Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

ABOUT HITLER'S FATE AND HIS ROLE IN THE LAST FIGHT FOR BERLIN

BY THE GENERAL OF ARTILLERY HELMUTH WEIDLING

Biography

Helmut Weidling was born on November 2, 1891, in Halberstadt, Saxony, in the family of a physician.

Weidling joined the German Army in 1911 and started the First World War as an air observer. In December 1914 he was transferred to an airship squadron where he served as a navigator on LZ Sachsen, LZ 85 and LZ 97 airships. In 1915 he was promoted to Oberleutnant. From June 1916 he commanded LZ 97 and LZ 113 airships. In May 1917 Weidling was appointed Chief Adjutant of Military Aeronautics, and later he became Chief Adjutant of a Commander of the Imperial German Air Force.

In 1919, after the abolition of the Air Force, Weidling served in artillery troops. in 1922 he was promoted to Captain, in 1933 to Major, in October 1935 to Lieutenant Colonel, and on March 1938 to Colonel.

In the war against Poland in 1939, Weidling commanded an artillery regiment; in the war against France in 1940, he commanded artillery of the 9th Army Corps, then of the 4th Army Corps. He participated in the war in the Balkans. On the Eastern Front, he served as artillery commander of the 41st Tank Corps until the end of December 1941. From the end of December 1941 to October 1943, he served as a commander of the 86th Infantry Division. On October 20, 1943, he was promoted to the commander of the 41st Tank Corps and served in this capacity until Corps’ destruction at the beginning of April 1945.

On April 10, 1945, Weidling assumed command of the 56th Tank Corps. On April 23, Hitler, enraged by a false report about 56th Corps transfer without permission from HQ, ordered Weidling’s execution. Learning about this order, Weidling arrived at the headquarters and was able to arrange an audience with Hitler, after which the execution order was canceled, and Weidling was appointed as a commander of the Berlin Defense, replacing lieutenant colonel Erich Beerenfenger. Weidling tried to organize the city’s defense against overwhelming odds, but eventually lost the battle for Berlin. On May 2, 1945, he signed the capitulation of the German troops and surrendered with the remnants of the Berlin’s garrison.

After the end of the Second World War Weidling was incarcerated in Butyrskaya and Lefortovo prisons in Moscow, and then in Vladimir Central prison. On February 27, 1952, the military tribunal of the Moscow Military District sentenced him to 25 years in prison on the charges of war crimes. According to the accusations, in March 1944 to “clean up” the rear areas of his 41st Tank Corps, Weidling ordered to drive thousands of local and evacuated civilians to the concentration camps near Ozarichi, Belorussia, most of them died there from typhus and inhuman conditions of the detention.

During his interrogation, in December 1945, Weidling was suggested to write his thoughts about Hitler’s fate and Fuhrer’s role in the fight for Berlin.

Helmut Weidling died on November 17, 1955, from a heart attack in Vladimir Central Prison. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the prison cemetery.

General of Artillery Helmuth Weidling

ABOUT HITLER'S FATE AND HIS ROLE IN THE LAST FIGHT FOR BERLIN

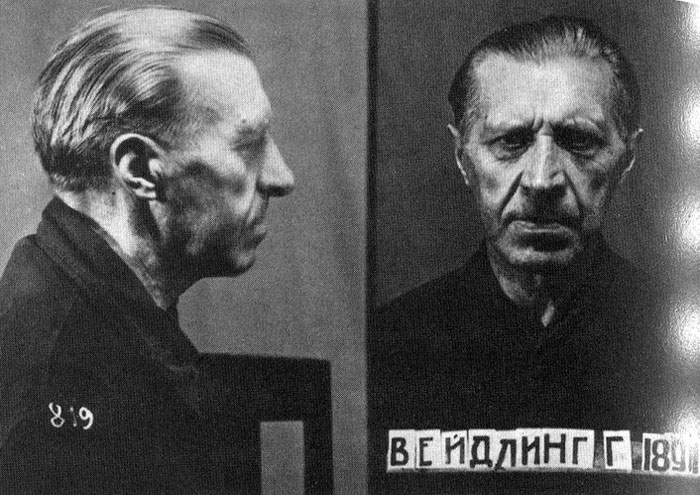

Weidling during the interrogation

I met the Führer of Germany and the Commander-in-Chief of the German Armed Forces for the first time on April 13, 1944. I was summoned to Hitler in Berghof near Berchtesgaden with 12 other senior officers and generals to accept the military award of the Oak Leaves of the Knight's Cross.

Hitler’s chief adjutant, General of Infantry Schmundt, summoned us all to Hitler’s large office and carefully instructed us that we should tell Hitler only our name, rank and position, adding that if Hitler wants to know more about us, he will ask us additional questions.

Hitler entered the room. A painful pallor covered his face, and he was swollen and hunched. Each of us introduced himself as instructed. Presenting us with the awards, Hitler limited himself to shaking hands with a recipient without uttering a single word. As an exception, he asked Lieutenant General Hauser, who came in on the crutches, about his physical condition. After the award ceremony, we all sat down at a large round table in his office and Hitler gave us a half-hour speech, which was spoken in a quiet, monotonous voice.

In the first part of his speech, Hitler touched upon the evolution of the weaponry during this war and the tactics that were developed accordingly by both sides. At the same time, Hitler peppered his speech with various numerical data on a caliber, range, armor thickness, and so on. It was obvious, that Hitler has quite an exceptional memory. However, it seemed to me, that the issues he raised there were of the secondary importance.

In the second part of his speech, he touched on political events. "The cooperation of the Anglo-Americans and the Russians," said Hitler, "cannot be successful, since the concepts of communism and capitalism are not compatible." Based on this situation, Hitler, as was evident from his speech, hoping for a favorable outcome of the war. Having finished his speech, Hitler stood up, shook hands with each of us, and we were dismissed.

I left Berghof dissatisfied and disappointed. The conversation that took place after this meeting with the general of artillery Martinek characterizes this mood.

We asked ourselves the question of why it was necessary to take us from the front to Berchtesgaden. Most of the recipients expected that Hitler would use this occasion to let everyone share his thoughts on past battles. After all, these were the most experienced officers, summoned straight from the front. A real commander should have a keen interest in their needs and demands.

“You see, here we have an idea of the invisible wall that encloses Hitler,” Martinek said. “Yes,” I replied, “Hitler cannot and does not want to hear what reality looks like. Camarilla took care of that. Otherwise, General Schmundt would not have lectured us about what we should talk about during the meeting with Hitler.”

"For the same obvious reason," Martinek put in, "Hitler stopped his trips to the front in the last year and a half because some sincere person could have told Hitler that we would never win a war with such military leadership."

I fully agreed with Martinek and added: “I am bitterly disappointed in Hitler’s behavior. He hasn’t said anything about hard fighting, which, most likely, we will see later this year. We heard enough lecturing from him, but all of this can hardly be applied practically. How will all this end?”

I had a chance to meet with Hitler a year later, under completely different circumstances. Russian spring offensive of 1945 on the Oder began on April 16. The 56th Tank Corps, which I commanded back then, was in the Seelow–Buckow area, west of Kustrin, on the way of the main Russian offensive. Shortly after the start of the Russian offensive, as a result of exceptionally heavy fighting, there were breakthroughs on the right and left flanks of the sector I defended, as well as in the rear of the corps. Communications with two adjacent corps and with the army were severed. But the corps was still able to conduct defensive battles and retreat westward to the outer ring of Berlin’s defenses.

On April 21, I sent Lieutenant-General Voigtsberger, the former commander of the “Berlin” Division, to establish contact with the 9th Army. Two days later, Voigtsberger returned from the Army’s HQ and with the great excitement reported the following. The army received a message that, allegedly, I, with my corps headquarters, and without HQ’s permission, had moved to Deberitz, west of Berlin. In this regard, Hitler issued an order about my arrest and execution. Voigtsberger pointed out the improbability of such redeployment. The combat order he brought from the Army to the 56th Tank Corps said that it should contact the left flank of his neighbor to the right.

I was left in the dark regarding my situation at first, but the order we received made our hearts beat faster because the very thought about upcoming fights in the destroyed city was unbearable.

I, together with the chief of staff, Colonel Dufing, immediately began to prepare an order to regroup the corps on the night of April 23-24. During this work, the chief of staff of the fortified area of Berlin, Colonel Refior, telephoned General Krebs's order to send the staff officer of the 56th tank corps with the map of the units’ location to the Reich Chancellery. For these two reasons, I decided to go to the Reich Chancellery myself. First, I wanted to find out why the order of arrest and execution had been issued in the first place. Secondly, I intended, if possible, to ensure that the corps will not participate in the battles in the ruined city.

At 6 pm, accompanied by the head of department 1A of the corps headquarters, Major Knapp, I arrived at the Reich Chancellery. From the sidewalk of Fossstrasse, the staircase led to an underground city, which was built between Wilhelmstrasse and Hermann Goeringstrasse. One can get an idea of the magnitude of this refuge if one considers that during the intensified raids on Berlin, being conducted every evening, Hitler’s guests were 4–5 thousand Berlin’s kids.

We were immediately led to the so-called Adjutant Bunker. I was received by the Chief of the German General Staff, General of Infantry Krebs and Hitler’s adjutant General of Infantry Burgdorf. The meeting was somewhat cold, even though I knew Krebs well from the time of Reichswehr and later when he was the Chief of Staff of the 9th Army and the Group Army Center.

In the course of the conversation that followed, I was able to convince both generals without difficulty that if they consider the military situation of the last days, I had not intended, and there was no point and expediency to redeploy to Deberitz. They were forced to admit that they took some insignificant rumor for the fact and now, after my explanation, they regret their gullibility. Nevertheless, it turned out that I had been removed from my post, and nobody hasn’t said a word to me about this.

Speaking about the situation in East Berlin, Krebs told me that he was worried about the deep breakthrough of the Russian units. They wanted to discuss with me what countermeasures might follow from the 56th Panzer Corps. When I brought to their attention the combat orders of the corps received from the 9th Army, Krebs exclaimed: “Impossible, absolutely impossible! I will immediately report this to the Führer.” With these words, Krebs left me, followed by Burgdorf, his shadow.

I instructed Major Knapp, who accompanied me, to notify my Chief of Staff by phone that the corps might be used this night east of Berlin. During this phone conversation, the Chief of Staff said that a telegram had been received from the Office of the Army Staff, signed by Burgdorf, which said: “The General of Artillery Weidling has been transferred to the OKH reserve. Lieutenant General Burmeester, commander of the 25th Panzer Division is appointed the commander of the 56th Tank Corps".

I was outraged. Indeed, it was only by chance that I managed to rehabilitate myself. But how many generals have recently been sent away never heard about again only because they could not dispel the widespread rumors, related to them! While Krebs and Burgdorf were absent, I received a brief orientation on the situation in Berlin from one of the Krebs’ officers.

Hitler, with a small number of his assistants, remains in Berlin to lead the defense of the capital personally. The flight of state authorities from Berlin began on April 16th, and the road to Munich was called now the "Reich Refugees Road."

OKV and OKH were transformed into two operational headquarters; North Headquarters, headed by Field Marshal Keitel, and South Headquarters, under Field Marshal Kesselring. Colonel-General Jodl was sent to him as a Chief of Staff. The reorganization took place so quickly and thoughtlessly that both headquarters took all the radio stations from Berlin with them. The German command in Berlin could communicate only using the remaining SS radio stations associated with the station at the Himmler’s headquarters.

I was briefly told about the following interesting event. On April 23, Goering sent a telegram from Berchtesgaden, which fell like a bomb on the Reich Chancellery. Goering demanded from Hitler the transfer of executive state power to himself since Hitler was unable to carry out government affairs while staying in Berlin. Demanding that, Goering referred to Hitler's speech in the Reichstag on September 1, 1939, where Goering was named as Hitler’s successor.

Once Krebs and Burgdorf returned from their meeting with Hitler. Krebs told me: “You must immediately report to the Führer the situation of your corps. The order to the 9th Army has been canceled. The corps will be used east of Berlin this night.” Then I vented my indignation and declared that the position of the corps should be reported by its commander, General Burmeister. Together, the two generals barely managed to calm me down, and they said that Hitler decided, of course, to leave me at the head of the corps.

Even though I went to the Fuhrer’s bunker accompanied by both generals, my papers were checked three times most thoroughly. Finally, the Untersturmfuhrer SS took my pistol.

From the so-called Kollenhoff, the underground passage led deeper and deeper to the underground labyrinth. Through a small kitchen, we entered the room with dining officers. Then we went down the floor below and entered Fuhrer’s reception room.

There were many people in gray and brown uniforms. Walking through the reception room, I recognized only the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ribbentrop. Then the door opened, and I appeared before Adolf Hitler.

He sat in a chair in front of a large table in a relatively small room. When I arrived, Adolf Hitler stood up with noticeable tension and leaned with both hands on the table. His left leg shook continuously. Two feverish eyes gazed at me from the swollen face. The smile on his face was replaced by a frozen mask. He extended his right hand to me. Both hands also shook like the left leg. “Do I know you?” He asked. I replied that a year ago he rewarded me with the Oak Leaves. Hitler said that he easily remembers names, but not faces. After this greeting, Hitler sank back into his chair.

I reported the corps situation and declared that the corps is in the middle of the redeployment to the south-east. If the order to return the corps will be issued, a terrible mess will occur tomorrow morning.

However, after Hitler and Krebs had a short conversation, the order to move the corps to the eastern section of Berlin was re-confirmed.

In the end, Hitler started a lengthy conversation, in tune with his criminal amateurishness, about an operational plan to free Berlin from the blockade. He spoke in a quiet voice with long pauses, often repeated and unexpectedly becoming interested in the secondary issues, which for some reason were discussed in great detail.

Hitler’s "Operational Combat Plan" was as follows. The 12th Shock Army under command of Lieutenant-General Wenck is advancing from the Brandenburg area through Potsdam to the south-western part of Berlin. At the same time, the 9th Army receives an order to break away from the enemy on the Oder line and conduct an offensive in the south-eastern part of Berlin. As a result of the interaction of both armies, the Russian forces will be destroyed south of Berlin.

To create the maneuver capabilities of the 12th Shock Army and the 9th Army, the following German forces will be sent against the Russians to the northern part of Berlin: the 7th Panzer Division from Nauen area and the Kampfgruppen SS Steiner from the area south of Fürstenberg.

Later, i.e. as soon as the Russian forces are destroyed south of Berlin, it is planned, through the interaction of all four attacking groups, to destroy also the Russian forces north of Berlin. When Hitler finished his presentation, it seemed to me that everything he said, I heard as in a nightmarish sleep.

For several days already, I continuously participated in major battles and knew only one thing that if a miracle would not happen in the last hour, in a few days a final catastrophe should occur.

Ammunition was available in limited quantities, there was almost no fuel, and most importantly, the troops were fighting without the will to resist, since they have not believed in victory and the expediency of their resistance.

Is a miracle possible? Was Wenck’s Shock Army a reserve of Germany, about which Goebbels had chatted so much in his propaganda in recent weeks? Or was it only dreaming of a fanatic who has no idea about reality?

Shocked by the appearance of a human ruin, which stands at the head of Germany and, being under a strong negative impression of the amateurishness that reigned in the headquarters, I left the Führer's office. When I left, Hitler stood up with noticeable difficulty and gave me his hand. Not a word was said about the order for my arrest, execution, and dismissal from the post. In the adjutants’ shelter, Krebs explained to me on the map of the city of Berlin the order, which had been received by my corps. I had to take over the four Berlin defense areas in the eastern and southern sectors from the existing nine. The remaining five sectors remained in the hands of the commander of the defensive area. My corps were to report directly to Hitler.

I did not fail to notice to General Krebs: “Thus, in fact, Hitler is the commander of the Berlin defenses!” And then I asked him a question: “Do you think that Hitler’s operational plan envisages relief of Berlin’s blockade?” Hitler, for example, gives the 9th Army both defensive and offensive tasks. Do you all here have an idea of the state of the army at present? The corps on the left flank has been already completely broken; its pitiful remnants were included in the Army Group Vistula. Hitler took over my corps, with its heavily battered five divisions. Regarding the neighbor on the right, I know only that it was fighting as fiercely as we did, and is, if not in the same, then in a worse condition. There cannot be a very strong 9th army either. Despite this, the army, with the stubborn and strong pressure of the Russian units, should be withdrawn from the Oder, and participate in the battles in the southern sector of Berlin. You know, Krebs, I can't follow Hitler’s thoughts.”

To all of this Krebs responded with only empty phrases. Meanwhile, I issued a battle order for my divisions and chose the Tempelhof airfield’s administrative building as a command post. At about 10 pm I left the office and went to visit commanders of the defense sectors again subordinated to me to get an orientation on the situation on the spot.

The picture from the conversation with the commanders of the defense sectors looked like as follows. Berlin was defended not by close-knit troops, but by the casual collection of the hastily consolidated headquarters and formations. They got suitable officers as commanders from somewhere. These commanders were supposed to form their headquarters in the first place. There were no means of communication.

The infantry consisted of the "Volkssturm" battalions, artillery formations and units of "Hitler Youth". For the anti-tank defense, they have only anti-tank grenades (panzerfausts). Artillery was equipped only with captured weapons. There was no single command of the artillery. Anti-aircraft batteries, which were controlled centrally, were the backbone of the defense. But, since there were few towing vehicles, the unmovable batteries were only conditionally suitable for the ground battles.

Orders were confused. In addition to the military chain of command, orders at the defense sectors were issued by many party leaders, for example, by the commissioner of defense, the deputy gauleiter, etc.

Most of all, I was shocked by the fate of the civilian population, to the sufferings of which Hitler was not paying even the slightest attention. It was easy for every far-sighted person to imagine what a terrible drama will be unfolding soon.

Late in the evening of April 24th, my chief of staff arrived at the command post of the corps and informed me that the night movements of the corps proceeded mainly according to the plan. Soon after that, I was again summoned to the Reich Chancellery. I arrived there around midnight.

Krebs told me the following: “Because of the impression you made yesterday on the Fuhrer, he appoints you as a commander of the Berlin fortified area. Go immediately to the Hohenzollerndamm Fortified Command Post and inform me of taking over your command.”

I could only answer: "It would be better for Hitler to uphold the order for my execution, and then at least I would escape this role."

However, the true reason for my appointment was, of course, the impression I made on Hitler. The first commander of the fortified area, Lieutenant-General Reiman, after a collision with Berlin’s Defense Commissioner Goebbels, was dismissed on April 24 from his post. His successor was the head of the headquarters of the National Socialist Education Department under the OKH, Colonel Kaether, who received the rank of lieutenant-general. Because Kaether did not have enough training for this leadership position, and I was the only commander of the military units at hand, this task was assigned to me.

Receiving the command of the defense area, I clearly understood that the real commander was the Commissioner of the Fortified District of Berlin Dr. Goebbels and his retinue. The headquarters of the fortified area was used mainly as an information bureau (in connection with the confused orders), so this greatly interfered with the military leadership of defense.

I did not get an accurate idea of the strength of the defense forces either when I received a defense area or later. Now I think they were equal to 80-100 thousand people. According to their training, armament, and composition, these troops were not able to defend the city of one million population against the modern army.

In mid-April thirty of the well-armed battalions of the Volkssturm were formed in Berlin and assigned to the 9th Army. The former commander, Lieutenant-General Reiman, protested this military nonsense, for which, as already mentioned, he was removed from his command.

It took me half of the day to familiarize myself with this more than just a difficult area on April 24th. Only at about 7 pm, I was able to inform Krebs that I assumed the command of the fortified area. On April 25, I spent most of the day on the road to see for myself if I would be able to defend my sector. I managed to learn some interesting details. For example, no measures were taken to evacuate the central areas of the city, which could become a battlefield at any time. The civilian population was on its own.

None of the bridges was prepared for the demolition. Goebbels commissioned this task to Schpur organization because it was thought that if the detonation of the bridges was relegated to military units, the damage could be also inflicted on surrounding private property. It turned out that all materials, prepared for the bridges’ destruction, as well as explosives prepared for this task, were removed from Berlin during the evacuation of the Schpur institutions.

In the evening I was invited to the Reich Chancellery to discuss the situation. At 21 o'clock I came to Krebs. Shortly before that, Colonel-General of the Luftwaffe Ritter von Greim, who flew to Berlin with a female pilot Hannah Reitsch, and was wounded in the leg while landing, arrived on a stretcher to the Reich Chancellery. Hitler appointed Ritter von Greim commander-in-chief of the German Air Force and made him Field marshal. Goering was relieved of this command.

Before the meeting, I saw Hannah Reitsch several times, once holding the arm of Mrs. Goebbels. The rest of the time she was in Hitler’s private quarters. I heard that later same night Hannah Reitsch flew Field Marshal Greim out of Berlin.

In the reception area of the Fuhrer’s HQ gathered almost all his staff. I was introduced to Goebbels, who greeted me with the utmost courtesy. His appearance looks like as inspired by Mephistopheles. Goebbels adjutant, Secretary of State Nauman was tall, slim, but otherwise looked like a portrait of his master. Reichsleiter Bormann, as I was later told in the Reich Chancellery, was Hitler’s evil genius. With his close friend Burgdorf, he indulged in earthly pleasures, in which the main role was played by brandy and port wine. Ambassador Hevel was hiding in a corner, and I got the impression that he had renounced everything. I have not seen Ribbentrop again; I was told that he had left Berlin.

The assistant to the gauleiter of Berlin, Dr. Schach, was almost crawling in front of his master Goebbels. The head of the German Youth Axman looked modest and reserved. Himmler’s liaison officer, Gruppenführer Fegelein, was an arrogant SS leader, self-important and convinced of his abilities. Also, there were Hitler's adjutants: Major Johanmeer from the Army, Colonel Below from Luftwaffe, and Sturmbanhfurer Günsche from SS troops. Rear Admiral Foss represented the Navy.

When Krebs showed up with the operational map, we all entered the Führer's office. Hitler greeted me by shaking my hand. Goebbels immediately took the place opposite Hitler against the wall, where he usually sat during all the meetings. All the others casually settled down in the office.

Krebs stood opposite Hitler, then Burgdorf and Bormann, to the left I was ready for the report. I had to try to force myself not to look at Hitler’s figure lowered into a chair, his arms and legs constantly shaking.

I began my report with the assessment of the enemy. As a visual material, I prepared a large schematic map with the designation of the enemy’s forces. Hitler showed a keen interest in this map. During the report, he asked Krebs several times if the data on the power of the adversary I quoted was true. Krebs confirmed my data every time.

Then I reported the situation of our troops. Except for two deep breakthroughs near Spandau, and in the northern part of Berlin, we still managed to keep the main front line. Along the way, I touched the situation about Berlin’s defense in connection with the movement of my corps. Hitler, however, made me tell more about it.

Referring also to the position of the German population, I immediately noticed that I touched an area that was alien to all. Goebbels became worried, looked at me intensely and took the floor, without asking Hitler's permission.

Everything, according to Goebbels, of course, was in the order of which his deputy reported to him from time to time. I felt insecure and had to suppress my indignation. At the end of my speech, I pointed to the great danger that threatened the entire supply. All supply warehouses were near the outer city limits, and they were about to be captured. Goebbels intended to intervene again, but then Krebs spoke and began to report on the general situation.

It became clear to me how this camarilla related to each other and everything unpleasant for them was sabotaged. Hitler’s active role was over. Physically and a mentally broken man was now only a tool in the hands of the camarilla.

The following moments remained in my memory from the Krebs report on April 25, 1945. Krebs said: “1. The 9th Army reported that it set off on the march in the direction of Zukenwald, i.e. in a westerly direction."

Hitler knocked excitedly on the table with three pencils, which he constantly held in his left hand, and which served him as a device to calm his trembling hands.

Did he see his “Operational Plan” for the liberation of Berlin’s blockade destroyed? Krebs, however, was able to calm Hitler down, even though it was clear to every far-sighted person that the 9th Army, after withdrawing the 56th tank corps, was not able to attack large Russian forces.

The willingness of the 9th Army consisted, of course, in avoiding encirclement and connecting with the 12th Shock Army of General Wenck, and Krebs reported: “2. General Wenck’s 12th Shock Army launched an offensive with 3 and a half divisions to liberate Berlin from the blockade.” These were the only reserves of Germany!

3. “Wide and deep breakthroughs of the Russian units in the Army Group Vistula will harm the defense of Berlin.”

Meanwhile, time was already 1 am. After the meeting, everyone, including the three secretaries, took part in a casual conversation. When I took a closer look, I was able to recognize more people.

On April 26, the situation of Berlin’s defenders became even more critical. There were deep penetrations in all areas. Krebs called almost every hour and tried to present the general position of Berlin as favorable as possible. First, his information was that the 12th Shock Army was moving forward and that its combat patrols were already approaching Potsdam. Despite repeated requests, Krebs did not give any answer about the northern group, the offensive of which was so desirable. These two groups did not even communicate with each other.

Another episode characterizing the behavior of the camarilla should also be mentioned. Goebbels called me late in the evening. In the politest tone, he asked me to let one of the commanders of the sub-sectors from northern Berlin, Lieutenant Colonel Beerenfenger, go to the Riech Chancellery for several hours.

Before the arrival of my corps, Beerenfenger was an independent commander of the defense sector, and then he became the subsector’s commander. Being in the past the leader of the “Hitler Youth”, he was a fanatical supporter of Hitler and well known to Goebbels. Affected in his vanity, he turned to Goebbels.

Approximately 2-3 hours after talking with Goebbels, General Burgdorf also called and informed me that Lieutenant Colonel Beerenfenger was promoted to Major General and Hitler expressed a desire for General Beerenfenger to be appointed as a commander of an independent sector. I started to think that Hitler’s HQ had become the home of the insane.

I informed Krebs daily about the situation. I was relieved of the daily evening discussions of the strategic situation in the Reich Chancellery in connection with my heavy workload.

On April 27, the enemy’s ring closed around Berlin, and the city was surrounded. In a concentrated offensive, Russian tank and rifle divisions were coming closer and closer to the center of the city. In these terrible April days, the civilian population looked with horror at how, during these fierce battles, everything that was saved from the Anglo-American bombings became destroyed. The population huddled in bomb shelters and the subway like cattle. Their lives had no more meaning for Hitler. No light, no gas, no water!

The worst was the situation in the hospitals. Professor Sauerbruch, in his letter to the commandant of Berlin, drew the terrible fate of the wounded. Being an old front-line soldier, I know how cruel modern warfare is. However, what Berlin experienced surpasses everything. Early in the morning our command post at Hohenzollerndamm was fired upon and we had to move to Benderblock.

On the evening of April 27, it became clear to me that there are only two possibilities: surrender or breakthrough. Further continuation of the struggle in Berlin meant a crime. In the next discussion of the situation in the Reich Chancellery, my task was to describe to Hitler all the futility of further struggle and get his agreement on Berlin’s surrender.

At 10 pm on April 27, 1945, a discussion of the situation took place in Hitler's office. I began by outlining the enemy’s strategic situation. According to the intelligence of my corps, the Russian tank army operating in the southern part of Berlin was replaced by the Rifle Army. It was possible to assume that the Russian command moved this tank army towards the 12th army. After the first successes, General Wenck waged heavy defensive battles southwest of Potsdam. Berlin was surrounded, and no diversion of forces was felt with the help of four advancing groups. One cannot longer count on the liberation of Berlin from the blockade.

In this regard, I pointed to the great danger that we faced partly because of German propaganda. Until recently, there were newspapers in Berlin with headlines: "Numerous armies rush to free Berlin from the blockade." Soon our units will find out what is the truth and what is a fiction.

Goebbels interrupted me, indignantly saying: “Are you giving me a reprimand?” I had to restrain myself to answer calmly: “As a commander of the troops, I consider it my duty to point to this danger.” Borman reassured Goebbels. This clash occurred in Hitler’s presence, however, he did not say a word.

At that moment, Reich Secretary Nauman burst into the office and, interrupting my report, announced with the great excitement: “My Führer, the Stockholm radio transmitter reported that Himmler made an offer to the British and Americans about Germany’s surrender, and received from them the answer that they would agree to negotiate if Russia will be included as a third party.” Silence reigned. Hitler pounded his three pencils on the table. His face twisted, fear was visible in his eyes. He said something to Goebbels, which resembled the word "traitor." For some time, the unpleasant silence continued, then Krebs, in a low voice, suggested that I can proceed with my report.

I continued. Both Berlin’s airfields, Tempelhof and Gatow, were lost. The alternate airfield built in the Thiergarten was only partially suitable for take-offs due to a large number of bombs and shells craters. The supply of Berlin became possible only from the air. Almost all large food warehouses, including the western port, on April 26 and 27 were captured by the enemy. We already experienced a lack of ammunition.

Since a few weeks ago in East Prussia I had to endure the defeat of an entire army in a small area, it was not difficult for me to paint a picture of the next few days. But this time the situation should have been even worse since the fate of the military units was to be shared by the civilian population. I painted the terrible fate of the wounded and read the letter of Professor Sauerbruch.

Before I was going to summarize the above, Hitler interrupted me: “I know where you are going to,” and came up with a long explanation of why Berlin needs to be defended until the last moment. His speech abounded with long pauses, during which Goebbels intervened several times, emphasizing what was said by Hitler.

Hitler's brief speech was as follows: “If Berlin falls into the hands of the enemy, the war will be lost. For this reason, I stay here and decisively reject any kind of surrender.” This time, I decided to not to vice an offer to leave encirclement by a breakthrough. Since it was already 2 am, they let us go. Hitler remained in his office with Goebbels and Borman.

All others sat down together in another room and began to discuss Himmler’s betrayal. At the end of the conversation, I spoke about the breakthrough plan from Berlin. Krebs showed great interest in this plan. He gave me the task to develop a plan for the breakthrough, and report back to him at the next meeting. His interest was so great that he asked me for a draft to make his comments.

The development of the breakthrough plan was conducted on the morning of April 28 at the Benderblock command post. The breakthrough was supposed to be accomplished in three waves from two sides over the Havel bridges south of Spandau. Hitler and his HQ were to participate in the third wave.

At noon, my chief of staff, Colonel von Dupfing, went to the Reich Chancellery and presented General Krebs with a draft. Krebs approved the plan. Meanwhile, the situation became even more complicated. The ring around Berlin was shrinking with every hour. At 22 o'clock on April 28, 1945, a discussion of the strategic situation took place again.

The number of listeners decreased. Hitler’s adjutants, Colonel von Below and Major Johannmeer were absent. Supposedly they were sent from Berlin with some important documents. I could not find out how and using what way they left Berlin. I cannot say with all certainty if I saw Gruppenführer Fegelein in the last group on April 28 or 29. I became aware of his execution on Hitler’s order only a few months later in Moscow.

This time, since there was a noticeable shortage of ammunition and supply to the city from the air was not sufficient, it was not difficult for me to proceed to the proposal for the breakthrough. Krebs took a positive stance on this issue.

Hitler pondered for a long time, then in a tired, hopeless voice said: “How can this breakthrough help? Do I need to be wandering around or wait for my end in a peasant’s hut or elsewhere? It is better in this case that I stay here."

Now it was all clear. It was about his personality, about his "I". In the same vein, Goebbels commented: "Of course, my Fuhrer, absolutely true!"

I expected everything, but not such an explanation. To be able to sit safely in a bomb shelter for as long as possible, many thousands of people on both sides had to make sacrifices on the front in this criminal struggle.

I left the Reich Chancellery in an angry mood. With rapid strides, the drama was nearing its end. The air supply on the night of April 28 to 29 yielded almost no results: only 6 tons of ammunition were brought in, among them 8–10 faustpatrons, 15–20 artillery shells and a small number of medical supplies.

The troops demanded the delivery of ammunition. Communications with individual defense sectors could only be carried out with the help of orderly officers who were supposed to travel on foot since there was no possibility of traveling by car in Berlin.

We in our command post found ourselves on the main defensive line. The enemy was on the other side of the Landwehr Canal. The Reichstag building was lost. Enemy’s fire was concentrated on Potsdamer Platz.

Running under the shelling and machine guns fire, I got to the Reich Chancellery in the mud. It was already 22 hours on April 29. Life in an underground bomb shelter was like a command post at the front. Those gathered in the office to discuss the situation were depressed. Hitler’s face sundered even more than before, he was staring blankly at the operational map in front of him.

I expressed the well-known maxim that even the bravest soldier cannot fight without ammunition. I insisted, to the extent possible, that Hitler would allow the start of a breakthrough. I ended my speech with the words: “A breakthrough will succeed if we meet a strike group.”

With bitter irony in his voice, Hitler declared: “Look at my operational map. Everything here is not based on information from its high command but based on the reports of the foreign transmitters. Nobody tells us anything. I can order anything, but any of my orders won’t be executed anymore.”

Krebs supported me in my efforts to get permission for the breakthrough, however, very carefully. Finally, the decision was made. With a further lack of air supply, troops can breakthrough in small groups, but with the proviso that all these groups must continue the struggle, wherever it will be possible. Surrender was out of the question.

If I could not get Hitler to stop the useless bloodshed, then at least I managed to persuade him to stop the resistance in Berlin.

Not a word was said about Hitler’s whereabouts during this breakthrough. I thought about it only when I arrived at my command post. However, taking care of his personality was not my responsibility.

At 10 am on April 30, following my order, all commanders of the defense sectors were summoned to Bandlerblock to get an explanation of what “small groups” meant and coordinate a breakthrough time. Since on the night of April 29-30, the supply from the air almost completely ceased, I set a breakthrough time at 10 pm on April 30.

All commanders agreed with my point of view that the military units under their command should remain under their control. We agreed that the concept of “small groups” should include those groups that were in the hands of their commanders. This was contrary to Hitler’s orders. However, there was no possibility to talk with Krebs from early in the morning, because all telephone communications were broken.

About 1 pm defense commanders were dismissed. They got moral relief because it was not necessary to conduct hopeless battles in Berlin. The future seemed not so bleak.

I intended to appear in the Reich Chancellery after dinner. At 3 pm a Sturmbannführer arrived (I don’t remember his last name). He had the task to hand me a letter from Hitler. Immediately, a thought flashed through my mind that I would be held accountable for violating the Führer’s order regarding the definition of “small groups”. My incredulous officers let the Sturmbannführer come in only when they took his weapon.

I opened the letter with an uneasy mind. It was dated April 30, 1945. Hitler repeated what was said at the last meeting, namely: “With a further lack of supply from the air, a breakthrough by small groups is permitted. These groups must continue to fight where the opportunity will present itself. Resolutely reject any surrender.” The letter was signed in pencil.

At about 5 pm I was going to go to the Reich Chancellery, as the Sturmbannführer reappeared. He was brought to me, and he conveyed a note with the following content: “General Weidling must immediately appear in the Reich Chancellery to see General Krebs. All activities envisaged for the evening of April 30 should be postponed.” Below it was written: "Sturmbannführer and Adjutant." The signature was unrecognizable.

I learned from the Sturmbannführer that the adjutant of Brigadeführer Monke had signed this note. Monke was the commander of the defense sector in the government quarter and reported directly to Hitler.

I found myself again facing a difficult decision. Is it all right? Or is this order a ploy of fanatical people who intend to fight in Berlin to the last bullet? Or was there any event that gave reason to envisage a completely different situation? After all, if I linger on for one more evening, then there will be only one possibility, capitulation. Given all of this, I decided to fulfill this order and go to the Reich Chancellery.

The Bandlerblock was less than a mile from the Reich Chancellery. Normally, this path required a quarter of an hour's walk, but now it took almost five times more. I had to make my way through the ruins, basements, and gardens. Almost all the way I had to jump from one shelter to another. When I reach Reich Chancellery at about 6 or 7 pm I was sweating heavily.

I was immediately taken to the Fuhrer's office. Goebbels, Borman, and Krebs were already sitting at the table. Upon my arrival, all three stood up. Krebs, in a solemn tone, stated the following: “1. Hitler committed suicide at 3 pm. 2. His death must remain secret. Only a very small circle of people knows about this. You, too, must commit to keeping this in secret. 3. Hitler's body, according to his last will, was doused with gasoline and burned in a shell crater on the territory of the Reich Chancellery. 4. In his will, Hitler appointed the following government: Reich President - Grand Admiral Doenitz, Reich Chancellor - Reich Minister Goebbels, Party Minister - Reichsleiter Bormann, Minister of Defense - Field Marshal Schörner, German Interior Minister - Seyss-Inquart. The remaining ministerial posts are currently not replaced since they do not matter. 5. Marshal Stalin was informed about this by radio transmission. 6. For about 2 hours already, an attempt has been made to contact the Russian command to request a cessation of hostilities in Berlin. In the case of success, the German government legalized by Hitler will appear on the scene, which will conduct negotiations with Russia on surrender. I will take a white flag bearer with me.”

The mood of those present and the business-like manner of the tone with which Krebs spoke were strange. I got the impression that all three were not touched by the death of Hitler, which until now was their god. It seemed to me that I was in the circle of trading managers who were consulting after the departure of their owner, and involuntarily said: “First I must sit down. Do any of you have a cigarette? Now we can smoke in this room.”

Goebbels pulled out a pack of English cigarettes and offered it to us. I took a few minutes to comprehend what Krebs said. My first thought was: “And we fought for this suicider for 5 years and a half. Having drawn us into this terrible misfortune, he chose the easier way out and provided us with our destiny. Now we need to end this madness as soon as possible.”

I asked Krebs: “You had been in Moscow for a long time and you should know the Russians better than anyone. Do you believe the Russians will opt for a truce negotiation? Tomorrow or the day after tomorrow Berlin will fall into their hands anyway, like a ripe apple. Russians know this, as we do. In my opinion, the Russians will only agree to an unconditional surrender. Should this senseless struggle continue?”

Goebbels answered instead of Krebs. In harsh words, he pointed out to me that it was necessary to reject all thoughts of the surrender of Berlin. "Hitler’s will is still mandatory for us."

Then, calming down, he stated the following: “The traitor Himmler unsuccessfully tried to negotiate with the British and the Americans. The Russians would rather agree to negotiate with a legal government than with a traitor. We may be able to conclude a separate peace with the Russians. It all depends on how soon this legalized government is formed, and for this, an armistice is necessary.”

I could only ask. “Mr. Reich Minister, do you think that Russia will enter into negotiations with the government in with you like the most ardent representative of National Socialism?”

When Goebbels, making an offended face expression, wanted to object, Krebs and Borman intervened in the conversation. Both began to convince me about the need to make every effort to conclude a separate peace with Russia.

My opinion that the negotiations can end only by unconditional surrender had not found any support.

As for Krebs, I felt that he internally agrees with me in many respects. For example, he asked me: "Can you name us a person with whom the Russians would agree to negotiate?" For some reason, I came up with the name of Professor Zaubruch.

Krebs did not dare to speak out his opinion, and he joined the other two to choose a truce option.

...

I was detained in the Reich Chancellery. I should have expected Krebs back. Waiting for Krebs, I managed to learn from Burgdorf and Bormann the details of Hitler’s last hours.

Hitler's fear of death has recently increased markedly. If, for example, a shell exploded close to his bunker, he ordered to find out as soon as possible if everything was OK. In general, the shelling caused him great irritation.

On the night of April 29-30, Hitler informed his staff about his decision to commit suicide. Mrs. Goebbels, allegedly, was kneeling in front of Hitler and asked him not to leave everyone in these difficult hours. Hitler poisoned himself and then shot himself. His wife, Eva Brown, also poisoned herself.

According to Hitler’s last will, the corpses must be burned. “I don’t want,” Hitler supposedly said, “my body being paraded in Moscow.”

Three SS put the corpses of Hitler and Eva Brown in the shell hole, doused it with gasoline and set them on fire. Since the corpses did not burn to ashes, after that they were covered with earth.

On the night of April 30 to May 1, 1945, I first learned that Hitler had lived with Eva Braun for 15 years. On April 28, Hitler married Eva Brown in the Reich Chancellery wearing Volkssturm uniform. With this marriage, Hitler wanted to legalize this fifteen-year cohabitation before his death.

I did not see Hitler’s will, and I did not manage to find out what was written in it. At 1:00 pm on May 1, General Krebs returned to the Reich Chancellery. The Russians, as was to be expected, rejected the truce offer, and demanded the unconditional surrender of Berlin.

My point of view again rested on Goebbels’s stubbornness, supported by both his devoted Borman and Krebs. The capitulation was rejected. I received permission for the breakthrough that I had previously scheduled for the evening of April 30th. I was released from the obligation to remain silent about the death of Hitler.

Meanwhile, as one would expect, [the situation - AWW] became so complicated that now it was impossible to even think about a breakthrough. On the night of May 1 and 2, I capitulated with the units with which I still had contact and surrendered to the Russian troops.

Being in captivity, I heard that Hitler's corpse was not found. This circumstance made me doubt whether Hitler’s death was not imaginary.

The events from April 30 to the evening of May 1 shocked me greatly, and I perceived the message about Hitler’s death as indisputable truth. At that time, the idea did not even occur to me that Hitler’s entourage could use my gullibility and deceive me. I believed that Hitler was dead, and therefore it was not by chance that I decided to say to Goebbels on the evening of April 30: “We will not be blamed in the future that we exactly fulfill the will of a suicider (that is, a categorical refusal to surrender).” Hitler left us in this terrible situation and therefore we have the right to act at our discretion!”

I hesitate to argue whether Hitler died or not, having only what I saw and heard. Turning to my memories about all the conversations with Hitler and the moments which connected me with his life in the last days, I ask myself a question, how can I support the notion that Hitler is still alive? And I answer this:

1. Hitler's fear of death and undisguised care about his "I."

2. Sending adjutants April 28 from Berlin. It was said that they were ordered the removal of important documents from Berlin. That much is clear. But they could also have a special assignment to prepare a place for Hitler’s planned escape. In this case, it is interesting, of course, to know which route and under whose escort both adjutants left the Reich Chancellery.

3. Business-like behavior, without a shadow of grief, of Hitler’s closest helpers, Krebs, Bormann, and Goebbels when they informed me that Hitler had died.

4. The obligation to preserve the secret of Hitler’s death, which was demanded from me. This, of course, could have been done due to military considerations in order not to cause concern in the ranks of the Berlin’s defenders. But it is quite possible that those who helped Hitler escape were interested in gaining time.

5. Many people lived in the numerous rooms of Hitler’s shelter. It is very difficult to imagine that the details of his suicide, the removal of the corpses from the shelter, and their burning in the garden could be kept secret.

After my captivity, I talked with the SS Gruppenführer Rattenhuber, the head of Hitler’s security, and with the adjutant of the SS troops Sturmbannführer Gunshe. Both said that they know nothing about the details of Hitler’s death. I can't believe it. Does the oath not bind all the initiates into this business?

Despite the arguments cited above, which caused me to doubt the veracity of the message about Hitler’s death; I still think that Hitler died. The motives for such a conclusion are as follows:

1. Hitler’s physical and mental state. Hitler was a mental and physical wreck. I cannot imagine that a person in such a state was able to move around ruined Berlin. True, one can argue that Hitler could have been helped and taken away. Opportunities to escape on the night of April 29 to 30 were still through the station of the Zoological Garden to the west and through the Friedrichstraße station to the north of the city. It was possible to partially go this way relatively safe using subway tracks. But at the same time, it is worth remembering that Hitler’s flight, despite the great conspiracy and in the presence of disorder in Germany, could not remain a secret to the public for a long time.

2. Hitler’s departure by plane from Berlin can be completely excluded. The reserve airfield in Tirgarten had not operated since midday on April 29. Since everything was covered with bomb and shell craters, even passenger cars could not pass. Theoretically, it would be possible to fly on an autogiro. I never heard that such an aircraft was available at the disposal of the Reich Chancellery. Besides, the landing or takeoff of this aircraft would not remain a secret.

3. If Hitler had considered a revival of Germany in the future, his thoughts on the new structure of Germany would not remain a secret from his closest associates. If this is assumed, it is difficult to understand why the most devoted people — Goebbels, Krebs, Burgdorf, and others — committed suicide themselves after Hitler's escape. After the truce negotiations failed, these people had to try to get out of Berlin.

Helmut Weidling

January 4, 1946

Wehrmacht General of Artillery Helmut Weidling leaving his bunker during the surrender of the Berlin’s garrison on May 2, 1945. (Frame from the documentary).

After the ceremony of signing the surrender of Berlin’s garrison. From left to right: unknown, General of Artillery Emil Vrubel, General of Artillery Helmut Weidling, Lieutenant-General Kurt Voytash, Colonel Hans Refior. May 2, 1945

German General Weidling and his staff officers after the capture.

Weidling's last prison photo, 1955.