Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

DER ADLER

NUMBER 23. BERLIN, NOVEMBER 18th, 1941

At the Belt Conveyor

Photograph specially taken for the Adler by Dr. Franz

The Bolshevist enemy has been overthrown, but the German aircraft armament industry continues to work at high pressure for the last decisive struggle, for final victory. A view of an assembly shed where the famous Junkers Ju 88 bombers are nearing completion.

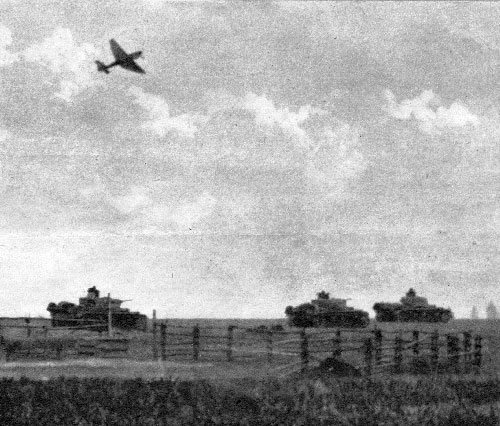

Dive-Bombers Prepare a Breach

Dive-bombers act as flying vanguard of our tanks and attack wherever the Bolshevik troops oppose stubborn resistance to the tempestuous advance of our men. Even the stoutest resistance on the part of the enemy is shattered by the brilliant cooperation of the two branches of the forces in that way.

The stukas do their preparatory work of destruction in the Russian positions, while the tip of the tanks is approaching the enemy. The first machine is just about to dive.

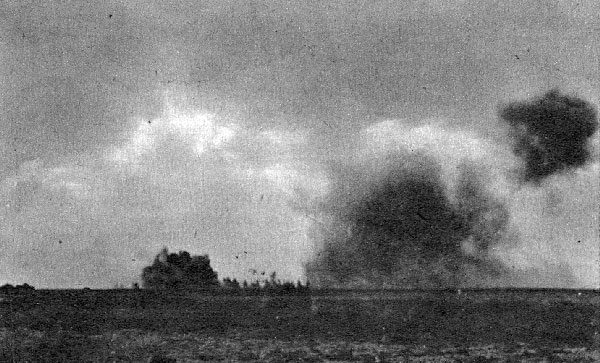

An inferno has broken out over the Soviet positions and a hurricane of flame rushes over them, while the tanks annihilate anything that may be left as they break forth. Stuka bombs land no more than a few hundred yards in front of the tip of the tanks.

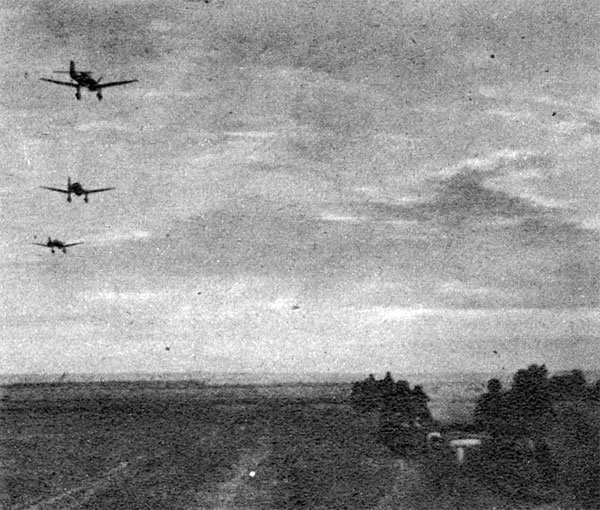

Motor cyclists follow close behind the tanks, while the dive-bombers return from their work of destruction in the Russian positions. The evening meanwhile comes down, but the work has been completed; a breach has been made and the advance can proceed.

Ships' Graveyard Cronstadt

Photographs by war correspondent Freytag, Muller-Engstfeld, Klose, Luftwaffe

The Registrar's Office at the Field Airdrome. The occasion of a "Ferntrauung" (marriage by proxy) at the front is always a bit of a holiday. The squadron has lined up, while the squadron leader carries out the marriage ceremony (in the absence of the bride), at the conclusion of which he presents the newly wed Benedick with a wedding gift in the shape of a sumptuous festal cake.

An offensive spells days of hot work. Flying crews bent on stilling the pangs of hunger need not bother to slip out of their combination suits, because refueling and bombing up the planes between two raids does not take long...

...and then off once more.

Cronstadt, the mighty bulwark of Leningrad, has also had occasion to feel the annihilating force of German air raids.

Photo taken by an observation plane, showing a badly damaged large destroyer of the Leningrad class (1) in tow before the entrance to the harbor and trailing a dense cloud of oily smoke (2). The lengthy shadow of a lighthouse (3) can be seen at the right and an auxiliary vessel (4) at the left.

The battleship "Marat" (1) was split in two by a bomb. Traces of leaking oil can be plainly seen on the surface of the water.

How a Bridge Was Saved

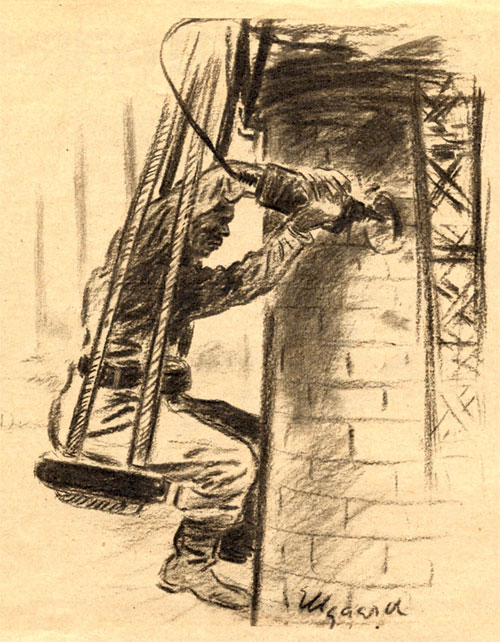

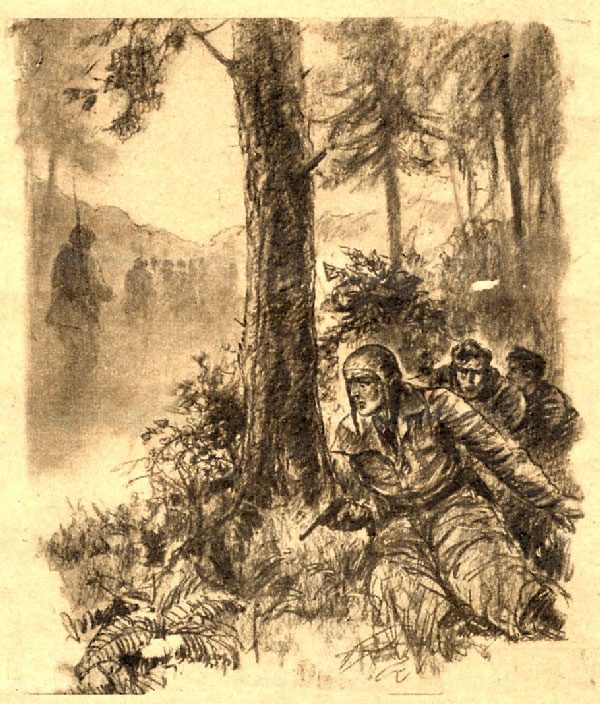

A Ju 87 Bomber Chases Off Bolshevist Dynamitards

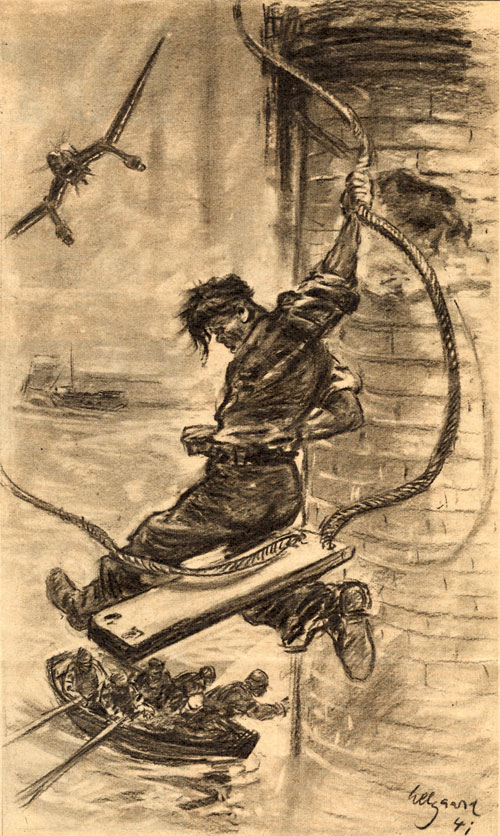

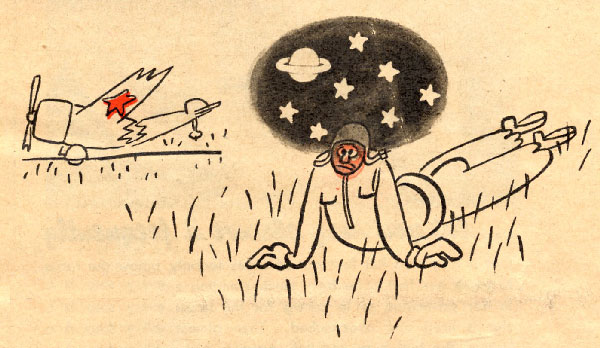

Drawings by Ellgaard, War Correspondent

The following incident occurred on one of the early days of the great decisive offensive in the east, when the German Air Corps was scattering death and destruction over the retreating Russian hosts, lightening the work of the army formations that stuck to their heels. Here and there, however, the enemy still tried to organize resistance. One of these points was a large bridge which the Bolshevists desired to destroy at all cost, In order to hold up the dashing German advance—for a short time at least.

Monster Russian tanks are already roiling up to protect the men detailed to dynamite the bridge. These are clambering up the pillars with great agility, hammering away at the stonework with pneumatic drills and tamping high explosive in the holes. The Germans will be disappointed this time!—But the Germans are determined that the bridge must be saved, come what may! A Ju 87 plane noticed the commotion at the river crossing and hurtled down on the scene.

-

Firing fast and furiously, it struck terror into the surprised dynamitards, bringing them down from the pillars and railings. In spite of that, the survivors try to carry out their mission, but the dive-bomber keeps a strict lookout and curves and circles round the bridge for almost an hour, firing every now and again, until the first German tanks appear.

The bridge is saved. Heavy blows break the last resistance of the Bolshevists, and the German advance can proceed unchecked.

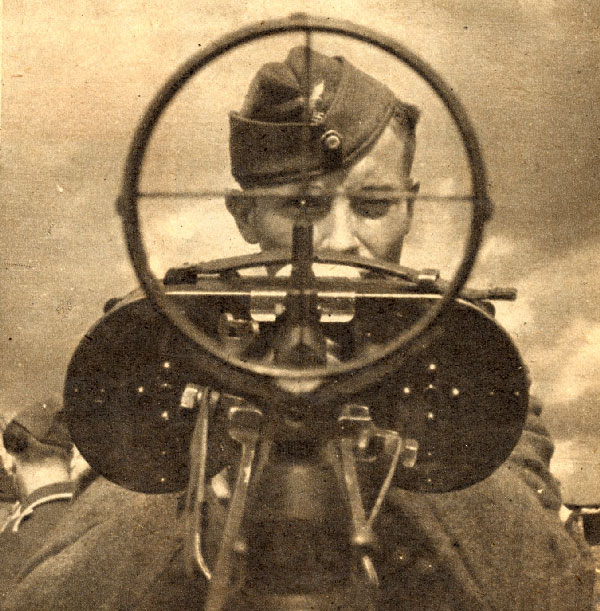

Streamlined Glass Bow Turrets for Our Airmen

Photographs by Hartmann (Mauritius)

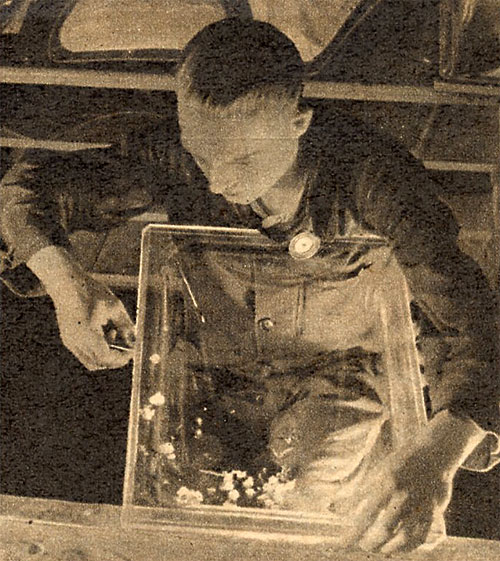

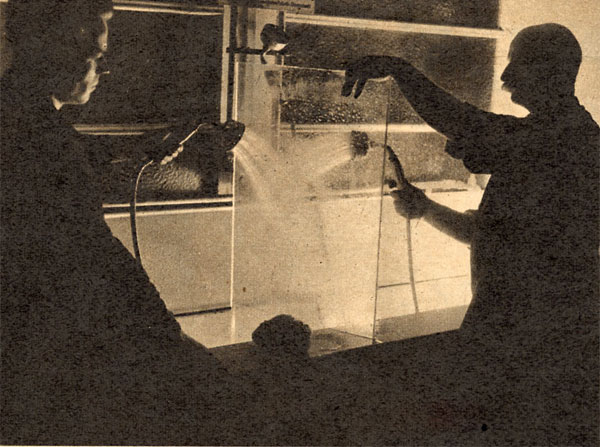

The invention of Plexiglas has made it possible to provide our airmen in the bow turret of their plane with a perfectly clear horizon, giving them a good view in every direction, unimpeded by struts and metal parts.

This pane of glass has a particularly complicated shape and must be machined accurately to one twenty-fifth of one inch.

The streamlined glass turrets arc given their final polish by means of a "chamois leather".

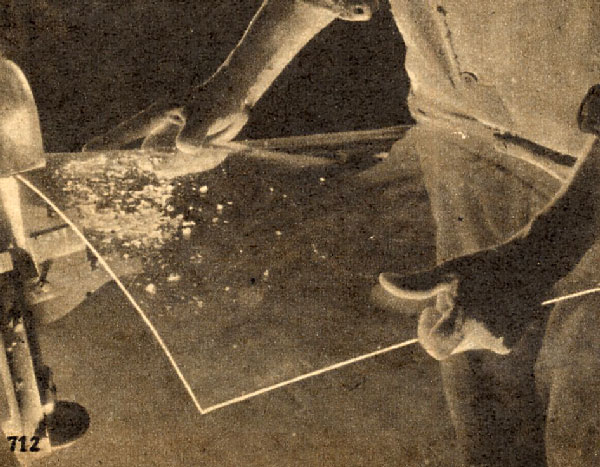

A window pane of flat Plexiglas, from which the most complicated shapes arc bent for glazing the turret.

Small parts of the turret with full visibility are attached to a wooden mold by means of clamps, in order to mold them to their final shape.

A thick pane has been bent and is being accurately cut to shape by means of a specially designed machine.

A worker is busy milling a convex pane according to plan.

One of the huge "glass windows" for our bombers is ready to receive its final polish before installation in the plane.

Past Masters of Aerobatics

Advanced Flying

By GERHARD MEYER

Photographs by Bilderdienst, Waldmann, v. Perckhammer-Scherl, Fieseler-Werkbild, Drawings by Rud. Wenzlow

Udet and Fieseler, the two men in whose personality the most brilliant epochs of German aerobatics are bounted, graduated as fighter pilots. That would seem to hint at connections which place aerobatics, the finest flower of peacetime flying, in the midst of the seriousness and tragedy of war. And such is actually the case. Aerobatics are not merely stunt flying, a striving after empty effect, but the highest cultivation of flying, which, like every ultimate artistic deepening and refinement, makes one proviso—perfect mastery of the instrument, that is, of the airplane. Aerobatics and pursuit flight therewith coincide. The fighter pilot must also be able to master with somnambulistic certainty the thousand horse-power that draw him thunderously through the air.

The soaring leaps and plunges of aerobatics are marked on thc sky by long trails of smoke. Acrobatics in formation flight form one of thc most beautiful, but also one of the most dangerous maneuvers in the air. Thc Italian fighter pilots, in particular, had brought it to a high pitch of development before the war.

The whole world gaped with astonishment at the capabilities of the airplane when the Frenchman Pegoud, a famous and daring test pilot of Bleriot's school, carried out the first short inverted flights and the first looping. It was a sensation and represented the acme of aerobatics, just as flying altogether at that time belonged to the series of neck breaking circus stunts rather than to the sequence of the serious and beautiful deeds of human progress. Udet rose from German soil and wove in the sky a thunderous pathway of curves formed of rolls and loops. Aerobatics were still a sensation. But they no longer displayed the daring of an individual, and showed the perfection that flying had attained. It was the individual, the airman, to be sure, who exhausted the highly developed possibilities of the airplane.

Meanwhile the rumble of the guns on the western front was reverberating over the earth in the gigantic struggle of the Great War in which the airplane grew from an unwieldy, fragile kite to a weapon that dominated space and time. The fighting, conquering, and dying of the airmen at the front had added nothing to aerobatics. On one occasion only Generaloberst Udet, as he tells us, gained a victory in the air by aerobatics. He was hard behind an American who started looping at a height of barely 330 feet, in order to escape the bursts of fire of the German pilot. Udet's heavy Fokker followed immediately and Udet felt a right blow at the apex of the loop. He pulled out his biplane and, upon looking down again, saw the American crawling out of the debris of his plane. The wheels of the powerful Fokker had just touched the top of the upper wing of the enemy plane and therewith brought it down. But that was an exception. The mission of a fighter pilot is not flying, but to shoot down his opponent, and that can be done without looping. One aerobatic figure alone, known as the Immelman turn, which besides is not generally regarded as an aerobatic figure, has been derived from aerial combat. Immelmann, the eagle of Lille, was accustomed to pull up his Fokker, at the same time rolling it on its back, and then righting himself in a semi-looping. He had therewith carried out the quickest right about turn that is possible at all, so that he frequently alighted unexpectedly, as it were, on the neck of his opponent. The roll, that other fundamental aerobatic figure, whereby a plane whizzes through space with horizontal fuselage, but simultaneously rotates about its axis like a projectile, had also been flown before the Great War.

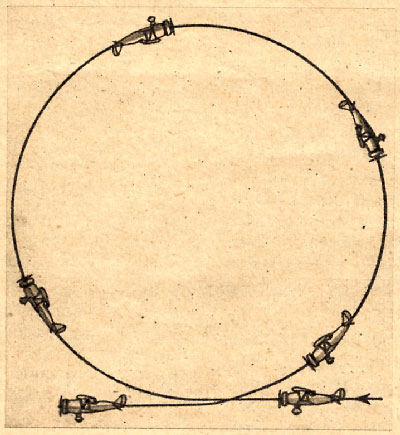

The oldest acrobatic figure is the ordinary loop, whereby the plane flies upward to form a vertical circle.

In the inverted loop forward the plane drops head downwards, but is then compelled to

describe an inverted circular path like that of

thc ordinary loop. The figure was long held

to impossible and was flown for the first

time by Fieseler.

There were thus three, or really even only two aerobatic figures, the loop, the roll, and the Immelmann turn consisting of a semi-roll followed by a semi-loop, upon which the airmen of the post-war time had to build up their aerobatics. There was, to be sure, another stunt that astonished the masses and made them gape. That was spinning, whereby the plane suddenly rears, tips sideways, sideslips, and spins vertically earthwards, while continuously rotating in a narrow spiral. It falls, but the rotation ceases at the last moment. It hurtles vertically to the earth in a nose dive, but is pulled out in time, while the sonorous song of the engine sets in again, and the plane thunders in a daring loop past the grandstand at almost touching distance.

The spin, however, plays no part, or only a very subordinate one in exhibition flying in Germany and in other countries also, because the spinning properties of a plane have been determined once and for all. The pilot can begin or turn a spin, which resembles a drop out of control, by certain movements of the control surfaces, but he cannot influence the spin itself, or only to a very limited extent. Aviation has lost many a good, experienced pilot, notably test pilots, by spinning, and aviation scientists are even today reticent in their expressions on that difficult position of flight. Closer examination moreover shows that the roll, in the form in which it was known at that time, is also nothing but a spin, though certainly in the horizontal direction. A series of such controlled rolls gives rise to the same corkscrew spiral as spinning, although, to be sure, in the horizontal plane. The connections are peculiar enough. Spinning or, to speak more correctly, side-slipping, begins when the airflow which streams whistling over the wings suddenly fails to adhere closely, and becomes weak and powerless, detaching itself on the fop side of the wing into vortices and fluttering off. Lift disappears and the plane must drop. Thus an airman about to fly a roll pulls up the nose of the machine a little and levels out until it reaches the position in which the airflow almost becomes detached. Then when the ailerons, or the control surfaces on the wing tips, are shifted, the airflow is actually detached, just as in a spin. But, since the plane has received a powerful rotary swing, owing to the very hard and sudden deflection of the control surfaces, it must rotate horizontally like a projectile, as it flies.

There thus exist only a couple of aerobatic figures! But it was marvellous to see what the pilots made of them at that bitter period of German aviation. Head and shoulders above all, stood Ernst Udet, whose name was familiar to every child at that time from the army bulletins. Crowds of thousands flocked to the flying fields when Udet flew. All that that past-master of aviation had learnt from aerial combat and many years' experience was collected in his exhibition flights to form a splendid experience of flying. He combined rolls, loops, and steep turns to form a series of breathtaking bounds and dives. He would climb with roaring engine steeply into the sky and swing himself earthwards again, almost noiselessly but for the roaring of the relative wind blustering round him, in a whole series of loopings, while the propeller was idle. He would whirl flat over the ground, nip up a handkerchief from the ground with the tip of a wing, to fly next moment upside down over the flying field, and a few seconds later lay once more in a steep bank over the runway. That was flying, such as mankind had dreamt of. Wings have been given to man that enable him to rise into the wind like a bird and exultingly to play with the elements. Was it possible to surpass such feats of flying, could new avenues still be opened up for aerobatics?

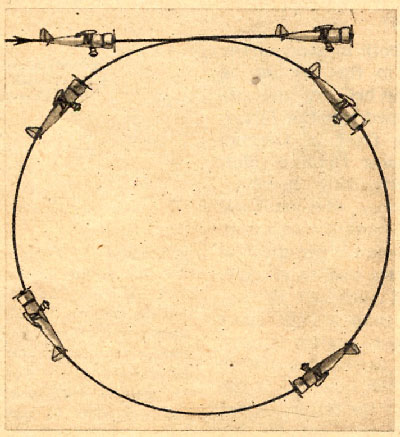

Tn a roll the plane rotates about its longitudinal axis.

In the pulled roll (above), it is compelled to rotate by a sudden upward movement of the aileron, whereby the plane moves forward with an undulating motion. The deflection of the control is not altered during the whole rotation. Each individual phase of the controlled roll (below), on the contrary, is controlled by a perpetually changing combination of a series of various deflections of the control surface.

That is a certain aerobatic figure that can be imagined, but which, it was believed, could certainly never be flown: the inverted loop forward. In the ordinary loop the plane lifts its nose and rises in a steep arc, until it lies on its back for a moment and then closes the circle by whirling downwards in another arc of similar radius. In an inverted loop forward, on the contrary, the plane lowers its nose, drops in an arc, as if rolling downwards on the surface of an invisible sphere, to which it continues to cling, so that it is soon lying on its back, while keeping up its speed, and then zooms up the other side of the sphere. Up to July 23, 1927, the inverted loop forward was held to be an impossibility, but on that date it was flown by a hitherto quite unknown German pilotm the former ace Gerhard Fieseler, who had again taken up flying barely twelve months previously. Pilots held their breadth. Fieseler was awarded second prize at the championship meeting at Zurich, where he was the only pilot to represent Germany against a contingent of the best aviators and planes of the victor states. A jury composed of french and English judges could at that date hardly be expected to award the first prize to a German pilot.

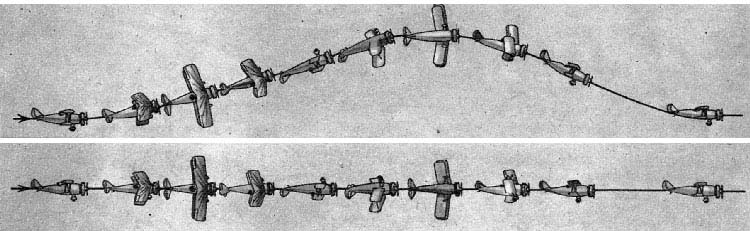

Fieseler flying a controlled roll, a flying figure which he was the first to introduce. He thereby twists the plane, while it continues in horizontal flight, like a spindle about its logitudinal axis, without losing so much as one inch in height.

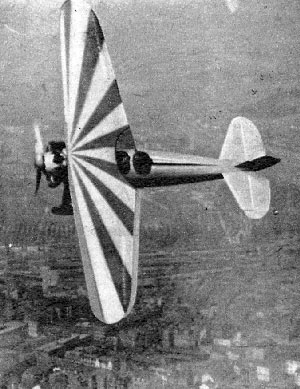

A briliant feat by Ernest udet. The past-master of German aerobatics started the Flamingo in a curve close above the ground and thereby lifted a handkerchief from the ground by means of a device attached to the tip of a wing.

Fieseler astonished the world at Zurich with a couple of sensations at once: the inverted loop forward and the controlled roll. By incredibly delicate manipulation of aileron, in conjunction with rudder and elevator, the effect of which perpetually changes during the rapid rotation of the roll, he succeeded in controlling the roll to such an extent as not to lose an inch in height. He found no imitators at that time.

Aerobatics underwent a rebirth with that meeting at Zurich. Within less than one year Gerhard Fieseler had taken his place in the front rank of aerobactic pilots and seven years later, in 1934, he experienced the greatest triumph of his career as aviator by his victory in the international championship matches at Vincennes in competition with the most famous airmen of the whole world, in particular, the most brilliant English and French military pilots.

It was not the numerous aerobatic figures alone that Fieseler created—practically all the figures of modern aerobatics were flown for the first time by that airman—that made that gifted personality an innovator and the originator of aerobatics, as we know the art today. Fieseler was the pioneer of a quite novel type of flying which was originally taken up with surprise and amazement, until it was recognized for what it really is: the transformation of flying into an art subject not only to the regulations of a sport, but also to as strict esthetic laws as govern skating, or gymnastics. Fieseler has been called the mathematician of aerobatics. For he did not fly according to his mood, or as the whistling of the wind and the roaring of the engine incited him, but had a sheet of paper strapped to his knee on which every figure with exact timing had been noted in a carefully planned sequence, and that is precisely what distinguished him from all previous aerobatic pilots. He flew by stop-watch. And yet his flying was a matter of the most delicate sensitiveness, of careful planning, and of bold daring. It was only possible with the stop-watch in the hand to combine the large number of flying figures at the international championship meeting at Vincennes to form a program that remained in the memory of the world of aviation as a solitary peak of aerobatic achievement, in which no one has emulated the champion down to the present day.

Could Ernst Baier and Maxie Herber be termed mathematicians of skating? And yet the swaying movements of the body, the rhythms of the rapid leaps and bounds are restrained and subdued to form harmonies of mathematical clarity and precision. Fieseler flew in exactly the same way. It was flying in its ultimate perfection. Just as in skating, the figures drawn by the manoeuverable plane of the aerobatic pilot in the sky are coupled to form a necklace of combinations. The vertical figure eight can be built up from the ordinary loop and the inverted loop forward, a ceaseless sequence of controlled rolls can be woven to form roll circles and roll figure eights. Ever new combinations, one more difficult than the other, can be worked out.

General-Oberst Udet, the most successful surviving German ace of the Great War, brought aerobatics to fresh lustre during the years of German bondage. His aerobatics with standing propeller and his breathtaking ground acrobatics, or aerobatics near ground level, were masterpieces, by means of which he gained a brilliant victory for Germany at the National Air. Faces held at Cleveland, U.S.A., in a contest against the superior forces of the best American airmen and planes.

Udet and Fieseler, the two past-masters of German aerobatics, are thoroughly combative natures. They fought in the Great War—although on different fronts— against a common foe. Udet, the ace of aces, became the most successful fighter pilot in the German army on the western front following the immortal Ritt- meister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, while Fieseler, the "Tiger of Macedonia", defended a whole sector of the front in the east against the superior forces of the English and French armies and swept twenty-one opponents from the sky.

By a peculiar dispensation of fate, both masters of the joy-stick defended their country in the sky dicing the post-war years and here also won brilliant victories in competition with the best equipped superior forces. Fieseler announced in Zurich the right of German aviation to live. He arrived as sole German pilot, flew, and conquered—at least morally. Udet, however, one fine day stood with his Flamingo, the aerobatic plane which attained international fame through him, at the National Air Races in Cleveland, the greatest exhibition of American aviation. He had to struggle against the heavy military planes of American, British, and French pilots with no more than a light sport plane; a sparrow had entered the lists against falcons, as he expressed it later. That was the same situation in which Fieseler also keenly felt the bondage of the German people and rebelled against the fetters. Udet was also victorious! Not for himself, not for his Flamingo, but for his country.

Gerhard Fieseler, whose aircraft factory is today turning out the Fieseler "Stork" plane, is the creator of numerous new aerobatic figures. In 1934 he gained the world championship in aerobatics at Vincennes, near Paris, by presenting a program of free flying of his own devising in which he has found no imitator down to the present day.

Manfred von Richthofen once said that one need not be able to fly particularly well, in order to be victorious in air combat, tut-one must be able to fight. That view does not nowadays command complete assent and the tendency is to regard a pilot who can fight and fly as being a good fighter pilot. The result is that no airman is allowed to occupy the pilot's seat of a fighter plane who has not proved by a series of prescribed aerobatic flights that he is able in every situation to master the machine that carries him. The certificate of aerobatics is nowadays a preliminary condition for every course of training on large speedy planes, whether these be intended to carry loads of bombs on raids, or to connect towns and countries on the highroads of air traffic. Of course a military pilot need master only the fundamental figures of aerobatics. It cannot of course be said that a famous aerobatic pilot will also be a successful fighter pilot. Successful fighter flying demands more than merely that! Above all, a stout heart and a martial spirit are essential, besides flying ability. And further a good and sure eye, sharp and light faculty of thinking, and sangfroid at the critical moment.

It is not so much the way in which a curve is flown in an aerial combat, as when it is flown. The neatest curve, controlled with the utmost flying skill, will not protect a pilot from being downed, if started one second too late.

Precisely at the present day, when fighter planes rush on one another at a speed of upwards of six miles a minute and life and death are decided in a split second, a fighter pilot must not be merely a man in a machine, but must be the soul of a complicated technical organism. He must be one with his wings like a bird, so that every sense, every thought is tensed to two things only: his opponent and his gun-sight. The pilot, however, learns and experiences in aerobatics that intimate fusion of man and plane, that instinctive response to the forces of the machine and of nature. That is precisely what makes aerobatics a pillar of the narrow bridge that leads from flying to victory.

HONVEDS of the Air

The Hungarian Air Force in tbe Campaign against the MSI

Photographs by Hungarian Air Force (Oskar Poffel)

Alarm at a Hungarian airdrome. The command to take off has been given and the crews are hurrying to their machines to raid the Russian foe, who has already received many a crushing blow from our ally.

Hungarian airmen, just returned from an attack on Soviet positions, are relating their experiences. To judge by their mood, it must have been a great success.

A bomber of the Caproni Ca 135 type has been got ready for a raid and the crew are climbing on board.

Hungarian fighter planes of the Fiat CR 42 type ready to take off from an airdrome.

Light anti-aircraft artillery arrive at a far advanced field airdrome to protect it against attack by the Russians.

The commander of a successful fighter squadron, himself one of the most successful fighter pilots, mentioned in despatches for conspicuous bravery in the presence of the enemy.

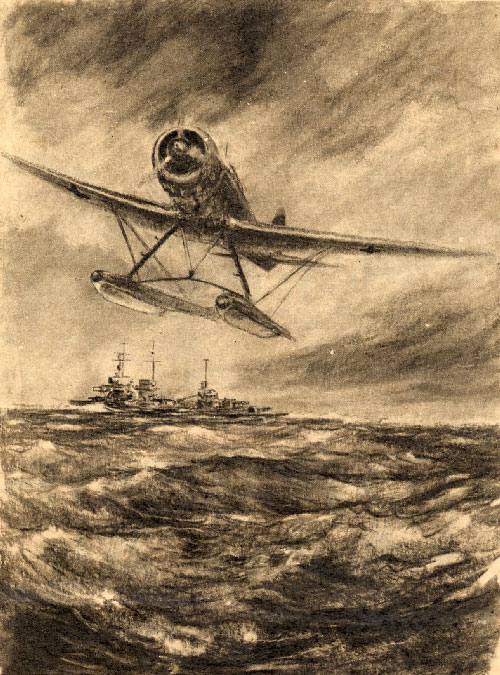

Machine Gun versus Sharks

Adventurous Emergency Landing at Sea

Drawings by H. v. Medvey

The tale of shipboard pilot Heiner briefly narrated here is one of the numerous adventures that form a tiny stone in the mosaic of the great events of war and remain unchronicled, but for the brief remark, "All soldiers did their duty". Very few are aware just how much courage, presence of mind, and adventurous experience are covered by that little word "duty" in each individual case. The chronicler only picks out a chapter at random from the innumerable war diaries when fate behaves unusually capriciously towards one or other. That was pretty much the case with Leutnant zur See (Ensign) Heiner R., whom we will here call shipboard pilot Heiner. The commerce raider for which his machine acts as spotter and reconnaissance plane has been cruising hither and thither over the Atlantic and has for days been searching for a certain definitely specified valuable prize. Today happens to be Heiner's birthday and he takes off with his heart full of hope. The other member of thc crew is Feldwebcl (Sergeant) Y. The young pilot cannot conceive of a finer birthday present than at long last to nose out thc merchantman followed so assidously and send it to the bottom of the sea. His comrades wish him every luck and eagerly await his return with high expectations.

But they watch and wait in vain. The hours pass by. Not a sign of life from the machine, which is long since overdue. Can it really be possible, that something has happened? But no, just on Heiner's birthday, that would be unthinkable. His comrades begin to reckon out the situation; the pilot left at such and such a time, the fuel would last for so many hoursbut puzzle it out as they will, there is no other conclusion, but that the fuel tank must be empty long ago, and it is clearly evident that he has either been shot down or has had to make an emergency landing. And then a wireless message arrives from the missing machine. It is all too brief and runs "Made emergency landing". But whereabouts? Efforts were naturally at once made in the wireless cabin to take bearings on the machine, but the faint distress call had again given out, before thc exact position could be determined. At all events, the ship immediately reverses its course and steers in thc opposite direction, with its engines all out. Thc two pilots must be found before nightfall. Once again, thc hours slip away. Not many words arc lost on thc ship, but the minds of all are heavy. A light haze lies over the sea and hinders visibility

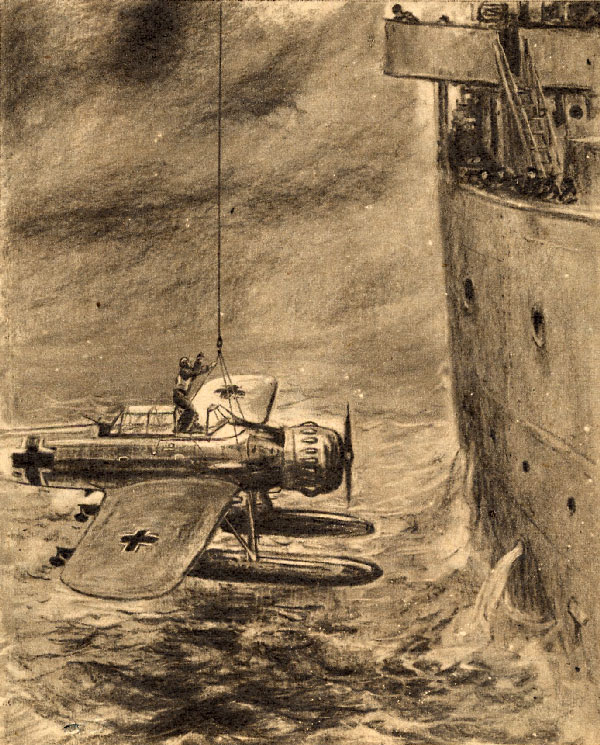

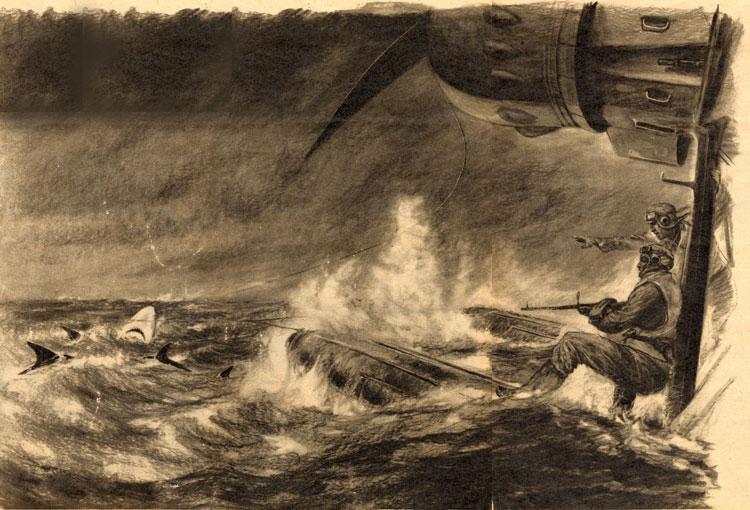

At last! The airplane came into view in the early hours of the everting, tossed about like a ball on the heavy sea. It was soon reached and quickly hoisted on board by means of the crane. Two men climb out, rather the worse of wear. Little wonder either that they are exhausted, because their experiences of the last few hours might well be termed rather ncrveraclcing. Even the emergency landing in the heavy swell of the Atlantic was a daring operation that might well have gone wrong. But worse was to come. Huge dark fins whipped the water shortly after the canvas sea-anchor had been thrown out. The visitors were sharks. Two pilots hardly credited the evidence of their eyes. There were four of the brutes and they came very close up to the floats of the machine, as if greedily waiting for their prey. Without a moment's hesitation the pilots dismounted the stern rear machine gun from its frame, dragged it to thc bow, and brought it into position—which was naturally easier said than done, because the floats were slippery and offered no proper hold for the feet and the airmen, whose hands were occupied with the machine gun, had to squeeze themselves with all their might against the struts, so as not to be swept overboard. The first bursts oftfite went wide, but then the bullets found their billets. The first result was to infuriate the sharks, whose united strength might perhaps have sufficed to capsize the flying boat. But Heiner fied like a Berserker, until the brutes had had enough and hauled off. The water round the siirplane was long ruddy with blood, the traces of a struggle such as is otherwise rather unusual in air combat.

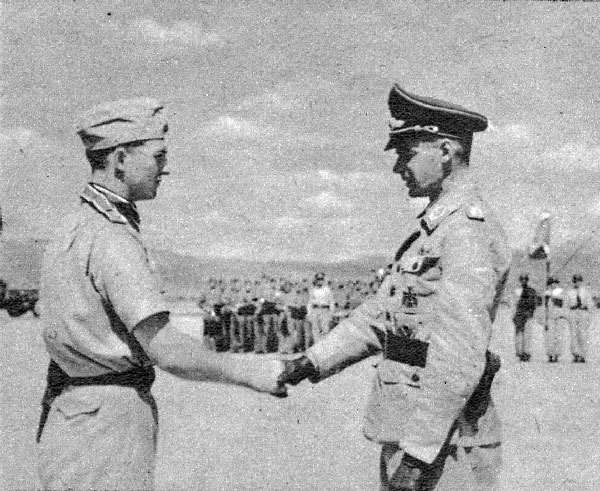

The Day of his Life

Photographs by war correspondent Dr. Petertil

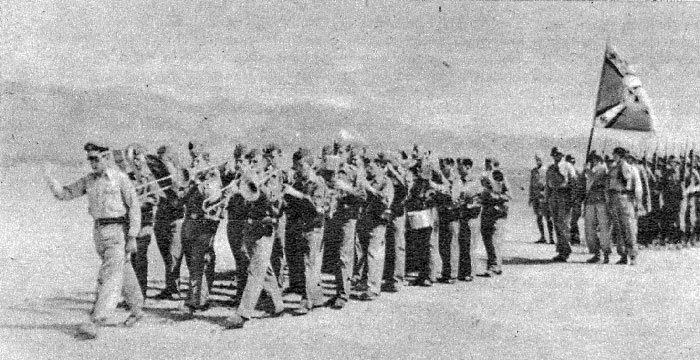

Oberfeldwebel (Top Sergeant) Schlund, radio operator in a bomber wing, has hitherto taken part in two hundred raids and successfully fought off thirteen attacks by enemy figther planes, among other achievements. He was the first radio operator of the German Air Corps to receive the Knighthood Cross of the Iron Cross. Sufficient reacon in all conscience to celebrate such a red-letter day with goose step and the blare of trumpets.

A light breeze is rusding over the field airdrome and blows out the heav; gold-worked flag of the wing carried before the section of honor.

... And then a firm hand-clasp by the group commodore. The men are paraded and the southern sun smile from an azure sky ..

First of all a section of honor marches up, headed by thc band, which opens the great day of the radio operator with the stirring strains of a rousing march.

The group commodore and the wearer of the Knight hood Cross finally pace down the front of th< bomber wing and sections of honor on parade. There with ends the official part of the program, but it ma) probably be assumed that justice is also done to the inofficial part.

How They Won the Knighthood Cross

Photographs Scherl-OKW (IJ). War Correspondents Hug (Scherl), Juttel (Scherl)

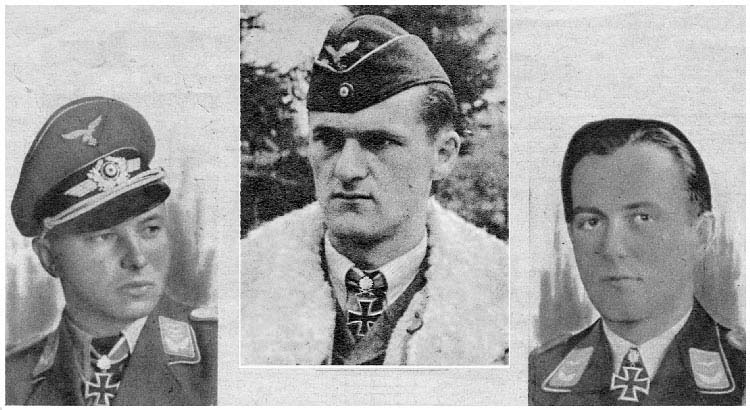

Hauptmann Hahn, Major Lutzow, Leutnat Siegfried Schnell

The Fuhrer and Supreme Commander of the German forces invested Major (Squadron Leader) Lutzow, commodore of a fighter group, with the Oak Leaves with Swords to the Knighthood Cross of the Iron Cross on the occasion of his 89th air victory, being the fourth officer of the German forces to receive that distinction. Hauptmann (Flight Lieutenantl Hahn, commander bf a fighter wing, and leutnant (Pilot Officer) Siegfried Schnell received the Oak Leaves to the Knighthood Cross of the Iron Cross on the occasion of their 42nd and 40th air victory respectively.

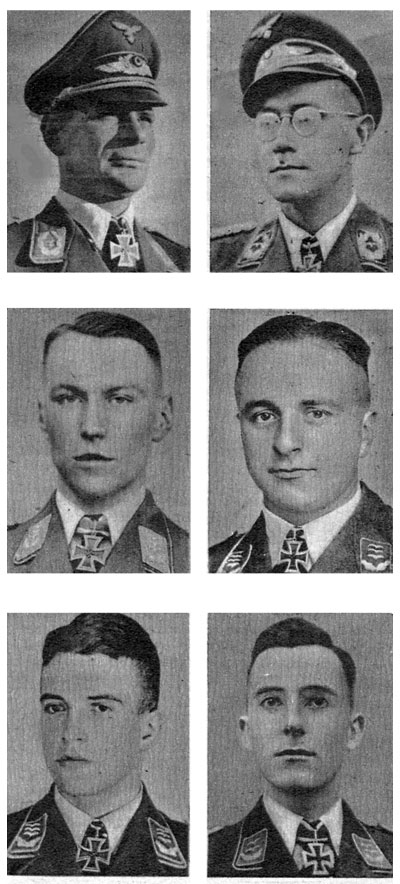

(From left to right). Oberstleutnant Weitkis, Oberstabsartz Dr. Neumann. Hauptman Blasig, hauptmann Bradel, Hauptmann Bruck, Oberleutnant Beyer.

Oberstleutnant (Wing Commander) Weitkus, commodore of a bomber group, has done outstanding deeds of valor in numerous raids on England and during the campaign in the east at the head of his group, and has boldly carried out very successful attacks on enemy shipping. Oberstabsarzt (Major med.) Dr. Neumann jumped off by parachute together with his commander at Maleme airdrome in Crete. He has done his duty as regimental medical officer in a most exemplary way, displaying great personal courage, and has repeatedly tended severely wounded men in the firing line. Hauptmann (Flight Lieutenant) Blasig, wing commander in a dive-bomber group, has led his men in conspicuously successful raids. The occupation of the fortress of Salla in the theatre of war in Finland was mainly due to his prudent leadership and personal courage. Hauptmann (Flight Lieutenant) Bradel, squadron leader in a bomber group, among other daring deeds, succeeded by bold low-altitude flights in frustrating a threatening attack by about 500 tanks during the tank battle of Grodno, whereby he and his squadron displayed the utmost gallantry. Hauptmann (Flight Lieutenant) Bruck, squadron leader in a dive-bomber group, has led his formation in more than sixty raids in every theatre of war in the thick of the battle. His unusual energy makes him a born leader whose verve continually carries his men to fresh achievements. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Beyer, squadron leader in a fighter group, has won 32 air victories and destroyed ten enemy machines on the ground by low-flying attacks boldly carried out.

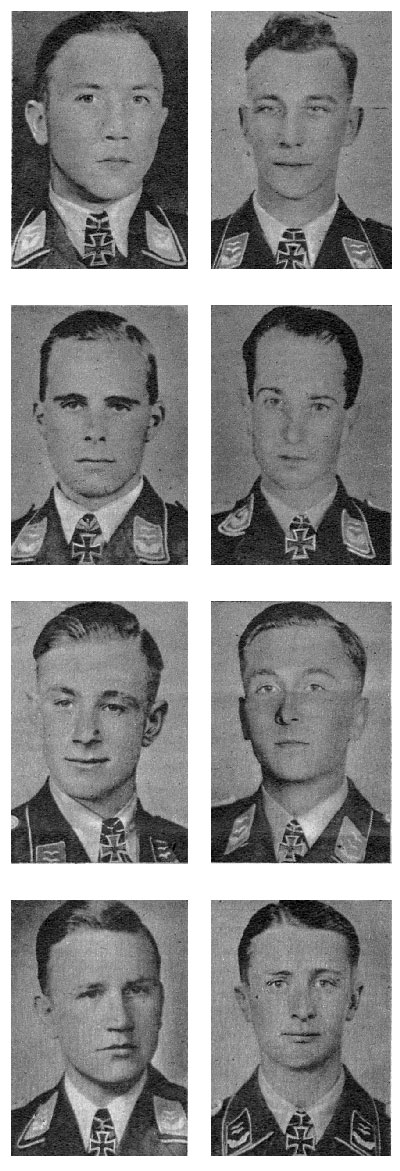

(From left to right). Oberleutnant Druschel, Oberleutnant Grasser, Oberleutnant Lent, Oberleutnant Schairer, Oberl. Karl-Heinz Schnell, Oberleutnant Steinhoff.

Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Dorffel, squadron leader in a ground strafer group, has shown exemplary dash and verve during the campaign in the east. In particular, he took a decisive part in the ground fighting at Vitebsk and his reckless daring more than once relieved the pressure on ground troops in difficult situations. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Dornbrack, squadron leader in a ground strafer group, distinguished himself by conspicuous bravery particularly in the battle of Bialystok. In spite of very heavy anti-aircraft fire, he and his men succeeded by attacks in relays in destroying the advanced points of the fleeing enemy, causing great panic and bringing the retreat to a stop, thereby decisively contributing to the complete surrounding and annihilation of the enemy. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Druschel, squadron leader in a ground strafer group, proved his unrivalled courage and contempt of death also in the east. Thus squadron, for example, nipped in the bud a flank attack by hostile tanks south of Grodno. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Grasser, pilot in a fighter group, has 25 air victories to his credit and has caused heavy loss to the enemy in the east by daring low-level attacks. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Lent, squadron leader in a night-fighter group, has shot down seven machines by day and 13 at night. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Schairer, squadron leader in a dive-bomber group, is one of theimost successful dive-bomber squadron leaders and has taken part in more than 150 raids. During the campaign in the east he has signally contributed to the annihilation of the enemy. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Karl-Heinz Schnell, squadron leader in a fighter group, has taken part in numerous air combats, in which he shot down 29 enemy planes, and has proved his daring in successful low-flying attacks. Oberleutnant (Flying Officer) Steinhoff, squadron leader in a fighter group, has shot down 26 hostile planes. His work as escort In more than sixty raids on England is particularly noteworthy.

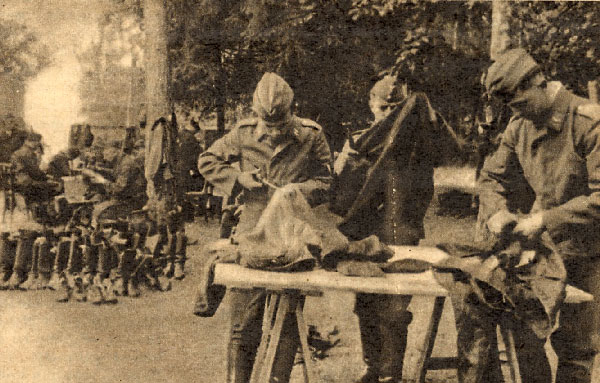

The Travelling Wardrobe

Photographs by the war correspondents Engel, Fromm, Mullner, Sturm.

An anti-aircraft corps assembled a mechanized clothing train which visits the troops at all their widely scattered positions according to schedule, in order to look after the soldiers' garments on the spot. There is a busy time in the bootmakers' shop.

The travelling wardrobe has just arrived at the unit at the front. New articles of clothing are being unpacked, to be exchanged for old ones.

A man who believes in self-help. A foreman among the ground personnel has a brain-wave. His trousers are given the regulation crease, in spite of the lack of a flat-iron.

No sooner has the clothing train arrived than the sewing machines (photo at the left) begin to purr; for the tailors find much work awaiting them. Uniforms and trousers suffer severely during an advance.

The work is soon completed. A few handworkers are still busy with the last few repairs and then the work-tables arc dismounted and the travelling wardrobe proceeds to the next anti-aircraft position.

Before taking off for a new raid.

Photo by Dr. Franz

The machine has been refueled and bombed up, and is now ready to take off. The crew are completing their preparations, helping one another to adjust the parachute harness.

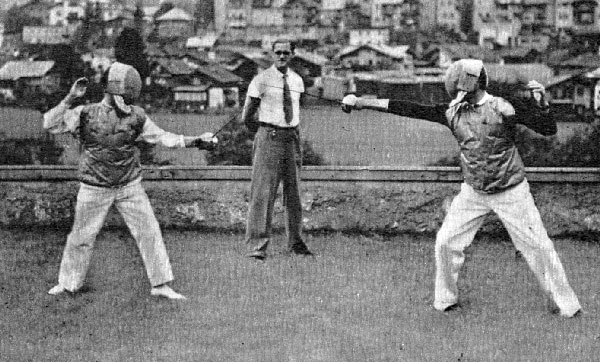

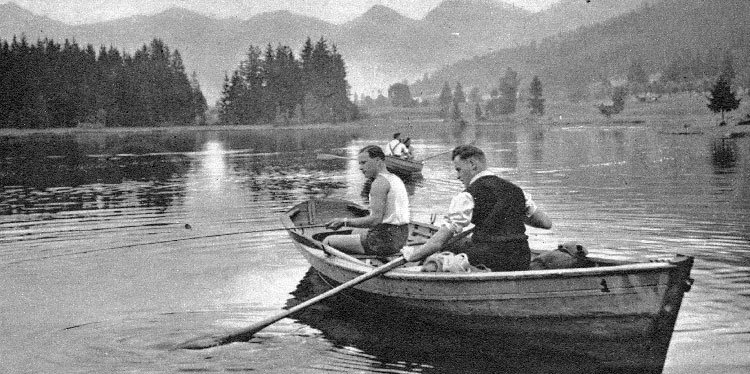

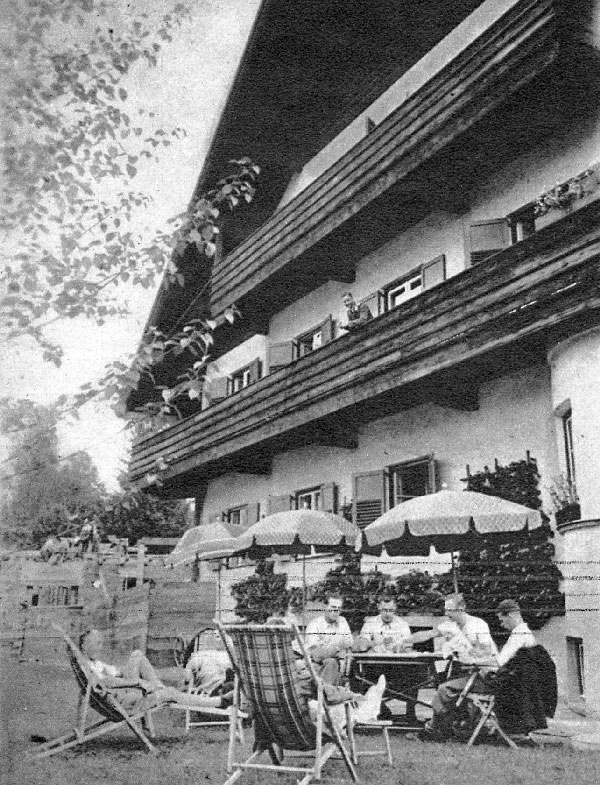

Convalescent Home of the Luftwaffe at Kitzbuhel

Special report by Dr. H. Franz

No more suitable location could well have been found for a convalescent home for the German Air Corps than the popular summer resort of Kitzbuhel, famous chiefly as the paradise of shi-runners in Tirol. It is chiefly intended for the use of crews in need of rest and recuperation after their arduous and exacting duties to restore them to health and vigor by a stay in mountain air and mountain sunshine. The multifarious possibilities of sport afforded, for example, by the mountains and a lake in the neigborhood are thereby of particular importance, apart from a first-class diet.

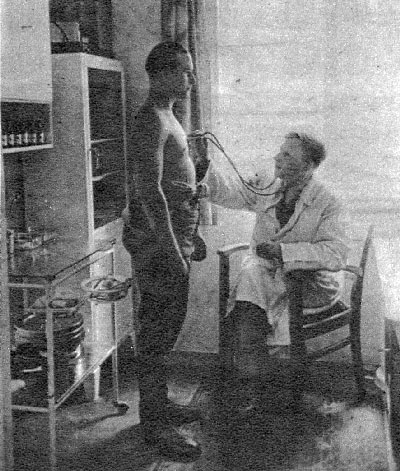

The convalescent home of the Luftwaffe is under the management of a medical officer of the force and is naturally fitted with the necessary medical equipment for the curativc treatment of its guests.

Archery at the Schwarzsee near Kitzbiihel. The various possibilities of sport and games presented to the members of the Luftwaffe in need of recuperation form an important contribution to the restoration of their health at the home.

Fencing in front of the picturesque dropscene of Kitzbuhel. Even in summer this well-known winter playground presents plenty of opportunities of taking part in the most diverse kinds of sports and pastimes, particularly mountaineering, besides rowing and swimming in the Schwarzsee close at hand. Equipment for other forms of sport and games, such as tennis and fencing, is also available.

The rooms of the home are practically and comfortably furnished. The cosy comer of reading room is a favorite resort during the evening hours.

Boating and fishing, for which thc Schwarzsee in the neighborhood presents every opportunity, form a popular way of passing the time among the airmen who seek recovery here from the strain of their strenuous work at the front.

The guests of the home are constantly under medical supervision. They are medically examined on their arrival and departure, as well as once a week during their stay of four to six weeks.

The ping-pong table is frequently the scene of keenly contested competitions carried out under the critical eyes of very alert spectators.

The building in which the Kurheim or home of the Luftwaffe is accomodated was originally a ski sport school and its style is admirably adapted to the character of the landscape.

The Luftwaffe Holds Training Courses at the Front

Promotion from the Ranks

Illustrated report by Dietrich, war correspondent.

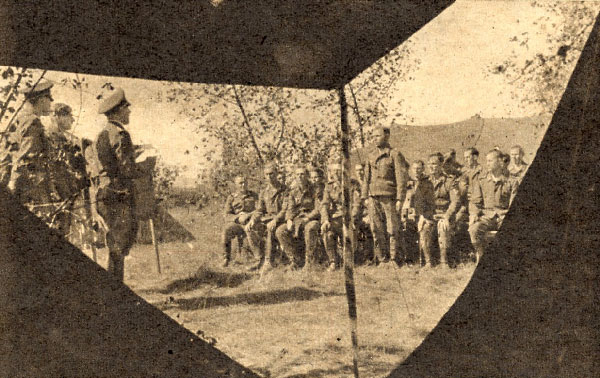

Training courses are held among the fighting formations at thc eastern front for promotion to non-commissioned officers, just as young soldiers are also trained at home.

Privates with particularly fine records are selected for these courses. The Iron Cross, First Class with front flight clasp, worn by this airman bears eloquent testimony to his gallantry.

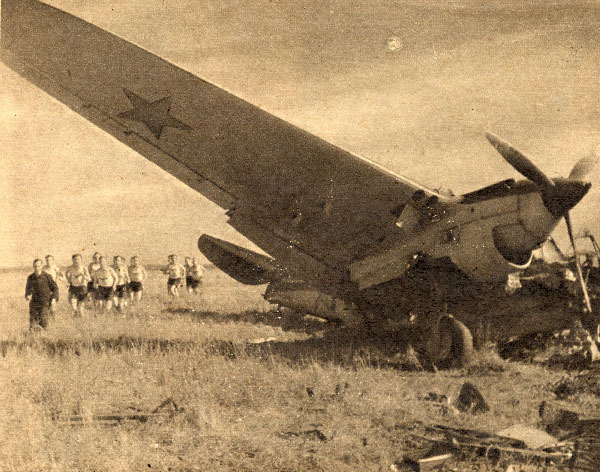

Running exercise over the wide open space of Soviet Russia past the debris of enemy planes.

After the bulletin of the German High Command has been read out, the instructor discusses the latest successes by reference to a map. The candidates follow his remarks with keen interest, because their squadrons, to which they will be returning after completion of the coursc of instruction, have been taking part in these operations.

Training courses at the front naturally do not have barracks with classrooms at their disposal and the candidates are accomodated in tents, while instruction takes place in the open air—weather permitting.

The day's duty is extensive and consists mainly of infantry' drill. The candidates are here seen marching out for drill, as the machines on the neighboring airdrome are being got reatly to take off.

Every airman must be able to handle the aircraft weapon, the machine-gun. Accuracy of fire is gained by aiming drill and shooting at butts on ground firing-ranges.

IRON RHYTHM

Aerial Warfare in the East / Pages from a Diary

By Dr. Kurt Honolka, War Correspondent

Three Airmen Win Through

Sunday, July 13

They had penetrated far into Soviet territory when the bullet of a Soviet fighter sets one of the engines of the plane on fire. All around there is nothing to be seen but an endless vista of swampy forest, stretching as far as the eye can reach; the observer seeks in vain for a suitable flat surface for a forced landing. There is just time to jettison the bombs. Corporal K. rapidly sizes up the situation, calculates the course, and says quietly: "We must march 210 degrees; we will then meet our tanks."' The machine sinks lower and lower over the forest and then thunders into the tops of the pine trees, although the pilot brakes the fall with all the skil at his command. There is a sound of crushing and bursting and ripping. The four men are flung forward. All are enveloped in smoke and flames. Three men succeed in clambering out of the blazing wreckage, but the observer is sitting quite quietly buddled up on his face. His friends drag him out, regardless of the flames and their own injuries, and carry him to safety. "Are you hurt, Otto?" asks the sergeant. But little Corporal K. gives no reply. His eyes are glazing. "Goodbye, old pal, goodbye . . ."

The three others tear themselves away. No time is to be lost. There are Soviet blockhouses quite close by, as they had just seen from the plane. They must quickly seek a hiding place in the forest. They notice for the first time that they are in a terrible plight; their faces are cut and smeared with blood, all are lame. The pilot, Sergeant K., has come off worst with a serious infusion of blood in his foot; he can just manage to drag himself along. But they must not risk being taken prisoner; there is no option, but to keep going.

The gunner, Sergeant M., takes the compass from his pilot. At least they know the course that may take them to German troops as they march past. They will owe their safety, if they are rescued, to the sangfroid and foresight of their dead comrade. By the wan dusk of the night, which in these latitudes does not become dark, they reach a clearing with a few wretched huts and a miserable patch of cultivated ground. A few hungry brats are crying in the solitude. The three men fling themselves down exhausted at the edge of the clearing and fall fast asleep.

At early dawn they set out again, hobbling painfully along through the wilderness of the ssemingly neverending swampy forest. Tortured by thirst, they soak their handkerchiefs in a pool and suck the dark colored liquid. There can be no question of food; for they have nothing with them but their pistols. The forest opens again to form a clearing, but the three men quickly fling themselves to the ground as they reach the edge. For a grodp of Soviet soldiers—there must have been about twelve of them—file silently past only a few paces off. It's a nuisance, thinks Sergeant M. to himself, that we are so done up. But they have a comrade with them who can only drag himself along by the exercise of all his will power. The others have to regulate their pace by his, helping and encouraging one another. To get on, to get on further, is the only idea animating them. They catch sight of Russian sentinels patrolling on a slight elevation. The enemy are close at hand. The second night descends with its pale semi-darkness, and the three fugitives spend it between bushes and scrub at the edge of a swamp. The night is sultry and vibrates with disquiet and the sounds of strife. At brief inter- als they can hear the familiar sound of Ju 88 bombers thundering overhead. Throughout the whole night, they can hear them on their way to their missions in hostile territory. Now and again there is a rattle of machine-guns or carbine shots resound dully. Once they could make out the shadow of a Russian Rata, as it flew over them, and then soon came the sound of anti-aircraft guns. "These are our lads. They can't be far off!"

Starting next morning is a matter of some difficulty, but they finally succeed with trouble in staggering along, their faces swollen and their feet covered with sores. The pilot, Sergeant K., is suffering acute pain in his leg. He can go no further. "Come along, Paul. Just to the next hut. We'll stop there." They continue to stumble on. Suddenly telegraph wires and a railroad appear, showing that they are at last out of the green wilderness. Are the enemy here, or friends?

The forest opens again to form a clearing. They see a group of Soviet soldiers filing past only a few paces off

They finally discover a dilapidated little hovel and their exhaustion makes them throw aii prudence to the winds. They find an old ragged Russian in the room who does not understand, a word of German. Sergeant M. and Corporal S. search the hut for food, but not a crust of bread is to be found. The garden is an untended wilderness; the whole hut is incredibly poverty stricken and filthy. There can be little doubt that they are in the U.S.S.R. In the yard they can hear the sound of children sobbing somewhere, evidently the sound comes from behind the wooden door over there . . . When the door is finally opened to their knocking, they find a woman and five children herded together on one malodorous room. By means of signs they find an explanation of the scene. The family had fled to that hiding-place out of fear of the Bolsheviks; they were hiding from the Soviet army. They breathe with relief, as they see German uniforms, and leave the hole where they had been hiding for days.

But now they must push on. The three drag themselves painfully along the railroad track. Come what may, they are tired, dog-tired. Suddenly they hear a rattling sound close at hand—that must be the caterpillar tracks of tanks. Sergeant M. runs through the wood as well as he can with his lacerated feet in the direction of the noise and at last his feverish, but glad eyes can make out that they are actually German tanks. An endless column of German tanks. Sergeant M. hurries towards them, while machine-gun barrels turn toward him silently and menacingly. "Don't shoot! Another two menare behind", he cries. An order is given, the column halts—soldiers climb out and take charge of the three bloodstained, unshaven, dusty men whose self-control gives way, now that they are safe, and a breakdown follows. Saved I Sitting and reclining in front of a pile of logs, they let the long column roll past, as it rattles by on its advance to the north-east. Buddies in field-gray wave to the three comrades in the dirty blue uniforms and hand them canteens, chocolate, and biscuits.

The last of the tanks takes them along with it

Tuesday, July 15

An order for me comes in. I have to pack up at once and report for duty to my war-correspondent company. The time has come to bid farewell to the squadron. It is no easy parting. I have been living with the bombers for three months in France and in the east ; 1 have flown with them, shared with them good billets and bad, pleasant hours and sad. Bidding farewell is no light matter.

Saturday, July 19

We start tomorrow on my new mission, travelling with a couple of cars of the Propaganda Company to the northern front to visit fighter pilots, anti-aircraft units, and observation airmen. According to the latest news from the front, extremely desperate fighting is going on in this sector. The aim is to break through the Stalin line south-east of Lake Peipus, in order to push forward in the direction of Petersburg, while the left wing blocks the land bridge north of Lake Peipus to the Gulf of Finland, so as to cut off the Soviet armies locked up in Esthonia from their connections with the east. The dry words of a General Staff officer will soon assume life and color—we will soon be seeing with our own eyes the reality of the execution of the plan and make the acquaintance of the visage of war on this front.

An army under canvas

We are now on Soviet soil. In the evening we reach the fighter formations. Two wings of the famous Trautloff fighter group are lying here, a few hundred yards from the dusty track. The slender Me 109 fighter planes are well camouflaged and cannot be made out until standing right up beside them. A gigantic mass of equipment is accomodated here in countless motor trucks and tents, ready to move at a moment's notice. The command post of the wing is a tent, the officers' mess is a tent, the whole group, from the commodore down to the most junior pilot, have been tent-dwellers for more than four weeks. That is one of the special features of this campaign in the east; a force of millions of men is living in tents. The green speckled tent square with the telescopic poles and the iron tent pegs which every soldier carries with him have long since ceased to be regarded as so much troublesome knapsack lumber. Tents have become thedwelling of the German soldier in this country, where the towns are burnt out ruins and the villages consist of dilapidated and squalid huts full of dirt, stench, and vermin. Something of the spirit of adventurous romance of the mercenaries of the good old days of yore has once again arisen in the towns of tents and bivouac fires. But it is a romance, the magic of which is drowned in the thunder of the guns, the dull rumbling of exploding bombs, and the nocturnal glare of blazing villages.

That night also one or two Soviet bombers put in an appearance. Some of them are very daring guys. Tlie anti-aircraft gunners tell us of one who attacked an anti-aircraft emplacement of this fighter airdrome just the night before and wounded a gunner with machine-gun fire. A low-level flight like that was naturally no better than suicide and the pilot was promptly shot down a few seconds later. Reckless and suicidal—these two words characterize the fact that the Russian soldier fights on other lines than we do. Their behavior has hardly anything to do with courage and bravery, as when the Soviet soldiers rather let themselves be run over by our tanks than surrender, or when they lurk in the undergrowth, although separated from the main body and hopelessly surrounded, suddenly opening fire until they have themselves been riddled with bullets. It is the fighting spirit of the warriors of Genghis Khan, which is prepared to squander human lives and holds them of less account than our carbine shells.

Wednesday, July 23

Splendid lads, the officers of this fighter wing. I have seldom seen such fine heads as at the primitive breakfast table in the mess tent. It is really a racial selection of the fittest.

"It's a pity you weren't here three days ago", says the fair-haired Oberleutnant S. to me with a smile. He is wearer of the Knighthood Cross and captain of the "Devil's Own Squadron". "You would have experienced a wild adventure. The man sitting over there had the unusual honor—but just let Leutnant W. tell you the story himself." It was really a delightful tale that he told me.

The two hundred and fiftieth down

A Me 109 fighter plane comes flitting along over a field airdrome on the north-eastern front in the first rays of the morning sun. "It's wobbling!" everyone cries, "It's wobbling! That makes up the 250!"

Three Russian Ratas had been sighted shortly after 3 o'clock that morning, flying steadily towards the south-west. Two Me 109 fighter planes immediately take off and chase after the enemy machines. Fifteen minutes later Leutnant W. is wakened from a drowse on a field-bed by the familiar notes of an engine. "That's a Rata for sure", he says to himself. Its two companions had been shot down a fewminutes previously and it is now seeking safety in flight. Leutnant W. is wideawake in an instant and it flashes through his mind that he will have to be pretty spry to get it. Meanwhile the Rata is beating it for all it is worth, the pilot is nosing down to caise the speed, and the dense ground haze rolling over meadows and forests brings it safety. The Rata vanishes.

Leutnant W. is annoyed. "Is that all I crawled out of the warm blankets for?'" he says, "Not on your life!" And so off he goes on his lonesome, crossing and dodging hither and thither over the front—but all in vain, not an enemy plane is to be seen, and he finally turns for home. Suddenly his heart leaps for joy; for over there at some 3,300 feet up are to be seen two twin-engined planes flying majestically to the southeast. Martin bombers!

Like some bird of prey he swoops on the plane at the right, whose rear gunner opens a furious fire with his machine gun. But now the Messerschmitt is firing with all its guns, two well-aimed bursts of fire and the Martin bombers flops with a trail of black smoke behind it and crashes in flames. The Me makes a rapid turn and goes for the second machine; it is ready for him and its luck is in this time. A burst of fire hits the instrument board of the German plane, smashing the instruments and missing the pilot's head by inches. That all takes place behind the Russian front. Well, there is no choice; however reluctant to do so, the pilot must turn away and see about bringing the damaged machine home. They young officer succeeds in mastering the last and most difficult part of the adventurous morning flight. He turns the damaged plane and flies home, where he lands in good trim.

The head of a red laughing fiend ornaments the arms of the squadron to which Leutnant W. belongs. And they are all young daredevils themselves, our fighter pilots, dacing and ready for a scrap at any hour of the day.

Cross-examination

Friday, July 25

We billeted ourselves in the sick and inspection rooms of a Soviet airdrome that had been occupied the day before yesterday by the advance party and that very evening we witnessed an unexpected aerial fight. Five Martin bombers were to be seen thundering over the forest on the other side of the road, some two miles off, with a swarm of Me 109 fighter planes in hot pursuit. The whole drama was over within a few seconds. Brief flashes against the pale blue sky, three times, five times, then the tracer bullets of the ma- chine-guns. Ail at once a yellow flame flashes up in the air which rapidly falls earthwards in a steep arc, suddenly expanding as it comes into contact with the dark green forest to form a mighty, dense cloud of fire and smoke. A bomber had crashed aflame. The soldiers down here watch the entrancing spectacle and shout and applaud as the scene is repeated three times. Then the ghostly visitation in the sky had vanished.

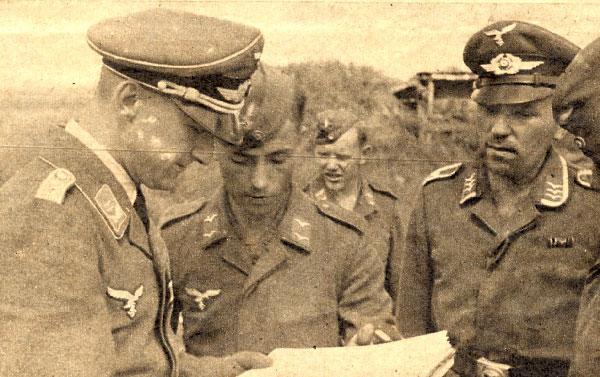

Barely an hour later some men of the labor battalion brought in two members of the crew of one of the Russian planes shot down, who had saved themselves by parachute. They were taken before the captain of the airdrome company for interrogation, and it was interesting to note their behavior. Both were officers, although their shabby uniforms might not have led one to think so. The elder of the two, a tall, dark- skinned man of about 27, was Oberleutnant, while the other was a Leutnant, slim and blond. There was nothing much to be got out of the Oberleutnant. He professed complete ignorance, and even became fresh and gave ironical replies when he saw that he was being treated correctly and not subjected, as he had probably expected, to a little judicious pressure in the way of torture. The fairhaired subaltern might have been 22 or thereabouts. He was on the verge of tears and begged frequently not to be shot: he would tell us everything. As a matter of fact he gave quite a lot of interesting information without being intimidated by the grim looks of the Oberleutnant.

Timoshenko Armies under a Hail of Steel

Night of Terror on the Roads round Vyazma

Retreating Enemy Columns Attacked with Bombs and Aircraft Weapons

By Martin Winkelmann, War Correspondent

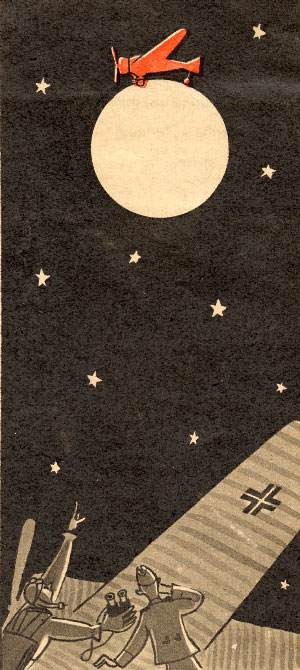

Never shall we forget that night when the enormous net about Vyazma was drawn tight, when the town itself went up in flames, and the disorderly flight of a medley of columns found a sudden end beneath the hail of steel from our bombers on the roads round that town. Unforgettable were the blazing pillars of flame that we flew over at a low height, the smoldering stench of which filled our machines; never would we be able to forget the frenzy of panic among the Soviet vehicles, as we swooped deep down with our "Bruno-Richard'' like some fiery dragon to drop our bombs into the chaos, cutting swathes with our machine guns as we swept over the road. The fate of Timoshenko's fleeing armies was sealed within a brief half hour, and the drama of Vyazma came to a close.

Confused heaps of motor vehicles of every description driven together pell-mell, tanks lying across the road, and blazing motor trucks blocked and choked the road for all other traffic. The flight had been frustrated. That very same night the tip of the tanks pushed forward to the north of Vyazma and completed the encircling manoeuvre announced by the bulletin of the German Supreme Command. The roads and railroads about Vyazma had been the objective of the last few days. The town still defended itself with stubborn fury against the German advance, dozens of search-lights still flared up at our approach and anti-aircraft guns of every calibre still opened fire on us. But we noticed on our nocturnal flights that the front was beginning to show signs of movement and losing its rigidity as the German advance began on October 2 as willed by the Fuhrer and proceeded further and further, more rapidly than we were able to mark on the maps at the command post of our bomber wing. More and more burning villages and peasants' huts lined our flying route and the sky behind Smolensk was red with the glare of fires.

The same fierce light points us today once more the way to the front. The well-rounded disk of the full moon gleams brightly in the sky, giving us a clear view far over the countryside. Fires are to be seen to the north, to the south, and to the east. Some have just started and are blazing brightly, while the darker patches of flame show that a conflagration is smoldering to extinction with convulsive movements. At first there are but three or four, then their number grows—now to ten, to twenty, now the whole front is one huge blaze the more closely we approach. Shells burst in between and tracer bullets whizz over the roads and rivers. We are already above the road that runs from Smolensk to Moscow, immediately to the north of Vyazma. We really intended to avoid that town, in view of our experience of the last few days, but it becomes clearer minute by minute that it has already received the coup de grace and no longer thinks of defense. At a height of only a few hundred feet we fly over a sea of wildly darting flames, crashing houses, and whole streets of ruins, right into the reddish black clouds of smoke that fill turret and dustbin with the acrid stench of charring wood. One conflagration is raging beside the other, as far as the eye can reach.

HENSCHEL STUKA. HENSCHEL FLUGZEUG - WERKE. A.G. SCHONEFELD / BERLIN [Advertising - AWW].

Then back again to the road. A fever seems to seize the whole machine. Not a word is spoken and yet each of us wants to utter the same words, to shout them with the whole power of his lungs; for the beaten enemy down there is evacuating the burning town and fleeing for dear life. Timoshenko's armies are trying in wild confusion to escape the steel encirclement by the German forces. Groups of twenty v or thirty vehicles, then single vehicles, tanks, motor trucks, motor cars, armored reconnaissance cars—all hurrying and scurrying with frantic haste along the broad white ribbon of the road to the east. The crew understand what is to come without losing many words. The pilot is already nosing the He 111 bomber lower and lower, his eye glued to the white ribbon that stretches eastwards straight as an arrow. The first bombs drop right into a jumbled welter of at least thirty vehicles of every description and detonate so that we in the dust-bin imagine for a moment that we ourselves are flying into space. "Wonderful! Wonderful!" We find no other word to express our feelings. Then three machine-guns and a cannon take a hand, spraying bursts of fire on tanks and motor trucks, so that oblique strikers are scattered far and wide in the neighborhood into the air, almost reaching our machine, as it thunders over the columns at a very low level. Salvoes are fired at us from a place in front of us, but the pilot banks away from the locality so steeply, as to make us catch our breath, and back to the road. The same strafe is repeated a second time. Bombs and bursts of fire sweep into and between the columns, which are already noticeable in disorder and are trying to escape in all directions. Over there a bomb seems to have dropped right among them. A motor truck lies across the road and other vehicles have been driven into the ghastly mix-up. But we catch no more than a glimpse of all that as we roar past; for our weapons demand our whole attention. Breeches and ban-els are glowing hot. But we should worry! Tack-tack-tack and peng-peng-peng go machine-guns and cannon; the only language that goes now!

Again and yet again we fly along the road. All our bombs have long since found their billet and only the weapons still spew fire and destruction on the fleeing foe. By the fourth attack everything has come to a standstill. The road is inextricably blocked. Only an occasional shot is fired by way of defense. The Soviet troops are so panicstricken as even to overlook the fact that the low-flying plane presents an excellent target. There is only one dangerous moment, as a double- barrelled machine-gun set up in the middle of the

road opens fire on us. It is too late to make a detour and the bullets whang into the machine. The pilot noses further down and then we are over it and away. Fortunately, no one was hurt and the few scratches do no harm to the good old Heinkel 11 plane.

We call a halt only after the last drum of machine-gun ammunition has been shot off and the last cannon magazine is lying in the dust-bin. Then we lay our course for home. Great piles of empty drums and magazines lie around us, leaving barely room for ourselves. Perspiration streams from beneath the flying helmets. But we have the proud certainty of knowing that the flight of the Russian armies has been checked and that they are now completely surrounded. And we were privileged to be able to help a little.

Friendship between German and Romanian Airmen

Germany Builds up the Romanian Air Force

By Wilh. Spiegel, War Correspondent

One often heard before the present war of the great family of European airmen and the esprit de corps that animated them and was constantly brought out at competitions, international meetings, and on similar occasions. Romanian airmen were also to be found among that band of airmen united by a camaraderie that had overcome the antagonisms of the Great War and one of their number, Prince Bibesco, whose death occurred not long ago, was esteemed and admired all over Europe, more particularly in Germany, as President of the International Association of Sport Flyers of the Federation aeronautique internationale.

There is thus perhaps little need to Ipok for a special explanation of the fact that German airmen are everywhere welcomed with extraordinary friendliness in Romania, wherever Romanian airmen meet. But there is still another reason, apart even from the common anti-Bolshevist front existing since June 22, and I was easily able to find the reason for that still closer alliance when I had occasion to visit a number of Romanian airdromes. It is the decisive work that Germany has done in building up the Romanian air force and is now making itself felt in the common struggle against Bolshevism.

Romania had already stretched out feelers all over the world, before it took up closer cooperation with Germany, and had purchased airplanes in every country with an aircraft industry, in order to collect experience. That is the reason why the scene on a Romanian airdrome even today still recalls the great international aviation exhibitions in the capitals of Europe. Types of aircraft and aero-engines from all over the world are to be found there and the judgement of Romanian airmen, which is today unequivocally in favor of German aviation, is for that reason all the more to be valued. When the commander of a bomber squadron equipped with He 111 planes tells me that he is proud to lead the best bomber squadron of the Romanian air force, that testimony is an expression of opinion hardly to be surpassed. That same commander and a large number of other officers received their training as bomber pilots wholly or partly in Germany. Some Genuine esprit de corps reigns wherever German and Romanian airmen meet of them wear with pride the German flyer's badge and remember their German instructors, from whom they parted as the best of comrades, with pleasure and gratitude.

Genuine esprit de corps reigns wherever German and Romanian airmen meet.

The judgment of the Romanian officers is strengthened by a number of proud successes which the bomber squadron had gained in hundreds of raids on railroad depots, airdromes, lines of communication and supplies, bridges, and fortifications, as well as in low-flying attacks on assemblies of enemy troops. Of course there were also casualties to be deplored, but the dependable design of the He 111 machines often enabled them, although badly hit, to bring their crews safely home, often with only one engine.

" . . then it burst into flames and broke up." A Rumanian flying officer describes to his German comrades the details of an air fight with a Sovier fighter plane.

After bidding farewell to the bomber pilots, I visited a fighter group, part of which was equipped with our Me 109 machines, and here again I met pilots who proudly bear the German flyer's badge. They had been trained by German instructors in the advanced art of the fighter pilot and have proved in many a successful aerial combat the value of that training and the merits of the German fighter plane. Romanian fighter pilots must even overcome a certain national pride, which might perhaps be better termed local patriotism, in praising our Messerschmitt planes, because a Romanian-built fighter plane of quite respectable design and performance is also at their disposal. Romanian pilots have but one wish in connection with our Me 109 plane and that is—"If we only had a lot more of them!"

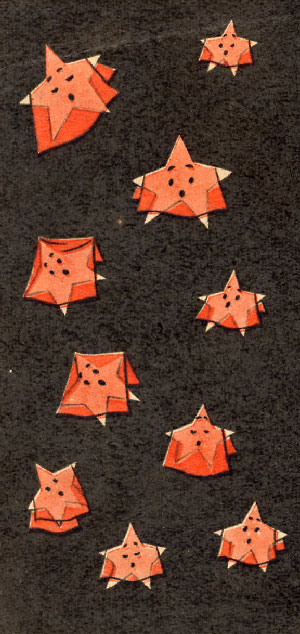

The Stars Are Gleaming in the Sky

Whimsicalities from the front

By WERNER KRUSE

"Say, you guys, don't forget to black out! The Germans fire on every damned star they see!"

"Hell and all! I never saw so many stars together in all my time!"

"Quick, Mike, wish V yourself something. You won't see so many shooting stars in a hurry again!"

"T'm going to write underneath my photo to Maggie, "I'll fetch you the stars from heaven!'"

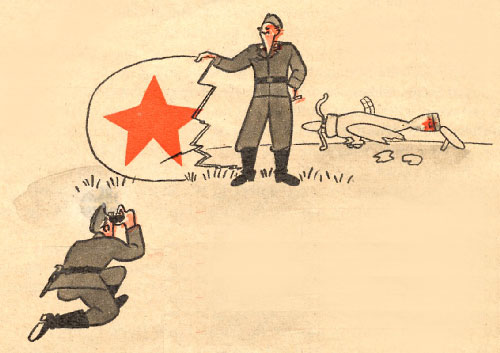

"There you are, you old sceptic. Look for yourself! I compelled him to make an emergency landing there!"