoto's fleet was a factor of prime importance. He had eleven ships in all: his opponent had only four or five; and, with Hakodate as his base of operations, he might be a terrible thorn in the side of the newly restored Imperial Government.

The Imperial Government at once took action to crush the Hakodate scheme. A force of 6500 troops was hastily dispatched north, together with a squadron under the command of Akatsuka, whom we have already seen as Captain of the Kasuga Maru. Togo was still serving on board the Kasuga, which was now in better trim than it had been for the hastily planned engagement off the coast of Awa, and the Loyalist Fleet was strengthened by the addition of a new iron-clad war vessel, the Stonewall Jackson, recently purchased from the American Government by the Shogun's Government, and waiting in Yokohama to be delivered. Since giving the order, the Shogun's Government had collapsed, and there being apparently no other person authorized to take delivery, the American Minister at last consented to have it transferred to the Imperial Government.

The Squadron, thus strengthened, left Shinagawa on March the 9th, and on the 24th March was at Kuwagasaki, a point not far from Hakodate. Here a fight took place, on April 29. The Shogunal Flagship, Kwaiten, with two other vessels, attempted a surprise attack on the Loyalists which was nearly successful. Most of the Loyalist Captains were ashore at the time when the attack was made, but the fog caused the Shogunal vessels to part company, and the Kwaiten alone arrived at the place of destination. Here she found the Stonewall Jackson, now known as the Musashiy lying at anchor, and expecting nothing less than an attack from the Shogun's forces. The Musashi, was an iron-clad, but that consideration did not prevent the Kwaiten from proceeding to the attack, and she maneuvered so skillfully that presently the two ships were lying alongside of one another, and the rebels, leaping on board the Musashi, tried to capture her by assault. The attempt failed, however, and the Kwaiten had considerable difficulty in extricating herself from the dangerous position into which her daring had placed her.

Meanwhile her two consorts, the Banryu and Takao, which had lost her in the fog, seeing that the attack had failed, did their best to return to Hakodate. In this the Banryu succeeded, but the Takao, pursued by the Kasuga (Togo's ship) ran aground near Omotomura and was fired by her own crew.

The engagement at Kumagasaki did much to restore the balance between the two fleets. The Imperialists had, it is true, lost over 100 men while the Rebel loss was only 17 killed and 34 wounded; but they had lost one of their best ships, the Takao, and as the Kwaiyof which we have already seen in action off Awa, had been lost during a gale, the Shogunal Fleet was now not much stronger than the Loyalist, and had no vessel that could withstand the iron-clad Musashi.

The remnants of Enomoto's Fleet were soon after this completely disposed of. In May 1869 the Imperialist ships were engaged in the task of covering the landing of troops on the shores of Yezo near Esashi, and the rebels, after vainly attempting to defend that town, were at last driven back into Hakodate, which was invested. During these operations, the Shogun's people lost all their smaller ships, so that, by the end of the month, they were reduced to three ships, Kwaiten, Banryu and Chiyoda, all three of which had been more or less damaged in action. On the 14th June, the Chiyoda struck on a rock and was abandoned by her crew. The next morning, she floated off without assistance, and came floating on the tide towards the Imperialist Squadron. The Imperialists, with the memories of Kuwagasaki fresh in their memories commenced firing on her, and it was some time before they discovered that they had been wasting their powder on a deserted vessel.

There remained now only the Kwaiten and the Banryu. In a general attack on Hakodate made on June 20th, these two vessels performed prodigies of valor against tremendous odds. A shot from the Banryu fired the powder-magazine of the Clioyo and destroyed her, and her crew fought valiantly until she at last received her coup de grace in a shell from the Kasuga which smashed her engines and disabled her. The Banryu was now sunk by her own crew, and the Kwaiten,

seeing further resistance to be hopeless, followed her example.

Thus was quenched the last spark of resistance to the Imperial forces in Japan. Enomoto surrendered on the 27th of June and the pacification of the country was complete. It is true that we shall again find rebels in arms against the constituted authorities, but Saigo's rebellion was a different thing altogether. He was not fighting, as was Enomoto, for the maintenance of a political system which had been established for many years.

We can feel and admire the loyalty which prompted these men to hold fast to the Shogunate from which their families had in the past, received so many proofs of kindness and consideration. This feeling was shared by the Imperialist party itself and the generosity with which the Emperor treated the faithful adherents of the lost cause has done much to heal the wounds of the civil strife.

And what are we to say of Togo's share in these events?

We see in him the patient painstaking officer, diligent in the performance of his duty, absolutely devoid of all thoughts of self, and happy in the triumph of his Master's cause.

We can say no more than that. His ship, the Kasuga, did good service in the pursuit of the Takao, and the attack on the Banryu. His own personal interest in the fight is shown by his involuntary exclamation (" the coward ") .when he saw the Teibo retreating from her position to avoid the explosion of the Choyo during the battle at Hakodate. He was for a long time chaffed by his messmates for having "scolded a man-of-war".

There are no picturesque incidents in this part of Togo's life: nothing to strike the imagination of the reader, such as we find in the Life of Nelson. His was the life of the quiet conscientious officer, a life not without its effect on those amongst whom it was lived. Togo had already attracted the attention of his superiors and this is proved by his being presently selected as a promising officer, whom it would be well to send to England for further training.

CHAPTER. V. Togo in England

When the Hakodate fleet under Enomoto had been destroyed the Loyalist troops returned in triumph to Yokohama, and what had now become the capital city of Toky5, and it was at Yokohama that the Kasuga was paid off.

Togo's employment was now for a while at an end. The Satsuma Navy had ceased to exist with the restoration of the Imperial Power, which brought all military and naval forces under the control of the newly-formed central government, and the Imperial Navy had not yet been founded.

Still his heart remained in the naval profession, and the experiences of the Hakodate campaign having been quite long enough to let him know the imperfections of Japanese seamanship, his own included, he made application through the leading men of his clan to be sent to England for purposes of study. He had many rivals to fear, for there was then a desire in every young samurai to visit foreign countries and learn something that might be of use to his country and himself, and the responsible officers were over-run with applicants wishing to be sent abroad. His first applications were unsuccessful, but when his fellow-clansman Okubo, was Minister for Home Affairs, Togo made application once more, and after some delay- found that he had been chosen.

We can well imagine the anxiety with which he awaited the verdict of the authorities. The Japanese say that one evening a band of Satsuma young men and others, whom the generosity of their ex-lords was keeping in Tokyo as students, unable any longer to restrain their eager curiosity, went to a fortune-teller to learn their future destiny. The fortune-teller, anxious to please, prophesied smooth things, and told the first three or four that they were going to be greatly distinguished, so that everything went off pleasantly until No. 5, a student named Matsuyama, presented himself, much the worse for liquor. Matsuyama was not pleased with the fortune he received, and a noisy altercation ensued during which the others, who had not yet been examined, picked up the fees they had already paid, and walked out in disgust. Thus Togo was prevented from hearing about his future victories in the seas around Japan.

However, the permission came at last, and Togo, who had been utilizing the precious moments in learning English at Yokohama, from missionaries and from the soldiers belonging to the Legation guard, received his marching orders in March 1871.

He and his companions must have presented a strange appearance as they left Yokohama for Europe. There were no tailors, then, for Japanese who wished to be dressed as foreigners, and the future Nelson of Japan started in a second-hand costume which must effectually have obliterated all signs of a destined greatness. He must during his voyage have been continually treated with a good- natured contempt due entirely to his clothes, and yet surely no one ever deserved less to be treated with disdain than did he.

Togo was a fine specimen of the Bushido in which he had been trained. We have seen already, in our account of the Gochu or Associations of young men in Satsuma, how the youthful samurai of that province were taught to endure pain and to look fear in the face without flinching. But he learned other virtues as well. The short sword in his girdle was a perpetual reminder to him that death was at all times preferable to dishonor, that the remedy for disgrace was in his own hands. The proverb bushi ni nigon nashi, ("the bushi has no second word") reminded him of the cardinal virtue of truthfulness, consistency, faithfulness to promise. Fair play and loyalty were ingrained in the bushi's character, and the civil war which had just come to an end was an admirable specimen of those chivalrous qualities in action. Each side had treated the upholders of the other side with the utmost respect and consideration. The Satsuma retainer, loyally supporting his feudal lord, was quite ready to accord all honor to the Tokugawa samurai, who was only doing his duty by his lawful master. ~ Both parties were united in their reverence for the Sovereign, and their only thought was how to deliver him from the mistaken council of the men that formed his entourage. The Sovereign, on his part, recognized the good feelings . that animated both parties of his subjects, and when the fortune of war decided that the victory should belong to the Satsuma men, the vanquished were treated with the utmost generosity. The living were pardoned, and admitted to the Imperial presence and councils, the dead were honored with those posthumous rewards of rank and position which mean so much in the Japanese world : even Saig5, who died in arms against his Sovereign, was pardoned posthumously, and restored to his former dignities. The one exception to this universal clemency has been the unfortunate Ii Kamon no Kami, the Shogunal Prime Minister, and he, undeservedly as I believe, lies under the reproach of not having " played the game" in his dealings with his Imperial Master.

Togo's chivalrous spirit was to be shown years after in the first attack upon Port Arthur. Ancient etiquette required that the knight 'should notify his own name and titles to his enemy before commencing a combat with him, and it was absolutely the correct thing for Togo to do when, a few hours before his attack, he sent a wireless message to Admiral Makaroff, advising him to surrender.

How Togo must have rejoiced when he got to know, as he must have done during his time in England, a few of the old-time English gentlemen whose ideals of life and honor were perhaps the nearest approach in modern times to the spirit of the Japanese bushi. In the year 1871, Thackeray had not been very long dead—not more than ten years or so:—Col. Newcome and Major Pendennis were types still recognized as being in existence, and Kinglake's "Crimea", with its justification of a noble though much-abused English samurai, was still making its vigorous appeal to the English sense of justice. Togo must have been just ripe to appreciate the good side of English life and character.

In London, he met several of his compatriots, Satsuma and Choshu clansmen, such as Kawase, Kawakita, and others who were studying like himself. Kikuchi Dairoku, now a Baron, and for some time a Minister of Education, was then either in London, or in Cambridge, and a few others from other parts of Japan were there to form a body round which all the Japanese students in England might from time to time rally. Togo did not want for companions in London, but circumstances eventually led him to Plymouth, to the training-ship " Worcester," which seemed to offer him the greatest facilities for obtaining a practical mastery of the details of his profession. The reports sent home about him were so good that in 1872 the Government decided to grant him the rank and treatment of a 2nd Lieutenant in the Imperial Navy, which had been reconstructed since his departure for England, and when his course of training on board the Worcester was finished, in 1876, he was ordered to remain in England to watch the construction of the new Japanese ship Hiyei, which was finished in January 1878, and reached Japan in the following May.

The Strand magazine for April 1905 contains an article on Admiral Togo " as a youth" in England, written by the Rev. A.S. Capel M.A. to whose care Togo was for some time committed. The writer of this book knew Mr. Capel very well by sight in Cambridge and must have been in residence as an undergraduate of Peterhouse just about the same time, ,though he never saw Togo, nor even heard of his existence.

Mr. Capel tells us that Togo was put under his care for a few months in Cambridge during the interval between his arrival in England and his joining the Worcester training ship.

He knew very little English, and his progress, partly from illness, and partly perhaps from a natural incapacity for mere language study, was very slow. In mathematics however he made much progress, and soon learned enough English to discuss the problems of that science.

Mr. Capel next speaks of his excellent manners, and tells us how it became his practice' to recommend to his other pupils the study of Eastern manners as being so much better than the Western manners which Togo and his brother-Japanese had come to England to learn.

His natural modesty is shown indirectly. When Togo was a student in Mr. Capel's house he was already the hero of two or three naval fights, and what would have delighted the children of the house more than an account of the stirring incidents of the bombardment of Kagoshima? Yet, fond though he was of gossiping with children, he seems to have resisted all temptation to boasting, and Mr. Capel writes as though he did not know that Togo had already gone through a couple of campaigns.

Togo's kindness to animals and fondness for children are early traits which are still to be found in the grown man, only with more scope for their exercise, and we are also told of the wonderful power of enduring physical pain which he showed under the operations made necessary by a long and troublesome affection of his eye. It was this affection which caused Mr. Capel to have the lad removed from Cambridge to Portsmouth, and thence to Plymouth where he joined the Worcester for special nautical training, and yet from the very beginning he had stated his intention of becoming a " sailor on dry land ", by which he was supposed to mean a shore appointment at the Japanese Admiralty.

Mr. Capel incidentally also mentions the young man's fondness for attending Church, the singing of the psalms and hymns having a fascination for him, and the use of the English Prayer-book enabling him to follow with a certain amount of intelligence the worship that was going on. I remember to have read some months ago in a New York paper (I am almost sure that it was the Freeman s Journal) a statement that the Admiral had, during his stay in England, been baptized a Roman Catholic. I have never been able to verify the statement, and I do not think that it is true. The editor of that sheet published this statement when the " yellow peril " folly was at its height, and it was evidently a great comfort to him to think that, if the navies of Christian Russia were doomed to fall before the pagan Japanese, at least the hand that directed the blow was that of a Catholic Christian. It was not much of a comfort, and the little there was in it rested, I fear, on no solid basis of fact. And yet no one can have read the dispatches in which he announced his victories to his Sovereign without being impressed with their deeply religious tone. All wise men, says Lord Beaconsfield, in one of his novels, are religious: all wise men belong to the same religion, but they never say what their religion is.

Whilst Togo was thus laying the foundation of his future greatness in England, great events were happening in Japan. The elder Saigo, the beau- ideal of a Japanese samurai, and the darling of the Satsuma clan, had put himself at the head of a rebellion, which, though nominally directed against the counselors who surrounded the Sovereign, and not against the Sovereign himself, would nevertheless, had it been successful, have ended in the undoing of the whole work of the restoration.

It was due mainly to the Satsuma men that the Emperor had got back to his own. They, with their colleagues of Choshu, Hizen, and Tosa, had overthrown the Shogunate and restored the personal rule of the Sovereign. The statesmen who directed that movement saw that the personal rule of the Sovereign was incompatible with the existence of the quasi-independent princedoms which, during the Feudal times, had covered the whole land. Japan, they insisted, must be unified, and in order that the unification might be accomplished, the minor principalities must go, and a strong central government be established. The great barons, to their endless honor, consented to be “mediatized” and to become the nobility of an united Empire instead of the ruling Princes of a divided land.

But further measures were necessary. If Japan was to become a great nation in the modern sense of the term, it was necessary that she should have a strong army, resting not on the loyalty of the military clans but on the patriotic service of the whole people, and it was also of the utmost importance that she should have a period of peace during which to effect the necessary changes.

It was proposed therefore to abolish the special privileges of the samurai class by adopting universal conscription, and to take conciliatory measures in the matter of certain difficulties which had occurred in Korea.

We, looking back, with the experience of forty years behind us, now know how wise these measures were. Conscription has made samurai of the whole nation, and the present year has seen the sons of farmers and merchants rivaling the deeds of the ancient bushi. The breathing space that Japan needed for her reconstruction has been used to the full, and no fear of foreign aggression disturbs the nation.

But in 1875 or 1876 these results were not so evident. Men of a less penetrating gaze only saw that the samurai class, the backbone of the nation's military power, was being threatened with extinction, at the very moment, too, when foreign Powers were knocking more loudly than ever at the gates of Japan. It was not unnatural that the Japanese samurai, especially those of Satsuma, whose merits had been so great in the troubles which Japan had just passed through, should lift a cry of alarm. Neither was it altogether strange that the rumor of a plot against Saigo's life should send the military students of Kagoshima to arms and at last force Saigo himself to put himself at their head. It was a most regrettable occurrence, but a natural one, and one which the Japanese have done well to condone. Certainly no act could have demonstrated more clearly the magnanimous generosity of the Ruler than that which restored Saigo posthumously to his former honours and allowed his monument to speak to his fellow- countrymen of a life which, if at times a mistaken one, was always noble.

Had Togo been in Japan, he would in all probability have 'gone out' with Saigo. Saigo was a Kagoshima man, a former member of the same gochu to which Togo afterwards belonged. As an older man, and of leading influence in the councils both of the clan and the nation, he had many opportunities of helping his younger clansmen. His influence had frequently been exercised on behalf of members of the Togo family, and when the Kagoshima men rose and placed Saigo at their head in their rebellion, Togo's three brothers all thought it their duty to support him. The three brothers lost their lives in the rebellion: Lieutenant Togo, living peaceably in England, was saved from the necessity of making a difficult decision, and was thus spared to render invaluable service to his country in the hour of her need.

Admiral Togo’s family and his relatives in the garden of the Admiral’s house

CHAPTER VI. Quiet Progress

Lieutenant Togo returned to Japan on board the Hiei, on May 2, 1878, and on the 3d of July following was promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant (chu-i). On the 18th of August, he was transferred to the Fuso, and on the 18th December received another step, being promoted a full Lieutenant (tai-i). The rapidity of his promotion may be taken as some indication of the esteem in which he was held by his superiors.

In May 1879, just one year after his return to Japan, he was moved back to the Hiyei, and in 'December of the same year received the rank of Lieutenant-Commander. In 1880 (January) ht went to the Jingei as Vice-Captain, and received the j unior 6th grade of Court rank, and in December 1881 became Vice-Captain of the Amagi.

Whilst on board the Amagi, he had occasion to see a little service in Korea. On July 25, 1882, he was at Bakwan (Shimonoseki) with his ship when a disturbance broke out at Seoul which summoned him to Korea. A disturbance had broken out in the Korean Capital, and a mob invading the Royal Palace had threatened the life of the Queen. That unfortunate lady (she was murdered some years later) had taken refuge in the Japanese Legation, but the mob had pursued her with violence, and, in the attack on the Legation which ensued, seven Japanese were killed. Mr. (now Baron) Hanabusa, who was at that time Minister, at length managed, with some of his subordinates, to escape on board a foreign ship at Chemulpo, which took him to Nagasaki, where he was able to inform his government of what had occurred.

The Amagi was at once ordered to Korea, and a landing party, of whom Togo was one, marched up to the capital, and, with the good offices of the foreign Powers, succeeded in convincing the Korean King of the wrong he had done in permitting a foreign Legation to be attacked.

The Amagi then returned to Bakwan, and Togo, whose services were recognized by a present from the Government, remained with her until the 24th of February 1883, when he was ordered to come up to Tokyo on board the Nisshin. Arriving at the Capital, he found that he had been appointed Commander of the Teibo, a ship which he did not long retain, as, in May 1884, he was sent back

to the Amagi, as commander, and ordered to cruise along the Chinese and Korean coasts to observe the operations of the Franco-Chinese war which was then in progress. It was recognized that he, especially, was the man to whom such an opportunity would be profitable. At the conclusion of that war, he returned to Tokyo, when he made a special report in person to His Majesty, and was honored by a banquet. The significance of this is very clear. The quiet, patient, and yet determined officer was making his way up in the ranks of his service.

From June 1885 to May 1886, he had shore billets, partly at the Shipping Bureau of the Naval Department in Tokyo (Shusenkyoku) and partly at the Onohama Dockyard. He was then placed as commander on board the Yamato, but transferred in November to the Asama, a post which held for some time concurrently with the Superintendency of the Yokosuka Arsenal [Heiki Bu Cho). In July 1887 he was at Yokosuka as President of the Court Martial which tried the case of the stranding of the Kongo. In 1889 we find him appointed to the Hiyei, promoted full captain, and advanced in Court rank. In 1890 he was for a short time Chief of Staff at the Kure Naval Station. In 1891 he was appointed to the Naniwa, the armored cruiser, which was destined to bring his name" for the first time before the world outside the naval circles of Japan. In this ship he cruised around the coasts of China and Korea (1892), visited the Hawaiian archipelago to care for Japanese interests (1893), and cruised off Hokkaido and Vladivostok (1894). In that year he had a break for two months on shore as Director of the Kure Naval Station, but in June he was back again on the Naniwa, and in Chinese waters, waiting for his opportunities of service in the imminent war with China.

None but a Japanese, or one of those favored foreigners who have been privileged to see the Japanese Navy from within for a long course of years, can form an idea of the strenuous character of the period which we have been considering in this chapter.

Togo's life, with its continuous changes, and its rapid succession of duties and responsibilities was no more strenuous than that of any of the hundreds of able and ambitious officers who were at this time engaged in the creation of the Japanese Navy as a first-class fighting force.

The material they had to work with was in truth of the very best, nevertheless, the task was a Herculean one. The authorities had to turn them hardy and daring fisher population of the sea-board of Japan into an effective force of blue-jackets, capable of understanding and handling the complex machinery of a modern battle-ship, and worthy of a place side by side with the jack-tars of Britain, America or Germany. In order to do this, a body of able officers was absolutely needed, and though the samurai were ready at hand with traditions of military valour, the samurai themselves needed to be shown how much more than mere valour was necessary for the evolution of a naval officer. The samurai, especially in the days of confusion and laxity which preceded the fall of the Shogunate, had fallen into lawless ways and needed to feel the force of a strict discipline. Instructors could be procured, but education was not so easy. There was a temptation to political activity in days when young Japan was looking forward with feverish anxiety to the gift of constitutional government, which was to give to every intelligent student a chance of political distinction, and it was rather hard for the samurai, whose influence had been so great during the birth-throes of the Restoration, to turn a deaf ear to the allurements of party politics. There was also another danger. Intercourse with foreign nations had revealed to the Japanese the immense wealth of England and America, and the gospel of materialism had come in, along with other gospels, to break down the old ideals of mediaeval Japan. It was absolutely necessary to keep the Japanese naval officers free from the materialistic notions of the West, and to make them feel so inspired with the dignity of their noble profession that they should value the comparative poverty which their uniform implied above the more tangible comforts of wealth and ease. There was yet another task. Satsuma men had been the creators of the Navy, and their influence has always been very great in the force. But men of other clans were now chosen to fight side by side with these intrepid and hot-headed men from the South. It wanted an infinity of tact, patience, perseverance and good sense to eradicate the clan feeling from the force, to merge all local interests in the higher interests of the Empire, and to make all, officers and men alike, feel that none of them would be left out in the cold, but that, provided a man were a good officer, it did not much matter where he hailed from. The success which attended these efforts was largely due to the patient, self-denying efforts, of that band of devoted officers whom Togd so well represents, and when we think of the glories of the Japanese .Navy in the twentieth century we must not forget the patient labors of the latter part of the nineteenth.

Japan is, and perhaps always will be, a comparatively poor country, and her poverty hindered her naval expansion for years. It costs much money to buy and equip vessels of war, and Japanese Parliaments in the early days were not always eager to vote supplies for a fleet, the utility of which was not then as clear to the man in the street as it is now. The authorities were consequently obliged to go slowly in the work of organization. It was doubtless irritating to have to do so, but it was good that it was so. The smaller ships were as much as the inexperienced crews of those early days were competent to manage effectively, and by reason of this very tardiness of development the Japanese Navy was probably saved from many of the disasters which other navies have met with even in days of peace. When Togo was appointed Captain of the Naniwa, that vessel was one of the finest ships of the Japanese Navy. Launched at Elswick in 1885 and completed the following year, she is 300 ft in length, with 36 ft of beam, and a draught of 18.5 ft. Her displacement is 3700 tons, her indicated horsepower, 7235. , Her deck armour is 3 in. for gun positions. She carries 2 ten-inch and 6 six-inch guns, steams 18.72 knots with a coal capacity of 800 tons, and has a complement of 350 men. If we compare these dimensions with those of the monster battleships which now fly the Flag of the Empire, they are as nothing. But in 1893 they meant a great deal.

CHAPTER VII. The War with China

Korea had for a long series of years afforded a bone for contention between China and Japan. The friendly overtures, made by the Imperial Government to Korea in 1868, had been rejected by the Government of that country, which inclined strongly towards the stagnant decay of the Celestial Empire, from whose rulers it received constant encouragement, a Japanese man-of-war was even fired upon by the Koreans in the early days of Meiji, and we have already had occasion to refer to the attack made by the anti-reform and anti- foreign parties in the Korean Capital on the Japanese Legation at Seoul, and Mr. Hanabusa's narrow escape from imminent peril.

Two years later another peril threatened the peace. The Korean reformers under Kim-Ok- Kyun formed a conspiracy to murder their political rivals of the conservative, or Chinese, party during a banquet, to get possession of the Person of the King and, to establish a progressive Government. In this attempt they seem to have confidently, though without official authority, reckoned on Japanese support; for Japan, they thought, would naturally be well disposed towards any attempt at progress or enlightenment; thus, when their plot had been, in part at least, successfully carried out, they appealed to the Japanese Legation Guard to protect the Royal Palace and Person. This brought the Japanese into collision with the Chinese troops, who were called in to aid by the anti-reform party, and, a regular fight ensuing, the Japanese and reformers were driven out of the Royal Palace, the Japanese Legation was again attacked and burnt, and the Legation staff and escort obliged to take refuge at Chemulpo.

The Diplomacy of the foreign Powers now intervened to save the situation. Korea apologized to Japan, and agreed to pay an indemnity for the destruction of the Japanese Legation, and both Japan and China promised by the Treaty of Tientsin, in April 1885, to withdraw their troops from Seoul. A second portion of the same treaty provided that if at any future time the interests of one party required, or seemed to require, the presence of its troops in Seoul, the other party should be notified of the fact, and be entitled to send an equal force for the protection of its own interests.

The Treaty of Tientsin worked fairly well for several years. The Governments of the three countries were outwardly at peace, and the surface of affairs was smooth; but there was much unofficial intriguing going on, and it was just as impossible for the Korean Reform party not to look to Japan for sympathy as it was for the Conservatives to refrain from covert appeals to Chinese fellow-feeling. The methods resorted to by both parties were reprehensible at times, but we must remember that misgovernment always leads to deeds of violence, and the misgovernment in Korea had been long a bye-word and reproach.

The Korean reformer Kim-Ok-Kyun had been obliged to leave his country after the events of 1884. He spent the years of his exile mostly in Japan, in retirement and semi-concealment; but in March 1894 he was at Shanghai, staying in a boarding-house under an assumed name, and was there assassinated by a Korean named Hung. The Chinese authorities arrested Hung, but, instead of punishing him themselves, sent him along with the body of his victim to Seoul. At Seoul, however, he received no punishment: he was on the contrary loaded with honors by the Korean King, whilst Kim-Ok-Kyun's body was quartered and exposed to view in public places in the city.

Everything looked as though the murder of Kim-Ok-Kyun had been done by the order of the Korean Government with the approbation of China, and the indignation of the Japanese, who looked upon Kim-Ok-Kyun as being under their protection, knew no bounds.

The Conservatives in Korea now felt themselves in a position to take more decided steps of a reactionary nature, and for this purpose allowed the Tonghaks in the south of the peninsula a somewhat free hand. The Tonghaks, originally a religious organization, had developed strong political tendencies of an anti-foreign nature. In the spring of 1894, they rose in arms and proclaimed a policy of expulsion which was directed mainly against the Japanese, as being practically the only foreign nationality largely represented in the Peninsula.

The Korean Government, professing not to find itself in a position to quell this insurrection, applied to China for help. On the 7th of June 1894, the Chinese Minister in Tokyo informed the Japanese Government, in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty of Tientsin, that China intended sending troops to Korea " for the sake of helping a tributary state" in the hour of need. Japan refused to recognize the definition of Korea's tributary status, and prepared to provide for her own interests. Negotiations were at once commenced, with a view to providing a smooth way out of the difficulties: the Japanese Government came forward with reasonable propositions, which, if adopted, might have brought prosperity and contentment to the much-distracted Hermit Kingdom, and at the same time made it clear that she would not offer advice without being prepared to back it with something more substantial. By the end of June, there were in and around Seoul some six or seven thousand Japanese troops whose presence effectively caused a collapse of the Tonghak rebellion. The Chinese had a squadron in Korean waters, as had also the Japanese, and a force at Asan; but the force remained stationary and inactive, and its commander contented himself with exhortations to the Tonghaks to return to obedience, and pompous proclamations about the solicitude of China for the welfare of a tributary state.

On previous occasions, diplomacy had always found a way out of the oft.-recurring difficulties between Japan and her neighbors, and this time also efforts at mediation were not lacking. But Japan was determined not to be trifled with. Korea was a buffer state between herself and a Power which her statesmen had long had reason to dread. Korea, well governed, might be a real protection : Korea, governed according to Chinese notions corrupted to suit Korean tastes, could only fall into, hostile hands. The hour had come for Japan to. secure for good her ascendancy in Korea, by showing how weak a reed China was to lean upon — diplomatic attempts failed, and Japan sent her ultimatum on July 19th 1894.

On the 23d of July, Admiral Ito, acting under orders from the General Quarters, left Sasebo with the main portion of his Fleet, the Flying Squadron under Rear-Admiral Tsuboi, consisting of the Yoshino, Akitsushima, and Naniwa, being sent ahead to reconnoitre. These vessels, early on the 25th, fell in with the small Chinese cruiser Tsi-yuen, and the gun-boat Kuang-yi, with which they had a fight, the end of which was that the gun-boat was run ashore in a sinking condition whilst the Tsi- yuen, escaped only by pretending to surrender, and making off later whilst the attention of the Japanese was engaged elsewhere. The Japanese had been drawn off in pursuit of the Chinese despatch-boat Tsao-kiang, (which was captured without resistance), and the British steamer Kaosheng, under charter to the Chinese Government as a transport, which was sunk by the Naniwa, for refusing to obey orders.

Togo's action in sinking the Kaosheng, was severely criticized the whole world over as a piece of high-handed violence. It is therefore advisable to reproduce here the guarded and moderate statement of the occurrence given by the Japanese Imperial General Staff in their History of the War with China. It will show how correct was Togo's interpretation of his duties under very difficult and trying circumstances, and it is a pleasure to think that, when all the circumstances of the case came to be known, his conduct met with the general approval.

[About 10.30 a.m. the Naniwa steamed up to a transport which had been compelled to anchor at Shopaioul Island, and sent Zengoro Hitomi, Lieutenant of Marine, with Nenjitsu Waraya, 3rd class Engineer, to examine her. This officer made enquiries of her Captain, Thomas Ryder Galdsworthy, and examined the ship's books and papers, from which he learned that the ship was named the Kao-sheng, that she flew the British flag, was owned by the Indo-China Steam Navigation Company, and had been chartered for this trip by the Chinese Government. She had taken on board troops, arms, and ammunition at Taku and was conveying them across to Asan. The Lieutenant thereupon ordered the Kao-sheng to follow the Naniwa, which the Captain after some hesitation consented to do. Lieut. Hitomi then returned to his ship.

The Naniwa next signaled to the Kao-sheng to weigh anchor, but her Captain signaled in reply that he wished to confer upon some important matters, and asked for a boat to be sent, whereupon Lieutenant Hitomi again went on board the transport. During the first interview the master of the Kao-sheng had admitted to that officer that he was not in a position to disobey the orders of the Naniwa, and that he was quite willing to carry out the Naniwa’s orders, but that the Chinese officers on board refused to allow him to do so. He had then asked them to be allowed to land with his own crew, but the Chinese had threatened that, if he attempted to leave the ship or to carry out the orders of the Naniwa, they would kill every European on board. They had also put soldiers armed to watch over the master and mates, and to prevent the engineers from entering the engine room, and when the boat was on its way the second time from the Naniwa they tried to prevent the captain from communicating with it. When Lieutenant Hitomi came on board again, the Captain told him that the Chinese officers would not allow him to obey the orders of the Naniwa, and that they asked to return to Taku on the ground that they had not received notice before starting of the declaration of war. Lieutenant Hitomi felt that this was a very serious matter, as the ship was full of arms and war-material, and returned to his ship to report it.

It was the hearty desire of the Captain of the Naniwa to save the Kao-sheng and the lives of the Chinese troops on board, and several communications passed to and fro between the ships, but the Chinese soldiery only became more violent in their behaviour to the Captain, and at last the Naniwa signaled to the Kao-sheng's crew to leave her at once. This the Chinese general would not permit, and so they asked the Naniwa to send a boat to fetch them away. This request could not be granted, for matters were now very critical, and it was quite uncertain what course the Chinese troops might take it into their heads to adopt, so the captain of the Naniwa signaled to the Kao sheng’s crew to come in their own boat, a course which the Chinese again refused to allow them to follow.

The Captain of the Naniwa now recognized that the Captain was helpless against the menaces of his Chinese passengers, so he ordered the crew to leave the ship, hoisted a red flag at the masthead, and whistled several times as a sign of imminent danger: whereupon the captain and crew of the Kao-sheng jumped overboard one after the other.