Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

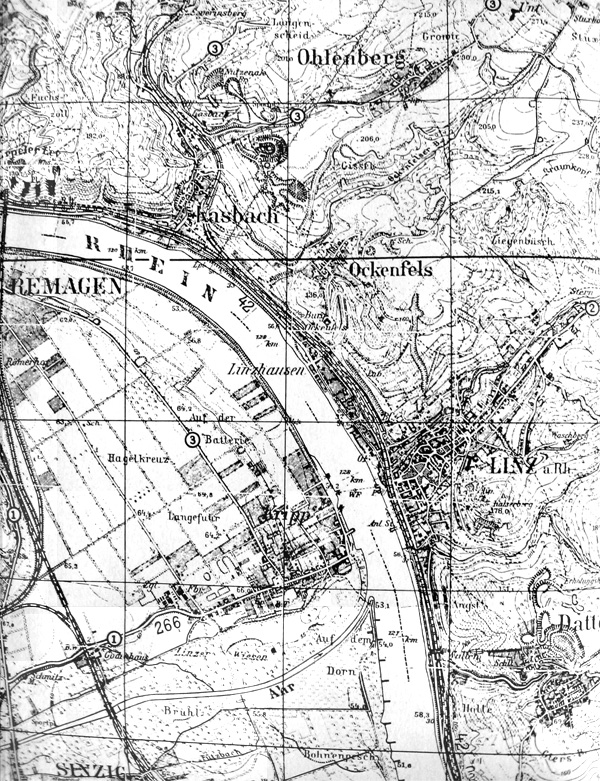

THE REMAGEN BRIDGEHEAD, MARCH 7-17, 1945

Remagen Bridgehead. Photographed March 27, 1948 for the Historical Division SS USA by the 45th Reconnaissance Squadron under the supervision of Major J.C.Hatlem

PREPARED BY RESEARCH AND EVALUATION DIVISION

The Armored School

PREFACE

The purpose of this study is to collect all available facts pertinent to the Remagen Bridgehead Operation, to collate these data in cases of conflicting reports, and to present the processed material in such a form that it may be efficiently utilized by an instructor in preparing a period of instruction. The data on which this study is based was obtained from interviews with personnel who took part in the operation and from after action reports listed in the bibliography. This is an Armored School publication and is not the official Department of the Army history of the Remagen Operation. It must be remembered that the Remagen Operation is an example of a rapid and successful exploitation of an unexpected fortune of war. As such, the inevitable confusion of facts and the normal fog of war are more prevalent than usual. The absence of specific, detailed prior plans, the frequent changes of command, and the initial lack of an integrated force all make the details of the operation most difficult to evaluate and the motives of some decisions rather obscure. The operation started as a two-battalion action and grew into a four-division operation within a week. Units were initially employed in the bridgehead, as they became available, where they were most needed: a line of action that frequently broke up regiments. In cases of conflicting accounts of the action, the authors of this study have checked each action and each time of action included in the study and have evaluated the various reports in order to arrive at the most probable conclusions.

FOREWORD

The following comments are included in this study of the operation for the benefit of those who will follow and who may be confronted with the responsibility of making immediate, on-the-spot decisions that are far-reaching in their effect and that involve higher echelons of command.

The details of the operation are valuable and should be studied, as many worthwhile lessons can be learned from them. In this study, which should be critical, the student should approach them by "Working himself into the situation;" that is, by getting a clear mental picture of the situation as it existed at the time it took place.

First and foremost, the operation is an outstanding proof that the American principles of warfare, with emphasis on initiative, resourcefulness, aggressiveness, and willingness to assume great risks for great results, are sound. The commander must base his willingness to assume those great risks upon his confidence in his troops.

Commanders of every echelon from the squad up who take unnecessary risks that are rash, ill-conceived, and foolhardy should be removed from command.

Hence the need and value of good training.

In this particular operation the entire chain of command from the individual soldier, squad, platoon, and on up through the highest echelon, SHAEF, saw the opportunity and unhesitatingly drove through to its successful execution.

It is impossible to overemphasize this as an illustration of the American tradition and training.

Military history is replete with incidents where wonderful opportunities were not grasped, with resultant failure.

The fact stands out that positive, energetic actions were pursued to get across. The traffic jams, the weather, the road nets, the change in plans, did not deter anyone from the primary job of getting across the Rhine and exploiting this wonderful opportunity.

The results are history.

One other thought. When a reporter asked Sergeant Drabick, the first soldier across the bridge, "Was the seizing of the bridge planned?" "I don't know about that, all I know is that we took it," was his reply.

This sums it up in a nutshell. So much for the operation.

It might be well for future value to surmise what would have happened if the operation had failed. Assume for this purpose that 24 or 36 hours after the initial troops crossed, the bridge had gone down from delayed time bombs or from air bombing or the direct artillery fire, which was extremely accurate the first few days. It actually did collapse on 17 March.

Those troops already across would have been lost.

Would the commanders who made the decisions have been severely criticized?

My purpose in this question is to create discussion. My hope is that your thinking will result in the answer that they would not.

Commanders must have confidence not only in those under their command but also m those under whom they serve.

In this specific case we had this confidence.

JOHN W. LEONARD

Major General, USA

Formerly Commander, 9th Armd Div

INTRODUCTION: SEIZURE OF THE LUDENDORF BRIDGE

Remagen bridge

At 071256 March 1945, a task force of the United States 9th Armored Division broke out of the woods onto the bluffs overlooking the RHINE RIVER at REMAGEN (F645200)[*], and saw the LUDENDORF BRIDGE standing intact over the RHINE. Lieutenant Colonel Leonard E. Engeman, the task force commander, had under his command: one platoon of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, the 14th Tank Battalion (Companies B and C), the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, and one platoon of Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion.[1] Beyond the river lay the heartland of Germany, and presumably the organized defenses of the RHINE. Lieutenant Colonel Engeman's original orders were to capture REMAGEN (F645200) and KRIPP (F670180). However, in a meeting between the Commanding Generals, 9th Armored Division and Combat Command B of that division, it had been decided that if the LUDENDORF BRIDGE at REMAGEN were passable, Combat Command B would "grab it." This information had been sent to Lieutenant Colonel Engeman.[2]

About 062.300 March the III Corps commander, Major General Milliken, had remarked to Major General Leonard over the phone, "You see that black line on the map. If you can seize that your name will go down in history," or words to that effect. This referred to the bridge.

The plan of assault as formulated by the column commander and as subsequently executed was an attack on REMAGEN (F6420) by one company of dismounted infantry and one platoon of tanks followed by the remainder of the force in route column and supported by assault guns and mortars from the vicinity of (F633204).[3] This plan obviated the necessity of moving any vehicles within the column prior to the time of attack. The plan further provided that the assault tank platoon should move out 30 minutes after the infantry, with the two forces joining at the east edge of town and executing a coordinated attack for the capture of the bridge.[3]

[*]For all map references in tis study see Maps. appendix V.

[1]Statement of Lt. Col. Engeman, CO, 14th Tank Battalion.

[2]After Action Report, 14th Tank battalion. march 1945, page 8.

[3]After Action Report, 14thTank Battalion, March 1945, page 12.

As enemy troops and vehicles were still moving east across the bridge at the time (1256), the column commander requested time fire on the bridge with the dual purpose of inflicting casualties and of preventing destruction of the structure. This request was refused due to the difficulty of coordinating the infantry and artillery during the assault on the town.[1]

Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, moved out at 1350 following the trail which runs from (F629204) to (F635204). At 1420, the 90-mm platoon of Company A, 14th Tank Battalion, left the woods at (F632204) and started down the steep, twisting, tree-lined road that enters REMAGEN at (F639201).[2] The tank platoon arrived at the edge of town before the infantry and, meeting no resistance, continued on into the town. The infantry, upon arriving at the edge of town, was able to see the tanks already moving toward the bridge, so it followed along the main road running southwest through the center of REMAGEN.1 The town appeared deserted— the only resistance encountered was a small amount of small-arms fire from within the town2 and sporadic fire from 20-mm flak guns which enfiladed the cross streets from positions along the east bank of the river.[3] The tank platoon reached the west end of the bridge at 15002 followed shortly by the company of infantry. By 1512, the tanks were in position at the western end of the bridge and were covering the bridge with fire. At the same time, a charge went off on the causeway near the west end of the bridge, followed shortly by another charge two thirds of the way across. The first charge blew a large hole in the dirt causeway which ran from the road up to the bridge; the second damaged a main member of the bridge and blew a 30-foot hole in the bridge structure. A hole in the bridge floor which the Germans were repairing made the bridge temporarily impassable for vehicles.[4] The assault guns and mortars began firing white phosphorus on the town of ERPEL (F647205) at this time (1515) in an attempt to build up a smoke screen over the bridge. A strong, upstream wind prevented complete success, but partial concealment of the assaulting force was accomplished.[5] The use of burning white phosphorus demoralized the defenders and drove them to cover. The remainder of Company A, 14th Tank Battalion, arrived at the bridge and went into firing position downstream from the bridge. The 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, less Company A, dismounted in the town and prepared to assault the bridge.[1]

At 1520, a captured German soldier reported that the bridge was to be blown at 1600 that day. This information, which appears to have been widely known, was substantiated by several citizens of REMAGEN (F6420).

In order to evaluate properly the initial decision to establish a bridgehead over the RHINE and the subsequent decisions of higher commanders to exploit the operation, it is necessary to understand the plan of operation at the time. The mission of the 9th Armored Division was to go east to the RHINE and then cut south and establish bridgeheads over the AHR RIVER preparatory to continuing south for a linkup with the Third Army. Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, was on the north and east flank of the division, charged with accomplishing the division mission within the zone of the combat command. The task force commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Engeman was, of course, one of the striking forces of the combat command. No specific orders had been issued to anyone to seize a RHINE bridge and attack to the east. The decision to cross the bridge and to build up the bridgehead required a command decision at each echelon—a decision which was not as obvious as it appears at first glance.

[I]Statement of Lt Col Engeman, CO, 14th Tank Battalion.

[2]After Action Report, 14th Tank Battalion, March 1945, page 12.

[3]Statement of Maj Cecil E. Roberts, S-3, 14th Tank Battalion.

[4]Statement of Lt John Grimball, 1st Platoon, Company A, 14th Tank Battalion.

[5]After Action Report, 14th Tank Battalion, March 1945, page 13.

It is probable that very few places along the whole stretch of the RHINE were less suited for a large-scale river crossing. From a tactical standpoint, the REMAGEN BRIDGE was on the north shoulder of a shallow salient into the enemy side of the river. The ground on the east bank rose precipitously from the river and continued rising through rough wooded hills for 5000 meters inland. The primary road net consisted of a river road and two mountain roads, any of which could be easily blocked. From a supply and reinforcement viewpoint, the bridge site was near the southern, army boundary. Only one primary road ran into REMAGEN from the west, and that road did not run along the normal axis of supply. Furthermore, there had been no build-up of supplies at the crossing site in anticipation of a crossing at that point. As previously stated, therefore, the decision was not so obvious as it first appears. The possibility of putting a force across the river only to have the bridge fall and the force annihilated approached the probable. A negative decision which would have ignored the possibility of seizing the bridge while insuring the accomplishment of the assigned mission would have been easy. Probably the most important observation noted on the whole operation is that each echelon of command did something positive, thereby demonstrating not only a high degree of initiative but also the flexibility of mind in commanders toward which all armies strive but which they too rarely attain.

At 1550, Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, reached the east bank of the river, closely followed by Companies B and C.[1][2] The crossings were made under sporadic fire from 20-mm flak guns and uncoordinated small-arms fire from both sides of the river.[2] The guns of Company A, 14th Tank Battalion, drove the German defenders from the bridge road surface and from the stone piers of the bridge. In addition, the tanks engaged the flak guns on the east bank which were opposing the crossing.[3] On gaining the far shore, Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, turned downstream and began sweeping ERPEL (F647207). Company B scaled the cliffs immediately north of the bridge and seized HILL 191 (F645208) while Company C attacked toward ORSBERG (F652216).[4] Troops from Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion, moved onto the bridge with the assault infantry. These engineers, moving rapidly across the bridge, cut every wire in sight and threw the explosives into the river.4 No effective repairs of the bridge could be accomplished until dark, however, due to extremely accurate and heavy fire from the snipers stationed on both banks of the river.[5]

As the leading elements reached the far shore, CCB received an order by radio that missions to the east were to be abandoned: "Proceed south along the west bank of the RHINE." At 1615 the Commanding General, Combat Command B, received an order issued to his liaison officer by the division G-3 at 071050 March, ordering Combat Command B to "seize or, if necessary, construct at least one bridge over the AHR RIVER in the Combat Command B zone and continue to advance approximately five kilometers south of the AHR; halt there and wait for further orders." Upon receiving this order, General Hoge decided to continue exploitation of the bridgehead until he could confer with the Commanding General, 9th Armored Division. By 071650 March, the division and Combat Command B commanders had conferred at BIRRESDORF (F580217), and the division

[1]After Action Report, 14th Tank Battalion, March 1945, page 13.

[2]After Action Report, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, March 1945, page 6.

[3]Statement of Lt John Grimball, 1st Platoon, Company A, 14th Tank Battalion.

[4]Alter Action Report, CCB, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, page 9.

[5]Statement of Maj Cecil E. Roberts, S-3, 14th Tank Battalion.

commander directed Combat Command B to secure and expand the bridgehead.[1] Task Force Prince at SINZIG to be relieved by Combat Command A and Task Force Robinson on the north to be covered by one troop, 89th Reconnaissance Squadron; division responsible to the west end of the bridge.[2] This released for the bridgehead forces the following units:

Company C, 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Troop C, 89th Reconnaissance Squadron.

52d Armored Infantry Battalion.

1st Battalion, 310th Infantry.

1 platoon, Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion.

Provisions were made to guide these units to their areas, and a time schedule of crossing was drawn up.[3]

The command post of the bridgehead force was set up in REMAGEN 200 yards west of the bridge at 1605. Combat Command B command post was established at BIRRESDORF (F580217) at 1200.

At 1855, the bridgehead commander received orders from Combat Command B to secure the high ground around the bridgehead and to mine securely all roads leading into the bridgehead from the east. In addition, he was informed that the necessary troops required to perform this mission were on the way and that the division would protect the rear of the task force.[4]

A dismounted platoon from Company D, 14th Tank Battalion, swept the area between the railroad and the woods on the high ground west and south of REMAGEN. This job, which was completed at 2040, silenced the flak guns and drove out the snipers who had been harassing the engineers working on the bridge.[3]

Late in the evening American Air intercepted a German order directing a heavy bombing attack on the bridge to be made at 080100 March. However, the bad weather prevented the German planes from getting off the ground.[2]

During the night, the two roads leading into REMAGEN from BIRRESDORF on the west and SINZIG (657164) on the south, as well as the streets of the town, became clogged with traffic; first by units of the combat command being hurriedly assembled, and later by reinforcements being rushed up by III Corps. The night was rainy and very dark, which necessitated great efforts from all concerned to keep traffic moving at all. The bridge repairs, completed by midnight, permitted one way vehicular, traffic. Company A of the 14th Tank Battalion, less its 90-mm platoon, crossed successfully; and Company C, 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion, followed. The leading tank destroyer slipped off the temporary runway on the bridge in the darkness and became wedged between two cross members of the structure, thereby halting all vehicular traffic for a period of three hours. By 080530 March, when the tank destroyer was finally towed off the bridge, the traffic jam was impeding movement as far back as BIRRESDORF (580217).[5]

During the next 24 hours, the following-designated units crossed the bridge:

080015 March

Company A, 14th Tank Battalion, less one platoon, crossed and set up a road block at (F642211) and one at (F656203).

[1]After Action Report, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, pages 19, 20.

[2]Statement of Major General Leonard.

[3]After Action Report, 14th Tank Battalion, March 1945, page 14.

[4]After Action Report, 14th Tank Battalion, March 1945, page 13.

[5]After Action Report, CCB, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, page 10.

080200 March

52d Armored Infantry Battalion, dismounted, started across the bridge. The battalion established its command post at ERPEL (F647207) at 0630 and took over the north half of the perimeter from UNKEL (F634224) to (F652227).[1]

080700 March

1st Battalion, 310th Infantry, crossed and occupied the high ground south of the bridge around OCKENFELS (F673200) in order to deny the enemy use of the locality for observation on the bridge.

080715 March

14th Tank Battalion, less Company A, crossed and went into mobile reserve.2 During the remainder of the day of 8 March, the 47th Infantry, 9th Infantry Division, crossed and took up defensive positions to the east and northeast of the 27th and 52d Armored Infantry Battalions. By this time, the bridgehead was about one mile deep and two miles wide.

Following the 47th Infantry, the 311th Infantry, 78th Division, crossed the river and went into an assembly area at (F647213).[3][4]

During the night of 8-9 March, traffic congestion in REMAGEN became so bad that only one battalion of the 60th Infantry was able to cross the river. One cause of the increased traffic difficulty was the almost continuous artillery fire falling on the bridge and bridgehead, and the air strikes in the area.[5][6]

The command of the bridgehead changed twice in 26 hours. At 080001 March, the Commanding General, Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division (General Hoge), assumed command of the forces east of the RHINE. During the night of 7-8 March, he moved to the east bank all command posts of units having troops across the river, so that a coordinated fight could continue even if the bridge were blown. At 090235 March, the Commanding General, 9th Infantry Division (General Craig), assumed command of the bridgehead forces, and directed the operation until the breakout on 22 March.[7]

[1]After Action Report, 52d Armored Infantry Battalion, page 3.

[2]After Action Report, 14th Tank Battalion, March 1945, page 15.

[3]After Action Report, CCB, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, page 9.

[4]After Action Report, CCB, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, page 10.

[5]After Action Report, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, page 20.

[6]Statement of Lt John Grimball, Company A, 14th Tank Battalion: "...the first round of German artillery fired at the bridge came in on the morning of March 8 at about 1030 or 1100 o'clock. I remember this very clearly . .

[7]After Action Report, CCB, 9th Armored Division, March 1945, pages 10, 11.

NARRATIVE: Build-up and Conduct of the Bridgehead

By the time the 9th Infantry Division assumed command of the bridgehead, it had become a major effort. The activities which then dominated the scene were threefold: (1) the close-in protection of the bridge and the building of additional crossings; (2) the enlarging of the bridgehead; and (3) the reinforcing of the troops east of the RHINE. In order to understand correctly these problems and their solution, it is necessary to hark back several days and study the progressive situation.

6 March 1945

In the 9th Infantry Division zone the 47th Infantry Regiment drove approximately three miles past HEIMERZHEIM (F4135), a gain of five miles. The 60th Infantry attacked through the 39th Infantry Regiment and also advanced approximately five miles to BUSCH=HOVEN (F4631), which was captured.

Both Combat Command A and Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division attacked to the southeast early in the morning, and continued the attack through the day and night to advance nine or ten miles. Although Combat Command A was held up for a number of hours at the city of RHEINBACH (F4425), it captured that place during the late morning and by midnight had taken VETTELHOVEN (F5219) and BOLINGEN (F5319). Combat Command B captured MIEL (F4230) and MORENHOVEN (F4430), and by 1530 had entered STADT MECKENHEIM (F4925).

The 78th Infantry Division's 311th Infantry, which had crossed the corps southern boundary into the V Corps zone in order to perform reconnaissance and protect the corps south flank, was relieved early by elements of the V Corps and attacked to the east. The regiment advanced up to five miles to MERZ-BACH (F4322), QUECKENBERG (F4022) LOCH (F4022), and EICHEN (F4216).

As a result of the changes of corps boundaries that had been directed by First US Army during the night 5-6 March, the direction of attack was changed to the southeast, with consequent changes in division boundaries and objectives. The 1st Infantry Division's southern boundary was moved south so that the city of BONN (F5437) fell within the division zone, and the division was directed to seize BONN and cut by fire the RHINE RIVER bridge at that place. The southern boundary of the 9th Infantry Division was also turned southeast so that the cities of BAD GODESBURG (F.5932) and LANNESDORF (F6129) became its objectives, and the 9th Armored Division was directed to seize REMAGEN (F6420) and crossings over the AHR RIVER in the vicinity of SINZIG (F6516), HEIMERSHEIM (F6016), and BAD NEUENAHR (F5716). The 78th Infantry Division was directed to seize crossings over the AHR RIVER at AHRWEILER (F5416) and places to the west of AHRWEILER (F5416), and was instructed to continue to protect the III Corps right flank. All divisions were directed to clear the enemy from the west bank of the RHINE RIVER in their respective zones, and all artillery was directed that pozit or time fuses only would be used when firing on RHINE RIVER bridges.

During the night of 6-7 March, 9th Armored Division was directed to make its main effort toward the towns of REMAGEN and BAD NEUENAHR, and was informed that closing to the RHINE RIVER at MEHLEM (F6129) was of secondary importance.

By 1900, First US Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Courtney H. Hodges, requested the Air Force not to bomb either BONN or BAD GODESBURG. It was also requested that all the RHINE RIVER bridges in III Corps zone be excluded from bombing, although no objection was made to attacking ferry sites, pontoon bridges, boats, or barges being used to ferry men and equipment across the RHINE RIVER.

The III Corps command post opened at ZULPICH (F2333) at 1200.

7 March 1945

Corps continued its rapid advance of the preceding day and drove from five to 12 miles along its entire front to seize the railroad bridge across the RHINE RIVER at REMAGEN (F6420), as well as a number of crossings over the AHR RIVER in the vicinity of SINZIC (F6516), BAD NEUENAHR (F5716), HEIMERSHEIM (F6016), and AHRWEILER (F5416). On this day, enemy resistance appeared to collapse, and opposition was scattered with no apparent organized lines of defense. The little resistance encountered was confined to towns, where small groups defended with small-arms fire, although at HEIMERSHEIM and BAD NEUENAHR the enemy defended stubbornly.

At 1400, III Corps was assigned a new mission when Major General W. B. Kean, Chief of Staff, First US Army, visited the corps command post at ZULPICH with instructions directing the corps to advance south along the west bank of the RHINE RIVER and effect a junction with the Third US Army, which was driving north toward the RHINE at a point only a few miles south of the III Corps right flank. A message cancelling this mission was received at III Corps headquarters at approximately 1845 when Brigadier General T. C. Thorsen, G-3, First US Army, in a telephone message, directed that "Corps seize crossings on the AHR RIVER, but do not move south of the road, KESSELING (F4909)-STAFFEL (F5109)-RAMERSBACH (F5410)-KONIGSFELD (F6011), except on First US Army order." A second telephone call from First US Army at approximately 2015 informed HI Corps that it had been relieved of its mission to the south, but that the III Corps was to secure its bridges over the AHR RIVER, where lt would be relieved as soon as possible by elements of the 2d Infantrv Division (V Corps).

In the zone of the 9th Infantry Division, the 60th Infantry Regiment attacked in the direction of BONN, while the 39th Infantry Regiment continued to attack toward BAD GODESBERG (F5932). By midnight, after advances of several miles, elements were in position to attack BAD GODESBERG and objectives to the south along the RHINE.

To the south, in the zone of the 79th Infantry Division, the 309th Infantry Regiment attacked through the 311th Infantry Regiment, and advanced from eight to ten miles against light resistance and seized crossings over the AHR RIVER.

The 9th Armored Division, having been given the mission of seizing REMAGEN and crossings over the AHR, moved out in the morning with Combat Command A on the right and Combat Command B on the left. The mission of Combat Command A was to seize crossings at BAD NEUENAHR and HEIMERSHEIM, while Combat Command B was to take REMAGEN and KRIPP (F6718) and seize crossings over the AHR at SINZIG and BODENDORF (F63I7). Combat Command B consequently attacked in two columns, one in the direction of each of its objectives, with 1st Battalion, 310th Infantry, and a tank destroyer company covering the left flank. Although Combat Command A met stiff opposition at BAD NEUENAHR, Combat Command B met practically none and captured SINZIG and BODENDORF (F6317) by noon with bridges intact, and by 1530 had captured REMAGEN, against light opposition. Upon finding the bridge at REMAGEN intact, Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Engeman, commanding the north column of Combat Command B, seized the bridge.

First news of the seizure of the bridge arrived at the III Corps command post at approximately 1700 when Colonel James H. Phillips, Chief of Staff, received a telephone call from Colonel Harry Johnson, Chief of Staff, 9th Armored Division. Colonel Phillips was informed that the bridge was taken intact, and was asked for instructions. At this time, the corps commander was at the command post of the 78th Infantry Division, and although First US Army had given no instructions regarding the capture of the bridge, Colonel Phillips gave instructions for the 9th Armored Division (less CCA) to exploit the bridgehead as far as possible, but to hold SINZIG. Colonel Phillips then relayed the information to Major General Milliken, who confirmed these instructions and immediately made plans to motorize the 47th Infantry Regiment (9th Infantry Division) and dispatch it to REMAGEN. The 311th Infantry Regiment of the 78th Infantry Division was alerted for movement to the bridgehead.

Ill Corps was presented with the problem of making troops available for immediate employment in the bridgehead. The greater parts of all three divisions were engaged. As an expedient, units had to be moved to the bridgehead in the order in which they could be made available. In order to achieve effective control and unity of command, it was decided to attach all units initially, as they crossed the river, to Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, for securing the initial bridgehead.

As a result, the 47th Infantry Regiment, having been motorized, became attached to Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, at 2100; and the 78th Infantry Division was instructed to have the Commanding Officer, 311th Infantry Regiment, with necessary staff officers, report to the Commanding General, 9th Armored Division. The 78th Infantry Division was told that III Corps would furnish trucks to the regiment at 080100 March, and that movement would be upon call of the Commanding General, 9th Armored Division. First US Army, on being notified of the day's developments, confirmed the decision to exploit the bridgehead. A telephone call to III Corps from First Army at 2015 included the information that the 7th Armored Division was attached to III Corps immediately, for use in relieving the 9th Infantry Division; that elements of the 2d Infantry Division (V Corps) would relieve the 78th Infantry Division and CCA of the Eth Armored Division as soon as possible; that a new V-III Corps boundary was placed in effect immediately; and that First Army was sending a 90-mm antiaircraft battalion, a treadway bridge company, and a DUKW company to III Corps.

Major General Robert W. Hasbrouck, Commanding General, 7th Armored Division, was instructed to immediately move one combat command, reinforced by one battalion of infantry, to an area MIEL (F4230)-MOREN-HOVEN (F4430)-BUSCHHOVEN (F4631)-DUNSTEKOVEN (F4333), where it would become attached temporarily to the 9th Infantry Division. In turn, the 9th Infantry Division was informed of these arrangements, and was directed that the 60th Infantry Regiment, after relief by Combat Command A, 7th Armored Division, would become attached to the 9th Armored Division.

Other considerations were the need for artillery support, the protection of the bridge against enemy air action and sabotage, the construction of additional bridges, and the problems of signal communication. The signal plan had been built around an axis of advance to the south and did not envisage a need for extensive communications in the REMAGEN area.

Artillery plans also needed quick revision. By 2230, one 4.5-inch gun battalion, one 155-mm gun battalion, and one S-inch howitzer battalion were in position, ready to deliver fire. Heavy interdiction fires around the bridgehead were planned.

By 080300 March the 482d Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion had established defense of the bridge. Assurance was given by First Army that air cover would be provided from any base on the continent or in the United Kingdom from which planes were able to leave the ground.

Visibility during the day was fair, with low clouds and scattered rains throughout. Heavy rains fell during the night.

8 March 1945

Activity on 8 March was concerned primarily with reinforcing the troops across the river as rapidly as possible, expanding the bridgehead, and clearing the enemy from the west bank of the RHINE.

East of the RHINE the enemy took no concerted action. No counterattacks were launched and no organized defenses were encountered. KASBACH (F6620) and UNKEL (F6322) were captured, and at the day's end, the 1st Battalion, 310th Infantry Regiment, was fighting in LINZ (F6718). The 47th Infantry Regiment crossed the river in the afternoon and went into positions northeast of the 52d Armored Infantry Battalion.

The 78th Infantry Division was directed at 0200 to cancel all attacks which had been scheduled for this day, and to hold the AHR RIVER bridgehead until relief had been effected by the 2d Infantry Division. Major General Walter M. Robertson, Commanding General, 2d Infantry Division, had visited the 78th Infantry Division command post, and had stated that the relief could be completed no earlier than 0815 of that day.

At this time the 309th Infantry Regiment was the only regiment under control of the 78th Infantry Division which was actually engaged. The 310th Infantry Regiment had previously been attached to the 9th Armored Division, with which it was currently operating, and the 311th Infantry Regiment, having been alerted for movement on the preceding night, had been assembled and was prepared to move by 0500. Movement of the 311th Infantry Regiment began during the morning and by late afternoon the regiment closed in the bridgehead area, where it became attached to the 9th Armored Division.

At 0945, the 309th Infantry Regiment was alerted for movement to the bridgehead, when

instructions were issued to Major General Edwin P. Parker, Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, directing that the 309th Infantry Regiment, upon relief by the 2d Infantry Division, be assembled and marched on secondary roads to an area designated by Major General Leonard, Commanding General, 9th Armored Division. Major General Parker, Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, was instructed that control of his regiments would be returned to him as soon as he was prepared to assume command of his zone of action in the bridgehead area. At 1755, the relief of the 309th Infantry Regiment was completed, and at that time, control of the zone of the 78th Infantry Division passed to the Commanding General, 2d Infantry Division. At 1815, two battalions of the 309th Infantry Regiment were ordered to move within seven hours, and the regiment began crossing during the night, closing in the bridgehead area on the following day.

Movement of the 7th Armored Division into the zone of the 9th Infantry Division continued throughout the day; and at 1235, Combat Command A had closed in the area and became attached to the 9th Infantry Division. The 1st Battalion, 60th Infantry, had been assembled by afternoon and had crossed the river by early morning of 9 March. Combat Command B, 7th Armored Division, became attached to the 9th Infantry Division at 1100, and was directed to move during the afternoon to relieve the 39th Infantry Regiment. At 1715, the Commanding General, 7th Armored Division, assumed command of the zone, and all 7th Armored Division elements, plus those units of the 9th Infantry Division remaining in the zone, passed to his control.

The anticipated attachment of the 99th Infantry Division made it doubly important that some agency be given the responsibility of staging and moving troops west of the RHINE. Consequently, the Commanding General, 9th Armored Division, was directed to continue to perform this function. The Commanding Generals, 9th Infantry and 9th Armored Divisions, operated as a team, one furnishing troops to the other as called for. HI Corps set up the priority for the movements of troops available west of the RHINE as rapidly as they could be disengaged, and established a tactical command post at REMAGEN to (1) expedite information to corps, (2) give advice for solution of rising problems, (3) closely supervise engineer operations, and (4) supervise traffic and control roads. A traffic circulation plan was placed in effect in which eastbound traffic moved on northerly roads, which were not under enemy observation, and westbound traffic moved on southerly routes. Thus, loaded vehicles ran less risk of receiving artillery fire. In order that bridge traffic would not be interrupted by westbound ambulance traffic, it was decided that casualties would be returned by LCVPs, DUKWs, and ferries, which were soon placed in operation.

Because of poor weather conditions—the day was cold with rain and low overcast— fighter-bombers were grounded and were unable to furnish cover protection for the bridge. However, the enemy attempted ten raids over the bridge with ten aircraft, eight of which were Stukas. By afternoon, however, the 482d Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion had three batteries at the bridge site with three platoons on the east and three platoons on the west bank of the river, while the 413th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion (90-mm) went into positions on the west bank; and of the ten attacking aircraft, eight were shot down.

Because of the air attacks and the artillery fire, the engineers at the bridge site requested that smoke be employed, and requests were again made of First US Army for a smoke generator unit. Because none was available at this time, however, smoke pots were gathered from all available sources. The 9th Armored Group was ordered to furnish CDLs (search lights mounted on tanks) to assist in protecting the bridge against floating mines, swimmers, riverboats, etc., and depth charges were dropped into the river at five-minute intervals during the night to discourage swimmers bent on demolishing the bridge.

By the end of the day, the forces in the bridgehead consisted of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, the 52d Armored Infantry Battalion, the 14th Tank Battalion, the 47th Infantry Regiment, the 3Hth Infantry Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the 60th Infantry Regiment, the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 310th Infantry Regiment, Company C of the 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion, Troop C of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron, one platoon of Company B of the 9th Armored Engineer Battalion, and one and one half batteries of the 482d Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion. The 309th Infantry Regiment was en route.

Ill Corps Operations Directive No. 10 was published, which established three objectives, known as lines Red, White, and Blue. The seizure of line Red was to prevent small-arms fire from being delivered on the bridge area; when line White had been reached, observed artillery fire would be eliminated; and the seizure of line Blue would prevent medium artillery fire from being delivered on the bridge sites.

9 March 1945

On the third day of the bridgehead operation, enemy opposition east of the RHINE stiffened considerably, as elements of the 11th Panzer Division were contacted on the front. Enemy troops had been reported moving on the autobahn with lights on during the night. Although the 311th Infantry Regiment made good progress to the north, where it made gains of from 2000 to 3000 yards, strong resistance was met in the south and center of the bridgehead, and the enemy attacked with infantry, tanks, and aircraft. Fire of all types was received, and heavy artillery fire landed in the vicinity of the bridge. During the early afternoon, a direct hit on an ammunition truck which was crossing the bridge caused considerable damage, placing the bridge out of operation for several hours. n

On the west of the RHINE, all organized resistance ceased; and at 1125, the 7th Armored Division was able to report that its zone had been cleared of the enemy from boundary to boundary and to the river. Relief of the 60th Infantry Regiment was completed early in the afternoon, and at 1300, that regiment was relieved of attachment to the 7th Armored Division. The regiment, the 1st Battalion of which had crossed to the east of the RHINE the preceding day, closed in the bridgehead during the early morning hours of the 10th. The 39th Infantry Regiment, having captured BAD GODESBERG (F5832), was relieved by elements of the 7th Armored Division by 1800, and prepared to move into the bridgehead on the following day. The 7th Armored Division was directed to outpost islands in the RHINE RIVER at (F627270) and (F632270), opposite HONNEF, and to prevent movement of enemy upstream toward the bridge sites.

Of the 78th Infantry Division, all but the 309th Infantry Regiment and elements of the 310th Infantry Regiment, attached to Combat Command A, 9th Armored Division, had crossed the RHINE on 7 and 8 March. The 309th Infantry Regiment, having begun its movement across the river on 8 March, closed in the bridgehead late in the afternoon of 9 March, and at 0930, elements of the 2d Infantry Division were moving into position to relieve the 310th Infantry Regiment(-) in the AHR RIVER bridgeheads. That relief was completed at approximately 1600. By 100400 March, the 310th Infantry Regiment had crossed completely, and the only elements of the 78th Infantry Division remaining west of the RHINE at that time were the division artillery and spare parts.

During the morning the command post, 9th Infantry Division, opened at ERPEL (F647205). The Commanding General, 9th Infantry^Division, was directed that elements or the 78th Infantry Division currently attached to the 9th Infantry Division would revert to control of the Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, at a time and place agreed upon by the two division commanders, and that the Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, would assume control of the north sector of the bridgehead. The Commanding General, 9th Infantry Division, was instructed early in the morning to continue the attack and to seize line White.

At 1015, the 99th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Walter E. Lauer became attached to III Corps, and during the late afternoon the division began to move into an assembly area in the vicinity of STADT MECKENHEIM (F4925). By midnight, the 393d and 394th Infantry Regiments had closed in the area, and the 395th Infantry Regiment was en route.

Instructions were issued directing: (1) that the 99th Infantry Division (artillery), with the 535th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, the 629th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the 786th Tank Battalion attached, would cross the RHINE, commencing at 102030 March; (2) that the division would pass through elements of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, and attack to the south; and (3) that one infantry regiment (minus one battalion) was not to be committed except on III Corps orders. This regiment, the 395th, was to move to an assembly area within one hour's marching distance of the bridge site, and was to close there by the evening of 11 March.

Elements of the 9th Armored Division, which were holding its bridgehead across the AHR RIVER, were directed: (1) to be prepared to move east of the RHINE on III Corps orders; (2) to continue to protect bridges over the AHR RIVER; and (3) to maintain contact with the 2d Infantry Division (V Corps) on the corps south flank.

The III Corps Engineer was directed to assume control of all engineer activity at the bridge site, thus relieving 9th Armored Division engineers of that responsibility. At the

time, two ferries were already in operation, and a third was nearing completion. Construction had been started at 091030 March on a treadway bridge at (F648202), and it was planned that a heavy pontoon bridge would be built upstream at (F674186) (KRIPP). A contact boom, a log boom, and a net boom, designed to protect the bridge from water-borne objects, were under construction upstream from the bridge.

Early in the day. the 16th Antiaircraft Artillery Group was directed to employ all antiaircraft artillery units for the protection of the bridge, and consequently the antiaircraft defense of the bridge site was strengthened by the arrival of two additional battalions. The 109th Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion became operational on the west bank of the RHINE, and the 634th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion crossed and went into position on the east bank.

The corps command post opened at RHEIN-BACH (F4425) at 1220.

At the close of the day, the forces in the bridgehead had been strengthened by the arrival of the 309th Infantry Regiment, the remainder of the 310th Infantry Regiment, the 60th Infantry Regiment, and additional antiaircraft protection. The antitank defense of the bridgehead had been bolstered by the tank destroyers accompanying the regimental combat teams.

Although no artillery—or at best an occasional battery—had as yet moved east of the RHINE, the artillery of the divisions, as well as corps artillery, supported the operation from positions on the west side.

The day was cold, with visibility restricted by a low overcast which continued throughout the day. No fighter-bombers flew in support of the bridgehead, but medium bombers flew several missions.

10 March 1945

The expansion of the bridgehead continued against stiffening resistance. Very heavy resistance was encountered in the area northeast of BRUCHHAUSEN (F6522), and strong points which delayed the advance were encountered in the entire zone. Fire from small arms, self-propelled weapons, mortars, and artillery was received.

In the north, the 311th Infantry Regiment attacked HONNEF (F6427). The 309th Infantry Regiment, in the northeast portion of the corps zone, advanced some 2000 yards to the east after repulsing one counterattack, and in the center sector the 47th Infantry Regiment received sharp counterattacks which forced a slight withdrawal. The regiment, assisted by the 2d Battalion, 310th Infantry Regiment, repulsed these counterattacks, however, and during the afternoon the 3d Battalion, 310th Infantry Regiment, followed by the 52d Armored Infantry Battalion (attached to the 310th Infantry Regiment), attacked through the 47th Infantry Regiment and advanced up to 1000 yards. The 60th Infantry Regiment, in the southeast, attacked and gained about 1500 yards. Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division (1st Battalion, 310th Infantry Regiment, and 27th Armored Infantry Battalion), plus elements of the 60th Infantry Regiment, attacked south and reached a point about 700 yards south of LINZ (F6718), capturing DATTENBERG (F6817) en route.

The movement of the 9th Infantry Division across the RHINE was completed at 1825, when the 39th Infantry Regiment closed in the bridgehead, in an assembly area in the vicinity of BRUCHHAUSEN (F6522). The Commanding General, 9th Infantry Division, requested that he be relieved of responsibility for the security of the railroad bridge and bridging operations at REMAGEN, and consequently the 14th Cavalry Group was directed to assume that responsibility. Instructions were issued directing the group to move to an assembly area in the vicinity of STADT MECKENHEIM

(F4925)-ARZDORF (F5423)-RINGEN (F5419)-GELSDORF (F5021) on 11 March.

The 99th Infantry Division closed in its assembly area west of the RHINE early in the morning and at 1530 one regimental combat team was directed by the corps to move into the bridgehead. The 394th Infantry Regiment began to cross the RHINE during the night, and at 2100 the corps directed that the remaining two infantry regiments plan to arrive at the bridge on the following morning. Ill Corps directed that the 99th Infantry Division plan to take over in the southern sector of the bridgehead.

III Corps Artillery, reinforced by V and VII Corps Artillery, fired heavy interdiction and counterbattery missions during the day.

11 March 1945

The attack to enlarge the bridgehead progressed slowly against continuous stubborn resistance. Few gains were made in the north and central sectors. The 394th Infantry Regiment, which had completed crossing early in the morning, attacked to the south through Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, and gained up to 3000 yards, capturing LUEBSDORF (F6816) and ARIENDORF (F6814). Elsewhere in the bridgehead, some local objectives were taken and a number of counterattacks, supported by tanks, were repulsed.

The 394th Infantry Regiment, the first of the 99th Infantry Division units to move into the bridgehead, completed its crossing early in the morning and became attached to the 9th Infantry Division at 0730. At 0830, the Assistant Division Commander, 99th Infantry Division, opened an advanced command post with the command post, 9th Infantry Division. By noontime, the 393d Infantry Regiment had closed east of the RHINE. The 395th Infantry Regiment moved out during the early morning hours to an assembly area in the vicinity of BODENDORF (F6317), and at approximately 1230 its 1st Battalion had crossed the RHINE, to be followed during the day by the 2d and 3d Battalions. The division command post opened at L1NZ (F6718), and at 1400 the Commanding General, 99th Infantry Division, assumed control of the southern sector, at which time he assumed command of the 393d and 394th Infantry Regiments. As the attack of 'the 393d and 394th Infantry Regiments progressed to the south and southeast, elements of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, were relieved in the line and began to assemble, preparatory to going into III Corps reserve. The 27th Armored Infantry Battalion assembled in the vicinity of UNKEL (F6322). The 1st Battalion, 310th Infantry Regiment, was detached from Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, and reverted to control of the 9th Infantry Division at 1200. Company A, 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion were attached to Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division. The 395th Infantry Regiment was attached to the 9th Infantry Division effective at 1200 and designated as bridgehead reserve.

The Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, assumed control of the northern portion of the bridgehead at 0900, and at the same time assumed command of the 309th and 311th Infantry Regiments, both of which were attacking. The 310th Infantry Regiment, however, remained attached to the 9th Infantry Division, in whose zone it was heavily engaged. The 39th Infantry Regiment, which was operating in the zone of the 78th Infantry Division, became attached to that division. Effective at 1100, Company C, 90th Chemical Battalion, was attached to the 39th Infantry Regiment. Ill Corps directed the 78th Infantry Division units currently operating in the zone of the 9th Infantry Division, and 9th Infantry Division elements operating in the zone of the 78th, to be relieved and returned to their respective divisions as soon as operational conditions permitted. It was directed that details of relief would be agreed upon by the division commanders concerned.

The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, which had been attached to Combat Command B, 13, 9th Armored Division, remained on a two-hour alert on the west bank of the RHINE.

The 9th Infantry Division, having turned over control of the greater portion of the bridgehead to the commanding generals of the 78th and 99th Infantry Divisions by 1400, continued its operations with the 47th and 60th Infantry Regiments plus the 310th Infantry Regiment of the 78th Infantry Division. Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, and the 395th Infantry Regiment remained attached to the 9th Infantry Division.

The artillery of both the 9th and 7th Armored Divisions fired in support of the bridgehead, and the 7th Armored Division occupied the island in the RHINE at (F62S270). On the east side, the 78th Infantry Division discovered a highway bridge leading to the island at (F632270) and sent patrols to that island, whereupon the 7th Armored Division was relieved of that mission.

In the vicinity of the bridge sites, the enemy made desperate attempts to knock out the railroad bridge and prevent operation of the treadway. The treadway was opened to traffic at 0700, but because of several damaged pontoons, was able to handle only light traffic initially. Artillery fire was heavy throughout the night of 10-11 March and the morning of 11 March. At approximately 0515, the railroad bridge was placed in operation again after having been temporarily closed because of damage from artillery fire. Although it remained in operation throughout the day, the movement of traffic was hazardous because of heavy interdiction fires. During the night of 11 March, an enemy noncommissioned officer with radio was captured near the bridge.

The heavy pontoon bridge at (F673186) (KRIPP) was ready for operation at 1700, but was damaged by an LCVP, and it was 2400 before the bridge was reopened. It was planned to divert traffic to the bridge beginning at 120500 March. The DUKW company and three ferry sites continued to be employed.

The antiaircraft defenses of the bridges were strengthened during the day. The 1:34th Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion became operational on the west bank of the river. Three batteries of the 376th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion went into position on the west side of the river and one on the east. Heavy concentrations were instrumental in breaking up several German counterattacks.

The day was cool with intermittent rain.

12 March 1945

All three divisions attacked to expand the bridgehead in the face of very aggressive and determined enemy resistance. Opposition was encountered from tanks, infantry, self-propelled guns, and fire of all types. A number of counterattacks were repulsed. In the north, the 309th Infantry Regiment was forced to defend in position, and the 311th Infantry Regiment received two counterattacks. At 1200, the 1st Battalion, 310th Infantry Regiment, was detached from the 9th Infantry Division and reverted to control of the 78th Infantry Division. The battalion was then attached to the 311th Infantry Regiment. At 2300 the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion was also attached to the 311th Infantry because of the strong enemy pressure in the regimental zone. The 39th Infantry Regiment (attached to the 78th Infantry Division) attacked, but made little progress.

In the central sector, the 9th Infantry Division made slow progress, although the 60th Infantry Regiment attacked to the outskirts of HARGARTEN (F7120), where heavy fighting took place. The 310th Infantry Regiment (-1st Battalion), after reaching its objective, the high ground in the vicinity of (F690240), received a counterattack and was forced to withdraw.

In the south, however, the 99th Infantry Division met lighter opposition initially. The 393d Infantry Regiment advanced up to 3000 yards to capture GINSTERHAHN (F7219)

and ROTHEKREUZ (F7218). On the high ground north of HONNINGEN strong resistance consisting primarily of self-propelled weapons and small-arms fire was encountered. The 395th Infantry Regiment remained in assembly areas under operational control of the 9th Infantry Division until 1SO0, at which time it came under III Corps control as corps reserve. The 39th Infantry Regiment attacked toward KALENBORN (F7024). The rugged terrain and determined defense prevented the regiment from reaching its objective.

At 1S00, Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, was detached from the 9th Infantry Division and came under III Corps control. The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, upon closing in the bridgehead area at 2300, was attached to the 78th Infantry Division, where it became attached to the 311th Infantry Regiment.

The 7th Armored Division Artillery, reinforced by fires from the division tanks and attached tank destroyers, fired in support of the 78th Infantry Division, while the 9th Armored Division Artillery supported the operations of the 99th Infantry Division. Up to this point in the operations, the artillery had been able to support the division operations from west of the river with excellent results, and by remaining west of the river had eased the resupply problem. On this day, four field artillery battalions, two belonging to the 9th Infantry Division and one each to the 78th and the 99th Infantry Divisions, crossed the river; and a schedule which contemplated the crossing of six additional artillery battalions was set up for 13 March.

A marked decrease in enemy artillery activity was noted during the night of 11-12 March and during the following day.

During the period 120600 to 130600 March, Uie enemy increased his efforts to destroy the bridges by aerial assault. A total of 58 raids were made by 91 planes, 26 of which were shot down and eight of which were damaged

The 14th Cavalry Group assumed the responsibility of guarding the bridge and controlling traffic in the bridging area. The 16th Battalion Fusiliers (Belgian), scheduled to arrive in the III Corps area on 13 March, was attached to the 8th Tank Destroyer Group, which had been charged with the responsibility of guarding rear areas.

At 1315, the III Corps command post moved from RHEINBACH (F4425) to BAD NEUEN-AHR (F5716).

13 March 1945

Expansion of the bridgehead continued to be slow because of extremely difficult terrain and stubborn and aggressive enemy resistance, which included several infantry counterattacks supported by armor. In the south-central sector the enemy employed an estimated 15 tanks, and in the northern area approximately 2100 artillery rounds were received. The terrain in this area consisted of steep slopes, heavily forested areas, and a limited road net, which restricted gains to approximately two kilometers.

The 78th Infantry Division's 311th Infantry Regiment made the day's greatest gains-approximately two kilometers—after repulsing a counterattack of battalion strength. The 309th and 39th Infantry Regiments made some progress, and by dusk the 39th Infantry Regiment had secured observation of the town of KALENBORN (F7024). In the center of the III Corps zone, the 9th Infantry Division attacked along its entire front and made small advances. The 60th Infantry Regiment cleared HARGARTEN (F713206) and continued to advance toward ST KATHERINEN (F7221), but the 310th Infantry Regiment (-1st Battalion), with the 52d Armored Infantry Battalion attached, met heavy resistance from tanks, mortars, and artillery and was unable to take its objective.

The 99th Infantry Division moved out early in the morning, with the 393d Infantry Regiment attacking to the east. At 1300, the 2d Battalion, 395th Infantry Regiment, was released from III Corps reserve and reverted to division control. At 1715, III Corps was notified that the 393d Infantry Regiment was being held back because of the fear of overextending its lines. Ill Corps directed that the attack be pushed to secure the objective. The division was informed that an advance on the part of the 393d Infantry Regiment would assist the advance of the 60th Infantry Regiment (on its left) and that should the need arise, the remainder of the 395th Infantry Regiment would be released from corps reserve and returned to the division. This was done at 1800, although it was directed that one battalion be held in regimental reserve and not be committed except by authority of the corps commander.

During the morning, prior to the release of the 395th Infantry Regiment from corps reserve, both the 395th Infantry Regiment and Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, were directed to prepare counterattack plans for employment in any portion of the corps zone. Routes and assembly areas were to be reconnoitered, and Combat Command B was further ordered to be prepared for attachment to any infantry division through which it might pass.

In an effort to further protect the bridge against enemy waterborne attack, V corps, commanded by Major General Clarence R. Huebner, was informed at 1700 that it was vital to use the utmost vigilance along the river to prevent enemy swimmers, mines, boats, or midget submarines from moving downstream. Ill Corps dispatched technical experts to the zone of the 7th Armored Division, where construction of a cable across the river was under way to assist in converting that cable into torpedo boom. One platoon (four CDLs) from Company C, 738th Tank Battalion, was attached to the 7th Armored Division, and the division was instructed to maintain observation and protection on the river and boom 24 hours per day.

The two military bridges remained in operation throughout the day, but the railroad bridge was closed in order to make permanent repairs necessitated by the damage caused by the initial attempt to blow the bridge, and subsequent damage caused by enemy artillery fire and heavy traffic. The ferry sites, DUKWs and LCVPs remained in operation, but three heavy pontoon battalions were relieved of attachment to III Corps over the objection of the corps engineer, who requested that the corps be permitted to retain at least one.

At 2300, the 9th Infantry Division requested "artificial moonlight" for its operations on the night of 14-15 March, and III Corps arranged to have four lights released to the control of the 9th Infantry Division on the following morning.

The enemy again made a desperate bid to knock out the bridges. Ninety planes made 47 raids between 130600 and 140600 March. Twenty-six planes were destroyed and nine damaged. Enemy artillery activity continued light, but III Corps Artillery, assisted by V and VII Corps Artillery, fired heavy counter-battery programs.

The 400th Armored Field Artillery Battalion and the 667th Field Artillery Battalion were relieved of attachment to the 9th Armored Division and were attached to the 9th and 99th Infantry Divisions respectively. The 9th Armored Division was directed to reinforce the fires of the 99th Infantry Division. The 7th Armored Division was directed to reinforce the fires of the 78th Infantry Division.

The day was cool and clear with good visibility. Six missions were flown in close support of corps, and P-38s flew continuous cover over the bridge sites.

14 March 1945

The attack to expand the bridgehead continued, but progress was again slow because of stubborn enemy resistance and rugged terrain. Although there was no appreciable lessening of resistance, counterattacks were 6 fewer in number and smaller in size than during the past several days; and while resistance in the north was generally light during the first part of the day, opposition became increasingly heavier during the afternoon. The central sector showed a marked decline in small-arms fire, although artillery and mortar fire was particularly heavy. In the south, progress was slowed by what was described as moderate to heavy artillery fire. One counterattack by 40 to 50 dismounted enemy was broken up by friendly artillery fire.

In the zone of the 78th Infantry Division, the 39th Infantry Regiment attacked at 0630 with KALENBORN (F7024) as its objective. It was planned that upon seizing this objective, the regiment would return to control of the 9th Infantry Division. The objective was not taken, and the regiment remained attached to the 78th Infantry Division throughout the day. The attack of the 311th and 309th Infantry Regiments progressed slowly. The 309th Infantry Regiment reached its objectives (1st Battalion, the RJ near HIMBERG (F694281); 2d Battalion, high ground south of AGIDIEN-BERG (F694295); and 3d Battalion, RJ in the vicinity of ROTTBITZE (F700276)). The 3d Battalion was driven off, but resumed the attack to retake its objective after severe hand-to-hand fighting.

In the center, the 9th Infantry Division attacked toward NOTSCHEID (F7122), LORSCHEID (F7221), and KALENBORN (F7024). Although LORSCHEID was entered and some ground was gained toward NOTSCHEID, extremely stiff resistance, which included tanks, rockets, and automatic weapons fire, prevented extensive gains. The 52d Armored Infantry Battalion received counterattacks during the afternoon by infantry supported by approximately ten tanks.

In the south, the 99th Infantry Division attacked with the 393d Infantry Regiment and advanced about 1500 yards. At 1620, III Corps released the 2d Battalion, 395th Infantry Regiment, to division control. The 2d Battalion, 395th Infantry Regiment, began the relief of elements of the 393d Infantry Regiment and continued the attack. At 1700, the 2d Battalion, 393d Infantry Regiment, passed to HI Corps reserve. Patrols from the 394th Infantry Regiment, which was situated on the high ground north of HONNINGEN (F7012), entered the north edge of that town.

The 7th Armored Division completed construction of a double cable across the RHINE. Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, remained in III Corps reserve, and the 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron continued to maintain observation close on the west bank of the RHINE.

At 2200, information was received that First US Army was sending a barrage balloon unit of 25 balloons and 80 men to the bridgehead area to afford further protection against attacks by aircraft.

Ill Corps Artillery continued to support the operations, principally by firing counterbat-tery programs, assisted by V and VII Corps Artillery. Three additional field artillery battalions of division artillery crossed the river.

During the day, information was received from First Army that the 1st Infantry Division (VII) would cross the river through the III Corps zone commencing on 15 March. It was decided that foot troops would be ferried across the river in LCVPs while other elements of the division would cross on the bridges and ferries. First US Army further directed that at 161200 March, control of the 78th Infantry Division would be assumed by VII Corps, commanded by Major General J. Lawton Collins. At that time the boundary in the bridgehead between III and VII Corps would become effective.

Orders were issued to the 78th Infantry Division directing it to select assembly areas for two combat teams of the 1st Infantry Division, which would be occupied on 15 and 16 March.

15 March 1945

As the attack continued and the 78th and 9th Infantry Divisions neared the autobahn, enemy resistance in the central sector continued to be stubborn, although it decreased somewhat in the north and south. The 78th Infantry Division attacked early, and its 311th Infantry Regiment made advances of up to 2000 yards; while the 39th Infantry Regiment at the close of the day had advanced more than 1000 yards to capture SCHWEIFELD (F7026), where it received several counterattacks. The 309th Infantry Regiment by the days end had advanced to within one mile of the autobahn, and had observation of that road.

The 9th Infantry Division cleared NOT-SCHEID and LORSCHEID, although the 60th and 47th Infantry Regiments encountered strong opposition throughout the day. The enemy strove bitterly to resist advances to the autobahn, employing tanks, self-propelled weapons, automatic weapons, and small-arms fire. In the zone of the 99th Infantry Division, however, the enemy showed signs of weakening, as the division made good gains and reached its objectives. HAHNEN (F7318) and HESSELN (F7317) were cleared, and advances of more than 1500 yards were made. At 1200, the 2d Battalion, 393d Infantry Regiment, was released by III Corps to division control, and the 3d Battalion, 395th Infantry Regiment, became corps reserve. Ill Corps directed that the battalion be motorized and moved to a position from which it could be readily employed.

Orders were received from the First US Army that the 7th Armored Division was not to be employed in the bridgehead. Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, remained in corps reserve. The 14th Cavalry Group maintained defenses of the bridges, and controlled traffic at the crossing sites.

Both military bridges remained in operation throughout the day, and repair work was continued on the railway bridge. It was determined that a sag of from six inches to one foot had taken place, and that extensive work would have to be done before the bridge would be ready for use. The ferries, DUKWs and LCVPs continued to operate.

Enemy air activity over the bridge decreased sharply, as only seven raids by 12 aircraft were reported between 150600 and 160600 March. Of the 12 planes, two were destroyed and two damaged. Supporting aircraft flew two missions for III Corps; armed reconnaissance was conducted to the corps front, and P-38's flew continuous over the bridge.

During the day, the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division (VII Corps), completed its crossing, closing in the bridgehead at about 1500. The regiment moved north, and it was planned that the 18th Infantry Regiment would cross the river on 16 March.

First US Army issued a Letter of Instruction, dated 15 March, which established a new boundary between III and VII Corps and designated three objectives: the initial objective; initial bridgehead; and final bridgehead. Ill Corps was directed to continue the attack to secure the initial bridgehead, but no advance was to be made past that point except on First US Army order. The boundary between III and VII Corps was to become effective at 161200 March, at which time control of the 78th Infantry Division was to pass to VII Corps.

As a result of these instructions issued by First US Army, III Corps published Operations Directive No. 16, which confirmed fragmentary orders already issued, announced the new boundaries and objectives, and directed a continuation of the attack to secure the initial objective. It contained these additional instructions: (1) The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion would be detached from the 78th Infantry Division effective 161800 March and would revert to the control of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, in corps reserve; (2) Company B, 90th Chemical Battalion was relieved of attachment to the, 78th Infantry Division; (3) the 170th Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm Howitzer) was attached to the 99th Infantry Division, effective 16 March; and (4) the 7th and 9th Armored Divisions would continue their present missions.

16 March 1945

Although enemy resistance continued stubborn in the central sector, where he resisted bitterly the advance to cut the autobahn, lighter resistance in the south permitted the 99th Infantry Division's 393d Infantry Regiment to advance some 4000 yards to the WE1D RIVER. The 394th Infantry Regiment advanced approximately 2000 yards to the south and entered HONNINGEN (F7012), where house-to-house fighting took place during the night. The 395th Infantry Regiment (-3d Battalion, which remained in corps reserve) attacked to the east to secure the high ground west of the WEID RIVER, capturing three small towns. At the close of the day, the 99th Infantry Division had, on its south, reached the initial objective established by army and at one point had crossed it to secure dominating terrain.

In the zone of the 78th Infantry Division, the advance to cut the autobahn continued. At approximately 0200, the Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, requested the use of two tank platoons to be employed in his attack to the north in the vicinity of ITTENBACH (F668313). The 9th Armored Division consequently was ordered to send two tank platoons to the control of the 78th Infantry Division. The attack was successful; and at approximately 1415, the 309th Infantry Regiment was astride the autobahn. At 0930, the 39th Infantry Regiment reverted to the control of the 9th Infantry Division, at which time the III and VII Corps boundary became effective. The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion was to have reverted to command of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division. its employment during the day prevented this, and permission to retain the battalion temporarily was requested by the Commanding General, 78th Infantry Division, and was granted by the corps. The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion and the two tank platoons were returned to Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, on 17 March.

The 9th Infantry Division in the center of the bridgehead continued its attack early in the morning. By the close of the day, it was fighting in STRODT (F7322) and had captured KALENBORN (F7024) and an objective in the vicinity of (F716238). The 39th Infantry Regiment, upon relief, reverted to control of the Commanding General, 9th Infantry Division. At 0930, the 310th Infantry Regiment reverted to control of the 78th Infantry Division.

At 2230, First US Army gave permission to have the 99th Infantry Division continue the attack to the south if III Corps so desired, and accordingly the 99th Infantry Division was directed on the following morning to continue the attack to the south.

The 18th Infantry Regiment (1st Infantry Division) closed in assembly areas east of the RHINE at about 1300.

17 March 1945

In the northern part of the bridgehead, the expansion continued, advancing from 1000 to 3000 yards against enemy resistance that maintained its stubborn attitude. In the southern part of the zone, greater gains were made against a disorganized enemy. In the zone of the 9th Infantry Division, opposition was encountered from self-propelled guns and tanks supported by infantry, with the enemy using villages and towns as strong points. In the 99th Infantry Division zone, bitter house-to-house fighting took place in HONNINCEN (F7014), but elsewhere only small groups were encountered in towns and in isolated strong points.

The 99th Infantry Division attacked to the south, and both the 393d and 394th Infantry

Regiments moved up rapidly, advancing 2000 and 3000 yards respectively. The 393d Infantry Regiment on its left secured the high ground immediately west of the WEID RIVER, while on its right it seized SOLSCHEID (F7613). Elements of the 394th Infantry Regiment were engaged in house-to-house fighting in HONNINGEN until mid-afternoon. Other elements drove south to take hills at (F753135) and (F716119). The 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron was attached to the 99th Infantry Division in anticipation of a further movement south.

Due to the success of the attack in the zone, and the desire to secure the commanding terrain along the general line SOLSCHEID (F7613) ROCKENFELD (F75H)-HAMMER-STEIN (F7209), permission was requested for that objective. It was also suggested to First US Army that it would be desirable to secure the high ground in the vicinity of RAHMS (F7721). First US Army approved, and on the following day, 18 March, instructions were issued which called for a limited objective attack to the south.

The 9th Infantry Division advanced from 1000 to 2000 yards to the east, cutting the autobahn at (F732372). STRODT was captured, but the high ground to its east, although frequently assaulted, was only partially occupied. VETTELSCHOSS (F7224) was cleared during the night. As there was evidence of a pending counterattack in that vicinity, it was requested by the division that the 52d Armored Infantry Battalion remain under control of the 9th Infantry Division until the situation cleared up. Permission was granted. The enemy attempted to destroy the bridges with two as yet unused devices: Four swimmer saboteurs towing explosives tried to reach the bridges but were either killed or captured; and "V Bombs" made their appearance, six falling in the vicinity of the bridges. The 32d Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron continued its mission of protecting the bridges.

Disaster overtook the sorely abused railway bridge at approximately 1500, when, with no warning, it buckled and collapsed, carrying with it a number of engineer troops who had been making repairs in an attempt to put it back in operation.

In the morning, Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, was directed to assemble in the general area OHLENBERG (F6721)-OCKENFELS (F6720)-LINZ (F6718) (exclusive)-DATTENBERG (F6817), and to revert to the control of the 9th Armored Division effective 172400 March. The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, plus the tank platoons which had been attached to the 78th Infantry Division, returned to the control of the 9th Armored Division during the day. The 52d Armored Infantry Battalion was ordered to revert to the 9th Armored Division as soon as operational conditions permitted. The 9th Armored Division was instructed to prepare plans for the employment of Combat Command B in any sector of III Corps zone east of the RHINE.

Ill Corps Artillery supported corps operations by a heavy counterbattery program, long-range interdiction and harassing fires, and heavy close support fires upon call of the divisions. On this day, Major General James A. Van Fleet assumed command of III Corps.

From 18 March to 22 March, all divisions within the bridgehead attacked to the east and regrouped their forces for the anticipated break-through to come. By this time the autobahn was cut, thus denying the enemy its use. The bridgehead had been expanded to a point where it no longer was considered a bridgehead operation, and a large-scale breakthrough was in the making.

SUMMARY OF OPERATIONS

Of the many highly significant and critical operations which the European Theater produced after the Allied landings on the Normandy Beaches, the seizure by the 9th Armored Division (commanded by Major General John W. Leonard) of the LUDENDORF BRIDGE ranks second to none. Climaxing a swift advance across the COLOGNE PLAIN, the capture of the bridge had a profound influence on the conduct of the war east of the RHINE, and may be said to be one of the greatest single contributing factors to the subsequent early successes of the Allied Forces. By its surprise crossing of the RHINE, that great water barrier, the First US Army secured a foothold on the eastern bank of the RHINE which not only drew enemy troops from the front of Ninth US Army, but served as a springboard for the attack on the heartland of Germany. It undoubtedly made the crossing by the Third Army easier, and contributed to the success of Montgomery's drive to the north. Consequently, this one incident not only overshadowed other First Army activities, but dictated the course of its operations subsequent to 7 March. Prior to that date, units of the First US Army had advanced rapidly across the COLOGNE PLAIN, initially expecting to drive east to the RHINE, and then later to turn south and effect a junction with the Third US Army. This latter plan was upset by the capture of the bridge, and the second phase of the operations-the slow struggle to secure and expand a bridgehead-was begun.